| Issue #50 • March/April, 1998 |

Near the top of North America’s wildlife food chain is the mountain lion, a close second to bears in various forms in ferocity, strength, and killing ability. In recent years, the wild felines, also known variously as panthers, pumas, cougars, catmounts (cat of the mountains), and big cat, increasingly have become entangled with every animal’s worst enemyman.

Human populations relentlessly encroach on the lions’ domains while laws protecting them or regulating their depredation have increased the lion population as well.

Fortunately, tragic lion/human encounters still are rare but of the 50 recorded attacks in the past 100 years, most of the attacks have occurred in the most recent 20 years.

The rare events hardly are sufficient to generate any sort of public panic but the statistics do reflect an exponential rise in such encounters that, with current laws and human sprawl, has no chance of abating.

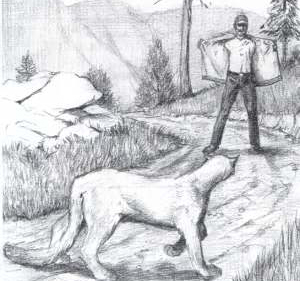

Anything that makes you look bigger, including opening your jacket up wide, may confuse a lion enough to deter an attack.

The cats are widespread throughout the United States, and in some cases the populations are calculated at all-time highs. Montana, as a typical mountain lion habitat state, is about half mountains (hence the corrupted Spanish name for “Mountain”) and the remainder hilly uneven plains. The western third of the state, the entire southern tier, and isolated mountain ranges in the central part of the state, are all considered mountain lion habitat. The huge Fort Peck reservoir periphery in the northeast quadrant of the state also is major cat territory.

The big felines traditionally have restricted their areas to the good cover such forests provide, but as the human and cat populations vie for similar traditional habitat, the cougars are likely to be found in less traditional locations. Their presence in plains and valleys may be only transient but also may be the result of human-provided food such as livestock and pets. The chance of meeting, or worse, tangling, with a mountain lion is unlikely, being slimmest in a state like Montana, which is nearly the size of California but with only a fraction of the people California supports. However, lion/human encounters aren’t limited to the sparsely populated areas.

Certainly an individual living in the cat’s natural habitat runs a stronger risk of puma problems than one in a big city. However, a recent scare in a Los Angeles suburb indicates that the animals are either desperate for sustenance or may be losing some of their fear of humans.

Both California and the Big Sky Country, as well as other states, have issued informational brochures on living with the cats.

California long has been blessed or cursed with a growing human population. The growth is the result of the state’s voters’ preference for a full protection and preservation policy that assures not only the cat’s survival but that its continued numbers increase.

Montana’s recent growth is a microcosm of California, as the big border state undergoes some rapid development and population increases. Both states’ wildlife agencies are concerned about the potential for more reported lion-man clashes.

While California treats the mountain lion as an endangered species, subject to control only in the most unusual and threatening situations, Montana treats the lions as a game animal subject to hunting in a regulated season. But this is a far less open policy than the bounty system once in place in Montanaand in California as well.

Both policies tend to enhance the big cat’s population figures. A female may first breed from eighteen months to two years of age, bearing from one to five kits. These youngsters stay with the mother until another litter is produced about two years later.

As lions live in the wild an average of 12 years, the statistical production of one female may range from six to thirty additions to the lion population during the course of her life.

Naturally, there is a loss to bears and accidents, while automobiles take a toll of lion life on the highways. In spite of some contrary information, lions are not characteristically subject to disease and do not spread disease.

Captive lions can live as long as 25 years, according to the California Department of Fish & Game, and they estimate that California’s lion population grew from 2,400 in 1972 to more than 6,000 in 1989, the last cat census year, and the state admits the lion population probably has grown since then.

With the knowledge that the big cats probably will continue to thrive and increase in numbers, those who run the risk of encounters should be aware of some life-saving or at least risk-reducing facts about the cats.

