| Issue #58 • July/August, 1999 |

A strident tone blasts me from sleep. I catch the words “fully involved” first time around. Where the heck are my glasses? Oh, God, I can’t find my glasses. Panic. Fumble the light on, knocking my specs to the floor. I’m getting too old for this middle-of-the-night stuff. The dispatcher’s monotone repeats itself and this time I get the details of what and where. I yank on yesterday’s clothes, always left by the side of the bed.

I hate structure fires. Hot dirty things that gobble up someone’s memories and dreams. Sometimes the people themselves. The really bad times.

A hurried stop in the bathroomlast chance I’ll get for five or six hoursand I pound down the stairs, finger combing my hair. The rest of the house sleeps on and only the dog raises one bleary eyelid at me as I tromp through the kitchen throwing on lights and grabbing keys.

The car fails to start on the first crank. Calm down, you’re racing like a rookie. I sit back in the seat, force the adrenaline rush down, and try again. This time the engine catches. I reach out and jab the plug for the red light into the empty cigarette lighter socket, snap the seat belt, and slam into reverse.

A mile from the scene the smoke becomes visible. There’s horrible beauty in a house afire. On clear cold nights the smoke rises straight up in a broad multi-hued column. Pink, gold, even green swirls through the black and gray. A palette devised by a schizophrenic artist intent upon painting his worst nightmares. Something Stephen King would dream up.

Damn! Damn! Hell! Definitely hell. I realize I’m slamming my fist against the steering wheel and stop. This one’s a real cooker. Flames, visible even above the trees, lick at the smoke, chasing it higher. No water flowing yet either. Not if I can see flames from here.

You can tell if the others who got there before you have started knocking down a fire because the color washes out of smoke as water turns to steam.

Thick oily black smoke roiling up is always a bad sign. Means something nasty is burning. Burning fast and hot. Hydrocarbons. Hazardous materials. Something other than good clean wood. Not much wood in houses any more. Synthetic materials that give off toxic gases when they burn. Gases that kill firefighters.

I experience the heat, so intense it stabs through the closed car as I drive past looking for a place to park. Can’t see a thing. Fire’s too bright and the darkness too dark. Afraid I’ll pull into a ditch and become another casualty the others have to deal with.

I haul off my shoes and coat, struggling into bulky gear and rubber boots designed more for protection than movement. A final grab at helmet and gloves and I clump off in search of my captain and instructions.

The fire ground is like a scene from Faust. Shadows dancing in the reflected flames are brought to stark life by the sudden flare of halogen lamps abruptly lit. Figures scamper to-and-fro between trucks and burning building. Uncharged hoses snake everywhere in the tumult. The noise is painful. Officers shout orders to the troops amid the crackle of portable radios and ravening flames. Engines grind to a deafening roar as the pumps engage. To an observer it would appear as chaos gone mad; but there’s an order here, known only to the participants.

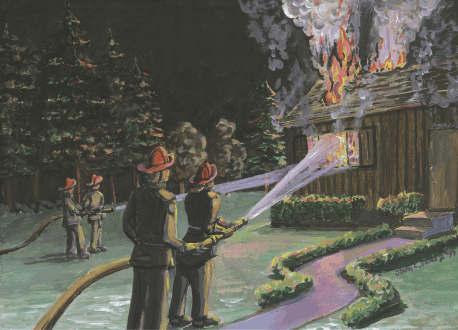

Not much of a crew here yet so the captain puts me on a hoseline with another veteran of these sad wars. There won’t be any interior attack on this one. We can’t get near the inferno to get inside. Hose clamped to my hip, I struggle to keep standing as dirty black water runs over the ice underfoot. Back and forth, back and forth we aim the stream of water, a hundred pounds of pressure’s worth, at the gorging enemy. He runs his greedy fingers up walls and licks a slavering tongue through the holes he’s chewed. A window explodes from heat and pressure and we duck the flying shards.

A fire uses up oxygen at an alarming rate, replacing itself with toxic gases and smoke. These gases become superheated increasing the pressure inside the building. Eventually this pressure will blow out windows or doors and the renewed burst of oxygen will ignite the fire with explosive results. A house in backdraft readiness will puff smoke in and out through any available cracks around windows and doors, a sure clue to trained firefighters that death awaits the unwary.

A house on fire roars like a demented hurricane, a howling rumble interspersed with the cackle of sparks and the hiss of steam. At first the heat, a thousand degrees and more, drives us back, but we slowly knock the enemy down, our puny stream spitting in the face of the blaze.

