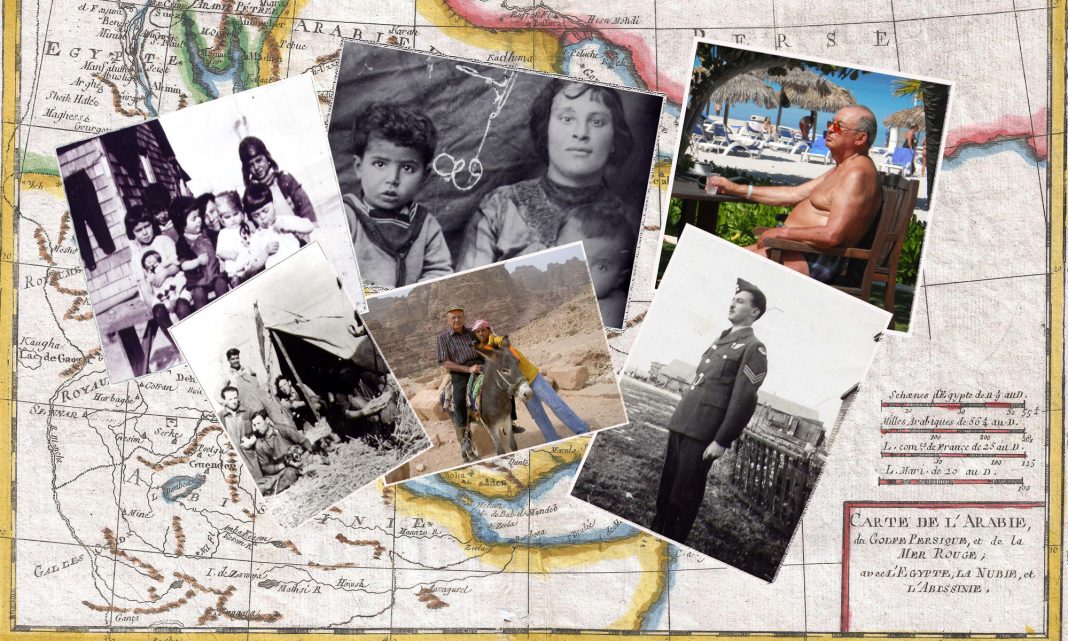

Habeeb Salloum, 95, a poet, world traveler, linguist, and author of recipe books on Middle Eastern cuisine, has written recipe articles for Backwoods Home Magazine for 19 years. The son of Syrian immigrant farmers, he lives in a small town near Toronto, Canada.

By Habeeb Salloum

Website Exclusive • August, 2019

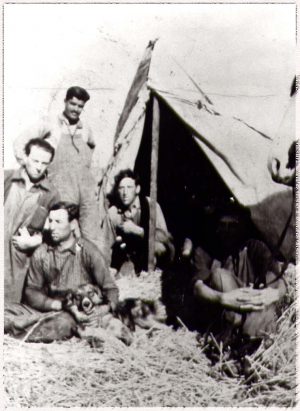

In the fall of the year 1923, my father Jiryas Yacqūb Sallūm (George Jacob Salloum) hurried back and forth in his town, the Qaraoun (Qarcawn), putting his affairs in order preparing to immigrate to Canada. The town, located in the Biqac Valley, was at that time under the French Mandate of Syria and Lebanon. Although excited about the prospect of starting a new life in a new land, he was nervous about leaving his young wife Shams, my older brother Adib (Eddie), and myself, not yet born. The world he was leaving was not a tranquil one. The French occupation of Syria and the unsettled conditions this brought in its wake had prompted many of the townspeople to leave for the Americas. My father, even though having made a good living as a merchant and farmer, wanted to enhance his status and decided that he, too, would join the exodus and try his luck in the beckoning world of the Americas.

A relative of his, Dāwūd Sallūm (David Salloum), a farmer in Hazenmore, a town in southern Saskatchewan, had written and asked if anyone from the village wanted to come and work for him as a farmhand. My father quickly wrote back and accepted the offer.

