| Issue #147 • May/June, 2014 |

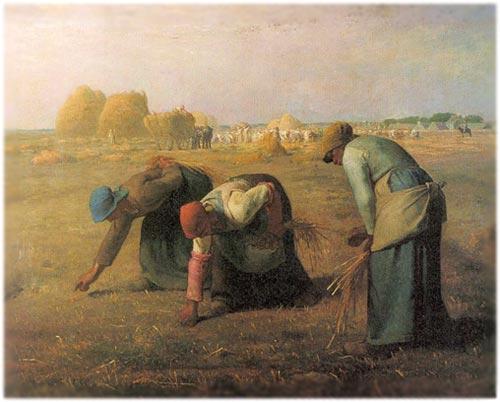

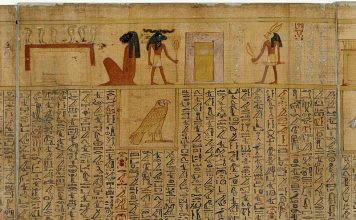

Gleaning. You may remember the term from Sunday School or your Bible studies. In the book of Ruth, “gleaning” refers to poor people being allowed to follow a landowner’s regular crop pickers, taking the leftover grain or other produce for themselves and their families.

The tradition is still alive, if not exactly common, these days. In its modern incarnation, it involves stocking food banks, soup kitchens, and churches, and earning tax breaks for farmers. It’s also a great way to build up your own larder at little cost.

My family and I have been involved in three gleaning associations in northern Idaho and have developed farm and orchard contacts in our region and the agricultural areas of central Washington. These farmers and orchardists are either willing to donate large quantities of fruit and vegetables that they’ve harvested or they allow our group to come onto their property to pick the remaining crop. We set up our current association through the state and are recognized by the IRS as a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization.

We have chosen to glean in a highly organized way. Individuals who live near farming communities can certainly arrange to do some gleaning on their own with fewer formalities. A couple of families in our group did this regularly in the area where they used to live. However, there are difficulties in “going it alone.” It’s very labor intensive to scout the farms and do the gleaning, and even if you plan to share part of your harvest with the needy, as an independent individual you probably aren’t in a position to give the landowner paperwork he can use to claim a charitable contribution on tax day. Most farmers don’t mind if a single family gleans as long as the gleaner explains that it’s for personal use and that they will not resell the product, but some may refuse permission because they’re wary of possible liability should you be injured on their property. An association, on the other hand, can offer a receipt for tax deduction and a pre-signed waiver of liability.

Besides, it’s more enjoyable (and more productive) to glean as a group.

A group shot on a cherry glean where it rained and everybody got wet.

The process is fairly simple and the benefits can be substantial. Last year our group of 25 families (primarily retirement age) gleaned several thousand pounds of cherries, peaches, potatoes, and apples, as well as hundreds of pounds of corn, squash, peppers, and other vegetables. We were also given more than 7,000 pounds of onions, 5,000 pounds of apples, 1,500 pounds of asparagus, and 2,500 pounds of potatoes.

The primary reason for our success is that we are able to give each landowner a donation receipt and show the grower a copy of our liability waiver, which every gleaner signs prior to entering the field to glean. We also provide the landowner an information sheet that shows the 15 regional food banks and other recipients we support. The information sheet describes the advantages of donating to us and includes the names and phone numbers of our association’s board members in case anyone has further questions.

One of our group’s rules is that we have to give at least 50 percent of the food to food banks or directly to needy people. More specifically, we require that 25 percent go to one or more organizations on our approved list of recipients, while another 25 may go to friends, neighbors, or other individuals we know are in need. Individual gleaners are in charge of the food they personally pick or receive; we require them to get receipts (which we check) to ensure that they are giving away at least 50 percent. The only exception to this rule is if a glean yields less than 50 pounds; in that case a family can keep all it has gathered from that glean.

In most cases, gleaning families end up giving much more than 50 percent. For example, over the past two years, my family has gleaned more than 1,000 pounds of potatoes and apples annually. Even if we juice and dry and can, we usually give most of it away because it’s so much more than we need.

It is also absolutely against association rules to sell any product we gleaned or that was donated to us. In that way, we keep to the Biblical tradition: what is gleaned is for the use of the gleaners and the poor.