Information about lion attack survival has been compiled and developed into a group of lion encounter hints. It should be noted that no agency is attempting to discourage visits or permanent residency in lion territory. Most undeveloped areas, particularly the mountains, are inherently dangerous to humans. Without proper caution that danger can manifest itself.

Snakes, insects, falling rock, disorientation, rushing water, and all the other natural characteristics of the wild and semi-wild can be hazardous for those who venture into them. Even such organized activities as skiing can be fatal, as a couple of recent celebrity deaths show.

Coupled with the restricted access to help and medical aid, the wilds regularly take a human toll. Mountain lions, while part of the perils, probably are among the last things about which a backwoods denizen must be concerned. More people have died on the slopes of northern California’s Mt. Shasta in hiking and other activities in the past two years than have been killed by cats throughout the entire state in its recorded history.

The operating word in a lion encounter is “unpredictability.” The animal may intimidate, run, or attack but no particular cat action should be assumed.

The paramount protective element in an unavoidable lion encounter is man’s characteristic upright stance. Cats consider almost anything on four legs as fair game, but the vision of an unnaturally erect animal results in some confusion on the part of the beast.

A child, however, with a small stature may appear as a small animal to a lion. During the last 20 years, 70 percent of the cat attacks were perpetrated on children and in recent years, that figure has climbed to 90 percent.

If a child is present in a lion encounter, the child should be picked up by an adult, although the adult should bend at the knees in the lifting effort to maintain the erect position. The lion may associate a crouching or squatting human as natural prey.

It’s also important to enhance the upright position by appearing as large as possible. Spreading the arms and standing on tip-toe are protective maneuvers which can be exaggerated by a spread coat.

A calm, soothing voice directed at the cat may create more confusion or even fear in the lion.

If conflict is unavoidable, the primary recommendation is the strong admonition to “Fight Back! Never run!”

In the absence of more positive protection, such as a firearm, a number of natural tools such as a large stick or rocks may add a measure of protection. However, obtaining these “weapons” from the ground should be accomplished without bending over and as quickly as possible.

Both states report instances in which rocks and sticks, even fishing rods and fists, have prevented serious injury or death in lion conflicts.

Only a bear or a larger lion will intimidate a puma. A dog is of no protective value, in the traditional sense, against a big cat.

The dog’s presence may be a problem or an advantage, depending on the fickle cat’s aggressive decision, in that the dog could attract a lion to human habitat as potential, and ultimately real, food. At the same time, the dog also could be a sacrificial diversion away from the human.

The wildlife agencies empahsize avoiding any effort to run from a lion. That can trigger an instinct to chase prey, regardless of the number of panicky legs that prey uses, and this is an animal that can run down a deer or elk. Escape by running is impossible.

In all cases, one should constantly face the animal. Retreating, without turning one’s back, will not necessarily indicate an element of human fear and will give the lion reassurance that it isn’t going to be cornered. A lack of escape access for a lion almost assuredly will precipitate an attack.

A covered carcass of a deer, elk, or obvious lion prey means the lion intends to return later to eat on a kill. It’s the lion’s nature to protect its food source, and approaching or staying in the area of this food stands a good chance of a headlong clash with a lion.

Females are likely to be with cubs and the youngsters may stay with the mother as long as two years. Another litter may be on the way soon after the juveniles are weaned. As any other mother, they will protect the cubs with aggressive behavior of the most serious level.

Avoiding the cats is the primary safety measure. While it remains the best option, it is a declining one as the habitat line between cats and man increasingly narrows.

The mountain lion’s ideal habitat is abundant cover and adequate food, notably deer and related animals. That also describes the habitat of many who read this magazine, but those self-sufficient individuals don’t have a corner on the lion encounter market.

Even those in all but the inner city are increasingly encountering the animals.

It should be remembered that the animals are solitary, with the exception of juvenile or subadult litter mates and their mother.

Each lion tends to claim from 50 to 150 square miles of personal territory. Consequently, if one adult cat is seen or encountered, it isn’t likely a second adult or subadult will be anywhere near.