He arrived in Canada after travelling for two months, first crossing the Mediterranean and then France, sailed the Atlantic, landed in Quebec City, then took a train to Hazenmore, all this with only speaking colloquial Arabic. I remember as a child listening to amusing tales of his adventures in France, when, for instance, each time he asked for a drink of water in a restaurant or hotel he was served wine, never being able to make the waiters understand that he simply wanted water. He left the country believing that everyone in France drank nothing but wine. Tales such as this were often told, enthralling me in the same way that a child sits and listens captivated to the stories in Alice in Wonderland.

All That Glitters

My father’s work as a farm laborer lasted only a few months. The dream of America’s glittering gold, the dream of almost all immigrants in that era, was not to be found working sixteen hours a day on a farm for a few dollars a month. Moreover, having been an independent peasant farmer, he was not accustomed to being ordered around by another person, let alone a relative.

He left with no regrets and moved to the town of Gouvernor to live near Musa Salloum, another relative. Musa owned a general store, a mark of prosperity in that era, and agreed to outfit my father with a horse and buggy. He became a peddler selling clothing and trinkets to the farmers in the surrounding countryside. Many Syrian immigrants before him had worked and prospered in this profession, and he hoped to follow in their footsteps.

About one year later my mother, my brother (not yet three years old), and myself (less than a year old) followed in our father’s footsteps across the Mediterranean to France and then crossed the Atlantic. After two months, we arrived in Quebec City, then took the train to Gouvernor. The tales of how my mother traveled halfway around the world with no knowledge of French or English and the tribulations she encountered were, like my father’s stories, to hold us spellbound during many cold Saskatchewan winter nights.

By this time my father decided that he had had enough of peddling and its servile ways. Even though he was making a fair income, he hated the trade. He could not become accustomed to begging people to buy his few pieces of clothing and household trinkets.

Our family was growing. The one-room shack was becoming overcrowded. This gave my father the incentive to start searching for a farm. He wanted to own his own land. My parents knew that homesteading on the unbroken prairie was no easy task. Yet, they were young and ambitious and believed hard work was a fulfilling way of life, not a bogey to be feared.

Horses, Wagon, Plough

My father’s wish to be a farmer was soon fulfilled. He was granted by the federal government a quarter section of land as a homestead, eighteen miles north of the town of Val Marie. In the meantime, he had not been idle. Having saved a few hundred dollars from peddling, he bought another quarter section of land, a team of horses, a wagon, and a plough.

But we needed a home. The unfinished shell of a small structure left on the quarter section served as shelter from the heat and sun for our family during our first summer there. But my father knew he had to do something before the icy cold winter blasts compelled both man and animal to seek warm refuge.

Without money, Dad could not buy the materials he needed. This is when old world tradition kicked in. In Syria, people had built their homes from the soil and rock of the countryside. My father had helped many of his relatives and friends erect their homes, and he put this know-how to work.

Near the frail structure where we lived, a part of the land was pure clay. With my mother’s help, my father mixed clay with straw and water, creating a building mixture known as adobe. They filled it into the inner walls and ceiling of the frame structure, and when the adobe hardened, the building became home, comfortable in the extremes of both summer and winter. In later years, the adobe was painted and proved highly durable. I remember returning to visit the abandoned homestead 15 years after the home was built to find the walls were still like new.

That was our first summer, the summer we began with nothing to begin our life as farmers. It must have been an unnerving experience for my parents, but there was no turning back. Accustomed to a close-knit village life and when once they had been used to seeing relatives and friends daily now they were alone with not even a neighbor’s house in sight. On this empty stretch of near barren expanse, they were pioneers in a land they had chosen and were determined to settle, ready to conquer whatever came their way. And it was this homestead that became the basis of my life and when and where I begin to remember my early years.