However, because of our very large existing contact base, we are able to purchase dry, processed beans, rice, corn, oats, and other items at wholesale prices from four large processing plants in central Washington. Each summer we also purchase apricots, peaches, nectarines, pears, and apples. These we do re-sell, both to members of our association and non-members. Several of the regional food banks that we donate gleanings to also order these items, as they aren’t able to purchase similar products at the low prices we offer.

I say, “we,” but it’s actually me and other group members doing this buying and selling, as individuals. In fact, it’s very important for any potential gleaning organizations to note this: The IRS would frown on using association funds to purchase commodities or produce for sale. So when we buy goods to raise money for our gleaning, we never use association funds. Buyers (both association members and the general public) pre-order by writing checks to me personally. I cash the checks prior to making a particular purchase. Then all profits (minus fuel costs and the cost to buy the goods) are donated to the association. It is a completely separate operation. We simply use it as a way to raise money for our charitable work.

We use my truck and trailer — it’s usually full once we leave. This allows others to drive fuel-efficient vehicles to the gleaning location.

Getting started

It’s probably best to start organizing in the spring because you’re going to need time to make contacts before the harvest.

There can be a “which came first, the chicken or the egg?” problem when starting a gleaning association. To persuade landowners, you need to have members and food banks or other organizations that have signed on to receive harvest bounty. To attract members and organizations, it helps if you’ve already persuaded at least a few farmers. You can help overcome this problem by working both sides of the issue at once. Interest a few friends and one or two food banks, then with that background, approach a few growers. Once a handful of growers have committed, you can draw in more member families and have more to offer food banks. (You can see how it helps to have more than one individual or family working on the project.)

You might also want to make presentations to church groups (our association is open to all who want to join and have the time to participate in the gleans; its members include people from various churches, including Mormon, Lutheran, and Seventh-Day Adventist, as well as unaffiliated individuals). Preparedness groups, patriot groups, and Oath Keepers (retired military and police) gatherings are also good places to recruit members, as these people foresee a perilous future in which we may experience food shortages and even food riots. Food security is important to them and gleaning can play a role in that.

Because we had prior experience organizing a gleaning group, we were able to jump in with both feet. We called several friends and neighbors and developed initial interest. Then I drafted a letter to the editor of our local newspaper announcing that we were forming a regional gleaning association and rented the local community hall for a meeting. At the meeting we distributed the planned bylaws and reviewed our plans to start what we named the Pend Oreille Gleaners Association. We also elected a board. I was chosen president.

Since we had been members in other groups, we already had a list of some of the gleaner-friendly farmers in the area. But we immediately decided that we also needed to drive through the region and develop additional glean locations and create an informational sheet. We also needed to make new contacts with the food banks and other organizations that would receive a share of our harvests.

At first, we wasted quite a bit of time explaining our purpose to two different food banks. At that point, we did not have our own tax-exempt status and were seeking to operate under the sponsorship of an organization that did. The first food bank we approached was a large organization with several subsidiary food banks under its corporate wing. They declined us because they’d recently had a bad experience with another gleaner group. The second food bank we approached was interested in officially sponsoring our operation, but we learned that their IRS status did not permit them to support multiple groups (that is, their own plus ours).

We finally learned that food banks would have to upgrade their IRS status to allow multiple support groups before they could sponsor us. That meant not only more paperwork for them, but a significant amount of additional money ($3,000 or so, if I recall correctly; in any case, a substantial sum for either the food bank or us). I found out that many other gleaner groups were really “under the radar” and probably not recognized by the IRS. (We learned through hearsay that one of the groups did go through quite an IRS audit and had several problems.)

That’s when we realized we should have our own tax-exempt status. I discovered that our local bank needed us to send the State of Idaho our bylaws and a list of the officers of the group. The state would then assign us a non-profit association number. With that we would contact the IRS. The IRS would assign us an employer identification number (EIN), which the bank needed to set up our checking account. Complicated, but just a one-time process.

We were able to accomplish all this in three days with the bank’s help. Since then, we file our tax report online, with a very simple, yes/no questionnaire that takes about 15 minutes to complete. A couple things have made our association more desirable to members than some similar groups. First, we meet as a group only once a year. Other gleaner groups we’re aware of meet monthly. Second, the other groups have to do yard sales, coffee sales at rest stops, or other labor-intensive activities to get donations. We have developed a large group of interested citizens who enjoy fruit and vegetables during the season as well as purchasing dry-good commodities. So we’re able to fund ourselves with activities that are directly related to the purpose of our organization.