The hose abruptly goes limp and the fire jumps up in glee to gobble a door and waggle his tongue at us. We shout and gesture though, knowing our comrades back at the pumper are scrambling to get the water flowing again. We’ve been there at fires past, aware of the unavoidable glitches. We bitch anyway, venting our frustration while the fire regains his lost ground.

The hose surges to life, nearly knocking me down, and we resume the monotonous back and forth stream of watery bullets. We tango forward and back with the fire for what seems like hours and probably is. First he advances, and then we bend him backward over the bulk of the devastated house. Eventually, the captain raps me on the helmet to get my attention and hand signals to shut down our hose.

Hot and sweaty, our faces grayed with soot, we trudge towards the ladies’ auxiliary for sandwiches and a drink. Coffee? Water? Gatorade or soda? I gratefully accept a diet soda and pull open my coat. Steam rushes off my chest, my own perspiration turned to vapor by the heat.

The auxiliary ladies look at me and shake their heads. They’ll never understand why I want to be on my side and not theirs. All they see is a woman, no longer young, who opts for the grinding dirty drudgery of firefighting. They’d rather minister to the fighters than the fire and can’t comprehend that I do it because I’m terrified of fire. I need to do battle with it. A few have asked me and my answer confuses them.

I rub my arm across my face, smearing the grime. I know I look a mess, hair never properly combed now flattened by my helmet. I’m too tired to care. I sink down onto the cold back step of the rescue truck, knowing the job is only half done.

Exhausted firefighters don breathing apparatus and venture into the ruined house. On a search and destroy mission, they tear down any remaining inside walls where the enemy may still be hiding and waiting for his chance to continue the rampage. Too old to be allowed to do inside work, I switch from firefighter to EMT.

I help refill air bottles as my fellows stagger from the building, dirtier still, alarm bells ringing a few minute’s worth of air left in their tanks. I check them for heat exhaustion and smoke inhalation. They test positive when the whites of bloodshot eyes go gray and flushed skin feels dry. If they pass I load them up with a fresh bottle and send them back.

Most firefighters have to be restrained from returning to a burning building too many times. The mix of adrenaline, oxygen deprivation, and exhaustion blurs common sense and breeds madness. The EMT staff is there to make sure this idiocy doesn’t result in tragedy. One reason most senior officers don’t fight fires is that someone needs to keep a clear head.

A shrill shout. Firefighter down. A beam has fallen on someone. They’ve got to get him out before his air supply is gone. I stand by the rescue truck, twitching nervously, going over in my mind what I’ll need off the truck. I grab a shell-shocked compatriot and pile him up with splints and a backboard. Given a purpose he pulls out of the hole he retreated into and follows me toward the building.

I meet another EMT as he emerges from the wreckage. Wordlessly he grabs the backboard and charges back inside. Soon they all come out with our fallen comrade. He moans and tosses on the hard narrow board, trying to tear his facemask off. I reach down and gently remove it for him. His air pack has already been taken off and, still attached to the mask, is carried beside him.

I try to calm the man I’ve known and worked beside for years while I run my hands all over him feeling for broken bones and deformities. He winces a couple of times, complains of back pain and sore knees, and begins to breathe more normally. The heavy timber hit his air pack, knocking him to the floor and pinning him there. He’s lucky,

The ambulance picks its way through the covey of fire trucks and I reluctantly turn my friend over to the paramedics outlining his possible injuries. They immediately start an IV and check him all over once more. I find their arrogance vaguely insulting, and watch helplessly as they speed off with the firefighter on board.

Fire finally out, weary and running on fumes, we pack up hose and air bottles and shut down the lights. Back at the station we’ve got three or four more hours of toil ahead of us. Filthy hoses have to be washed down and hung to dry. Clean hose must be loaded onto empty trucks in case, God forbid, we should have another fire somewhere soon. The self-contained breathing apparatus has to be put back in service, filling air bottles yet again and disinfecting masks.

We drag along on leaded feet until the chores are at last finished and we can drive home to shower and fall in bed. Or head out again to work, stale and stupid, unready for whatever the day demands.

The reasons why brave and foolish souls voluntarily rush into burning buildings are obscure. To prove we’re still alive? The addictive adrenaline rush? A gigantic desire to do good in the community? A monumental hubris that shouts “invincible?” If you asked us “why?” most couldn’t give you an answer. Nothing that makes sense to anyone, including ourselves. The explanation’s too complex, too personal, too visceral for those who haven’t done it to understand, and the rest of us don’t need to.