My first memories are when I was but a young boy, about five or six years old. I remember looking across the empty spaces on our farmland, the same farmland that my father thought would set us on the road to prosperity. This God-forsaken land that had been taken from the indigenous people and given to settlers from around the world was to be the base of my life and evolvement thereafter. In the years to come on this land the whole structure of my future was laid.

Piles of Rocks

If asked today about my first childhood memories, a pile of rocks would be my answer. This is because of the thousands of rocks on our fields that had to be removed, by hand, in order to cultivate the land. A seemingly never-ending task, my brother and I were awakened in the early hours of the morning to go out and pick out the small stones, leaving the large boulders for my Dad to remove. It is little wonder then that I came to loathe the sight of piled rocks.

The weather and the land did not cooperate with our plans. Year after year, we sowed the land but with very little yield. We were able to grow a minimal amount of wheat in the sloughs (depressions in the land that collect moisture) which we made into burghul, an ingredient we used almost daily in our dishes. The best was when, on special occasions, Mother roasted a chicken and used burghul for the stuffing, a favorite of mine then and now. It was only in 1935 that I remember a successful crop of wheat and that was when we had moved from our homestead to another farm near Neville. Despite the heat, sun and parched land, my parents who had lived in the Middle East, were familiar with such climatic conditions and thus dug and planted a huge garden that we watered by hand from the well water. It served its purpose in providing food for our family. When our neighbors moved away due to the harsh conditions, we were able to thrive on our chickpeas, lentils, other garden vegetables, burghul, and yogurt.

Mother was a great cook. She could produce sumptuous meals and feasts using almost everything that grew in our garden. Lentils were used in several soups and stews, and at least once a week we enjoyed our mujaddara. Chores were only filled with joy knowing that upon completing them, mother would have a delicious meal waiting for us the moment we opened the door. I suppose our daily tasks were made easier with every aroma emanating from Mother’s cooking, each one more enticing than the other.

Picking stones is not my only childhood memory. Milking a cow, when we had one, cleaning the barn, feeding the chickens, and bringing water from the well were some of the chores that I was responsible for at this early age, chores I loathed. My parents knew how much I hated these tasks, but the unwritten code was that all of the children had work to do on the farm. I did try to escape from these responsibilities many a time. In fact, when I took my late wife, Fareeda, for the first time to Saskatchewan, many a story she learned about my early life on the farm from my parents. My father made it clear to my wife that Habeeb preferred reading rather than working and told her that he once caught me on top of the roof of our barn reading a book rather than milking the cow.

Inspiration

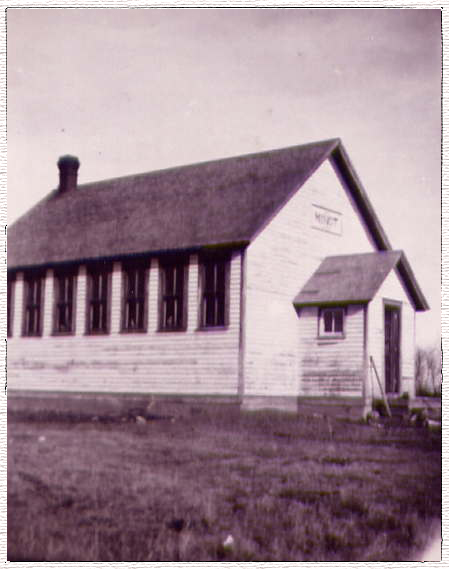

I was almost 8 years old when the first school opened up in our area but a year later it closed. By that time, we had moved to the new rented farm and there was a new school to attend. For me, Minot School was heaven-sent. The school which taught from grades 1 to 10 had a small library of a few hundred books. In the few years I attended I found the library to be my haven of knowledge and a friendly corner of life. I read and re-read all of the books, covering almost all subjects in the humanities, from history to geography and literary works. I even read the Bible three times! From all these books I learned about the outside world, not the isolated one in which I lived. My mind opened to other nations, peoples and cultures and I dreamed while asleep and during the grueling work in the fields, of the world I wanted to explore.