Loading some pumpkins and winter squash in our truck

Making farm contacts

When you’re ready to begin scouting locations for gleaning, drive into the growing region nearest you. If you’re not sure where to start making contacts, try the county Farm Bureaus, which usually meet once a month and are full of information on where and when crops are harvested and who the owners are. Making contacts at local grange halls or perhaps your local university extension office can also be useful.

Sometimes you have to be persistent to find the right person to talk with. Locating the owner or manager of a large operation can be a challenge. (Some gleaner groups stick to harvesting from small farms and orchards; we’ve specialized in developing contacts at larger farms, which are often owned by corporations.)

If you are in the midst of a large growing area, you may be able to make multiple short scouting trips. Because our prime gleaning territory is at a distance, we usually plan two or three all-day trips. We depart from home around 4:00 or 5:00 a.m. to be in the growing area by 8:00 a.m. When our group’s VP and I canvas a region, we spend all day talking to various farmers, sometimes driving to Yakima to visit corporate offices. That’s about 4½ hours one way (about 250 miles).

Having found the person who has the authority to make the decision, you now most likely have some explaining to do. This is why we have a pre-printed information sheet that explains who we are, our purpose, and the communities we support.

Most landowners or managers don’t want to take the time to talk with gleaners because they’re busy. Then, many landowning corporations have lawyers who have researched the issue; they simply don’t want to open themselves up to liability. We cover this issue with our liability waver which we require each gleaner (even children) to sign before we enter a field. Attorneys for some orchards have said we have to provide a certain amount of accident insurance. We aren’t able to do this so on we go to the next farm.

Soon we have a solid list of contacts, the crops they grow, and the approximate dates of their harvests. Now we wait for the ripening.

This is a picture of our grandkids, Tasha and Christa Joy, picking apples.

Gleaning the fields

One advantage to a gleaning association is that members don’t all have to be from the same area. Our group is based in Northern Idaho, where my wife and I live. But we have members as far away as Hermiston, Oregon. Many of our gleans are in Central Washington, so in many cases, essentially everyone participating is traveling to a central point.

Not every member participates in every glean. We require every member to do at least two in a season. Some gleans may be too far away for some members. However, the more gleans a member family participates in, the more food, and greater variety of food, for them, their neighbors, and the food banks in their area.

Keeping track of the harvests is another matter. In our group, that’s one of my jobs. I have a notebook, which I try to update yearly with the contacts and crops. I also list the various crops in order of harvest. When I make a good contact, I list the crops that location grows and when their harvests are.

Shortly before a harvest is due, I usually contact a grower from our list and ask if there is a possibility of gleaning their specific fruit or vegetable that season. When I obtain permission, I usually drive to the farm or orchard to see how much is available and learn if there are any restrictions on the number of gleaners or if the farmer has any other concerns. In many cases, we will be meeting a company’s foreman, who will show us the specific area to be gleaned.

I then call one of our board members, who in turn calls the membership. If the property owner allows only a limited number of gleaners, we start on the first page of our membership and systematically call until that number has agreed to participate. The glean is often conducted the following day or two, so in many cases, some members are unavailable.

My wife, Christine Furtney, gleaning corn in the fall of 2013

We next agree to meet at a local grocery store parking lot. We usually assemble early in the morning and carpool to the gleaning site in the most fuel-efficient vehicles. Sometimes, one participant will drive a big pickup, perhaps with a trailer, while the rest follow in less gas-hogging cars. The truck, of course, will then haul the bulk of the gleaning.

Members who live in distant locations (for us, that means southwestern Washington and western Oregon) may coordinate a separate meeting location and caravan route. Somewhere along the route, we take a rest stop, and that’s where we have all participants sign their liability waivers. At the glean site, I meet again with the foreman unless we’ve prearranged otherwise.

Before beginning to glean, I review any concerns about picking the crop. For example cherries grow from small, delicate nodules. If those are picked off, the tree will not produce on that nodule again the following year, so I make sure that every gleaner knows how to avoid damaging such fragile structures.

We then choose individual rows of the orchard or farm and begin picking, using our own equipment. We bring bags for potatoes, banana boxes for apple picking, or hard-sided cardboard boxes (from the peaches, apricots, and other crops we purchased the previous year). We usually pick for two to four hours, depending on the heat, fruit condition, and other factors.