The presence of deer almost without exception means lion territory. It is unlikely one will run across a special lion territory marker, consisting of piled up dirt and forest litter spiked with urine or dung. These are called “scrapes” and all lions respect these territorial claim markers. To a human, it is positive indication that a lion is somewhere in the area and the human likewise should respect the territory and at least be aware of a potential encounter.

The most likely lion encounter will involve one, and infrequently two, juveniles or subadults who have been weaned from the mother. These young lions have no personal territory initially and are seeking unclaimed ground. They are the most hungry for food and are more likely to take a chance in checking out human habitat.

Nearly all the recent semi-urban sightings have involved young weaners. The litter mates will not stay together long as the lion adults unite only for breeding. These young animals, although smaller than the adults, should be avoided the same as large adults.

A veterinarian once told this writer, “A determined house cat can rip you to shreds and there’s no way you can retaliate in time to prevent serious injury.”

It’s safe to assume that if a 10-pound tabby can do major damage, a 50-pound “cub” mathematically can do five times the harm.

A full-grown 100-pound female lion can take down a 400-pound elk, said Montana officials. For deer, the usual killing method is biting just below the skull at the back of the neck. But the lion often may kill an elk by pulling back the head and breaking the neck, which demonstrates the physical power of the lion.

“The mountain lion is inseparably tied to deer and elk as prey species,” said the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks. But even in the absence of deer family members, there is no assurance that cougars are equally absent. The Montana agency points out that the cats also prey on small rodents and birds, and even the well-protected porcupine is fair game for a lion.

It must be emphasized again that the chance of sighting a lion is remote and a real confrontation is even less likely to occur.

Lion encounters are probably as rare as jet liner crashes, but, they rate major news coverage. However, unlike the high-flying tragedies which one would hope diminishes, lion/human encounters are almost certain to increase.

Under California’s lion preservation agreement, the state was supposed to encumber $30 million a year for 30 years as lion haibat land purchase. The idea was to restablished state-owned habitat to prevent any human development in the prescribed areas. So far only a fraction of the funding has been spent for lion land and what has been purchased is less land than one lion naturally requires.

No one should be afraid of the woods, whether traveling or living in that environment, for any reason, and least of all because of coungars.

Avoiding cougars is simply a matter of reasonable caution and common sense while following the guidelines provided by the wildlife agencies.The flip side of the lion issue is seeing one from a safe distance or position. Some people have spent much of their lives in the wilds without ever seeing a mountain lion. From a safe vantage point, the viewer is blessed with one of the most beautiful sights the animal kingdom can offer.

I recall living in Montana where we had a cougar living near the creek below our house for quite a while. When we would hear a cat shriek after dark, we knew he had found his dinner. It was earie. I simply did not go out after dark–at least no further than a well-lighted front porch or to a nearby truck.

The biggest cougar I ever saw was in the mountains of MT. If I had been at a zoo, instead, it would have looked the same to me as a full-grown African lion!

My husband and I were out hunting elk one winter day and were fortunate we decided to turn around and head home when we observed that a blizzard was moving in. Prints in the snow not far behind us showed we were being tracked by a grizzly bear… not far behind were cougar tracks. There may have been elk there, but I refused to hunt the area again. (Another time, we heard a grizzly bear snuffling in the bushes as we were packing out a moose just before dusk. That made me wonder about the sanity of “trailing for griz” with a bloody moose carcass! But, you get meat when and where you find it.)

Being armed is not always enough as cougars will attack by surprise and move very fast when they do. Fortunately, they prefer to avoid people–most of the time. In our experience, most cougars cover a large territory and we generally only see evidence of them in the spring (perhaps when they drop cubs and need extra food?). They seem to move on to other climates (further up the mountain as weather warms up?) or hunting grounds by summer. We recently found a big deer killed by a cougar already this spring, so I will need to take precautions if I wander far from our homestead, esp. in case I might stumble on cubs. I am even more concerned when a cougar takes down a big deer (vs. fawn) that should have some instincts. When does act “spooky”, I suspect big bucks in rut or predators nearby.