At the end, we gather to weigh each gleaner’s picking. We bring a small portable digital scale to record the amount each family picked. At that time, I try to remind the gleaners that they will need to show receipts after they give away 50 percent of each crop picked. We hand out pre-printed receipt forms to make that job easier for everybody. Members usually have about 30 days to return their receipts to us (we have occasionally had to eject a family from membership for failing to send in those receipts).

After the glean, we head home, tired but satisfied. But our job still isn’t done! After returning to our parking areas and dispersing, we make arrangements and deliver fruits and vegetables to our recipient organizations and families. Then we head into our own kitchens for freezing, canning, drying, and otherwise preserving our own share.

We transport as many as 600 to 700 lugs (20-24# fruit boxes) at some times during the season, including both the gleanings and the items we buy wholesale and sell to raise funds. Last year we had mechanical problems with our vehicles one day. By the time we got to the church parking lot to deliver, it was 10:00 p.m. and more than 80 families were waiting to pick up orders. It was quite a long day. But many people even gave extra donations for being able to get fresh, reasonable fruit.

My wife pouring a bucket of Rainier cherries into the boxes that we will haul back. We use old fruit lugs that stack nicely without damaging fruit.

Enjoying the harvest

Most food banks really enjoy being able to distribute fresh fruit and vegetables. Canned and prepackaged foods are easier for them, which is why many seem not to have much produce. But they enjoy fresh and gladly give us a signed receipt for the pounds of product.

Of course, our members get to enjoy some of the fruits of their labors for themselves. This may be one reason we have a long list of families waiting to join us.

Gleaning groups tend to remain small and keep a low profile. If there are too many in an area or more gleaners than the harvest can justify, farms that give permission may be overrun with too many requests. We have unfortunately had certain good farms stop all gleaning for that reason. So here’s a hint: don’t share your gleaning locations with other gleaning groups, and beware of members who may leave to start associations of their own and “poach” your contacts.

But what if you just want to join a gleaning group, not organize one? For that, you may have to keep your eyes open and count on word-of-mouth or the occasional notice in a local paper or on a bulletin board. All the groups we’ve been part of were private groups of like-minded individuals who want to supplement their own food stores while helping others. To the best of my knowledge, there is no central database of gleaning groups and most don’t have websites or other readily-available contact information.

If you’re interested, though, it’s worth the effort to find or start your own gleaning group. There’s tremendous satisfaction in bringing home hundreds of pounds of fresh food and knowing you’re helping others as well as your own family.

I will be happy to share our Pend Orielle Gleaners Association paperwork and organizing materials (but not our farm contact lists!) with anyone who’s interested in starting a gleaning group. Contact me at d.cfurtney[at]yahoo.com.

This website has not been updated in many years, but it still very useful. https://fallingfruit.org/ Always ask before you pick if it is on private property in case a new owner has moved in and does not want you on the property. Also, since some sources may no longer be available or current, try to stay close to home so you do not waste time and gas. I always travel with extra cardboard picking boxes in my trunk, never knowing where I might find free food, even wild foods. Go for a walk through the same wilderness area at least once every season to notice how the landscape and vegetation changes. You should have a route where you walk several miles regularly–whether walking a dog, hiking or walking to work or shopping, etc. You see a lot more on foot. Also, watch craigslist free, esp. in summer, for people who have garden explosion. Keep a contact list from where you picked previous years and a calendar so you can check back with the same people in-season, at the same time, the following year. Know wild food sources in your area–contact Fish and Wildlife and national/state/city parks. Learn to recognize wild mushrooms, berries, herbs, greens and nut trees. Contact your county extension, garden groups and librarians (newspapers articles) and food banks to find free seed swaps. Follow the seasons and harvest when food is available–plan ahead! Know your heirloom seed varieties and save your own seed from supermarket products such as squash or when buying beans from bulk bins as seed. You should not need to buy much new seed every year! Research how many growing days each variety needs, too. Anyone with land under their feet and a running vehicle in reasonably decent health should be able to feed themselves. We have even done so during years when we lived in an apartment and had only a patio garden, but we gleaned, foraged, hunted and fished. Children should also be taught basic skills and how to work. There is a saying–“A boy who knows how to plant and dig potatoes will never go hungry.” This implies that a child has been taught to grow food and knows how to work.

Too bad there isnt something like this around here. We have a farm that sells various veggies at stands. Alot of pumpkins, squash amd other things stay in the field due to imperfections. Such a waste.