There was one drawback. I was bullied at school. “Out of my way Black Syrian,” were the words with which my peers welcomed me daily. The words were harsh forcing me to draw myself into a corner, and, as a result, made me put my focus on studying, reading, and writing. My older brother on the other hand responded by fighting back. His brawls to protect me and my other siblings at school almost became legendary. I could not comprehend why they hated Syrians and why they wanted to make us feel that we were different. We were ‘Black Syrians’ they kept reminding us. Those words continued to haunt me and had a great effect on my life.

The taunting at school forced me to seek my heritage. In the ensuing years I learned more and more about the Syrians and the contributions that they made to civilization. As I learned more, I came to understand that Syrians were part of the Arab world. And as the years went by, I studied Arabic and became proficient in the language. With the language, I studied the history and the great contributions that the Arabs made to world civilization in almost every aspect of life. I realized that being ‘Black Syrian’ was a positive.

Education had one of the greatest influences on my life but other incidents had their effects. I remember well as a young boy sitting at my father’s feet as he read aloud from Arabic newspapers about world events and news from Syria. I sat mesmerized because my father was reading classical Arabic that seemed to flow like poetry, different from our home spoken colloquial dialect. Watching me listen to my father, our family friend, Albert Hattum, remarked, “That son of yours is going to make something of himself in this world. Look at how he listens while other kids are playing!”

On another occasion, we were moving our belongings to the second farm. On that cold March day, as a lad of nine years, I was given sole charge of one of the four wagons that contained our worldly possessions. An impressed Albert Hattum said to my father, “You have a great boy. He will have a great future.” These two incidents may well have been the much-needed confidence and the self-assurance I needed that was lacking from my own schoolmates.

Also, ingrained in my memory, is the day my grade 10 teacher, Mrs. Castor, came by my family’s farm after learning that my dad could not afford to pay for my schoolbooks for the year. She met with my parents and stressed that I was an excellent student and recognized something different in me from that of my peers. Consequently, she emphasized that it was necessary for me to stay in school because she felt that I would have a great future. Her solution was that she would pay for my books herself.

These were words of inspiration from people that I will always remember.

The War

In 1939 at the age of almost 16, WWII began, and the world opened up before me. I left home to work in the war industry where I found a job in the city of Regina, Saskatchewan. On my own, and on weekends, I spent time in the city’s libraries, reading history and travel. I became obsessed with the art of writing, and the talent of being able to inscribe thoughts and ideas on paper. I felt that I too had a message for others to read. I therefore sat down and wrote a short novel about a Syrian immigrant to Canada using my family’s life as the example. When I went to visit my parents before leaving for Great Britain, I took the manuscript with me and left it in my old room at home. But alas, while I was overseas in the Air Force, my parents’ home burned down and with it went my novel.

In 1943 I joined the RCAF figuring that I would be able to see the world. At the same time, my older brother joined the Canadian navy.

Conscription into the Canadian army was the alternative, but I decided that I would be one step ahead by enlisting in the Air Force. I did my basic training in Mont Joli, Quebec then was sent overseas to Great Britain. Here I trained with the RAF and enjoyed life in the English pubs, searched for love, and learned the ropes of life. It was the first time I could make my own decisions, create my own schedules, and have the means to travel around England. This was also the first time I indulged in the flavors of Great Britain. Haggis, bangers and mash, mutton soup and bread pudding did not leave with me a great impression. After my first taste of sausage, I never ate English sausage again believing that they were made of sawdust. However, English fish and chips were not a disappointment, although all I could think about was Mom’s taratour that good old Syrian dipping sauce used for fish. This was my initiation to the sights and tastes outside of our Saskatchewan kitchen and I realized then that I missed my mother’s cooking.

Throughout these teen years, working in the war factories and travelling while in the RCAF, and then later in life when I married, had a family, then traveled the world, it was poetry that kept me company.

The greatest poet who first influenced me was the Canadian Robert Service. His words moved something inside me the first time I read them as a teenager. They seemed to be an omen for my future.

Restless

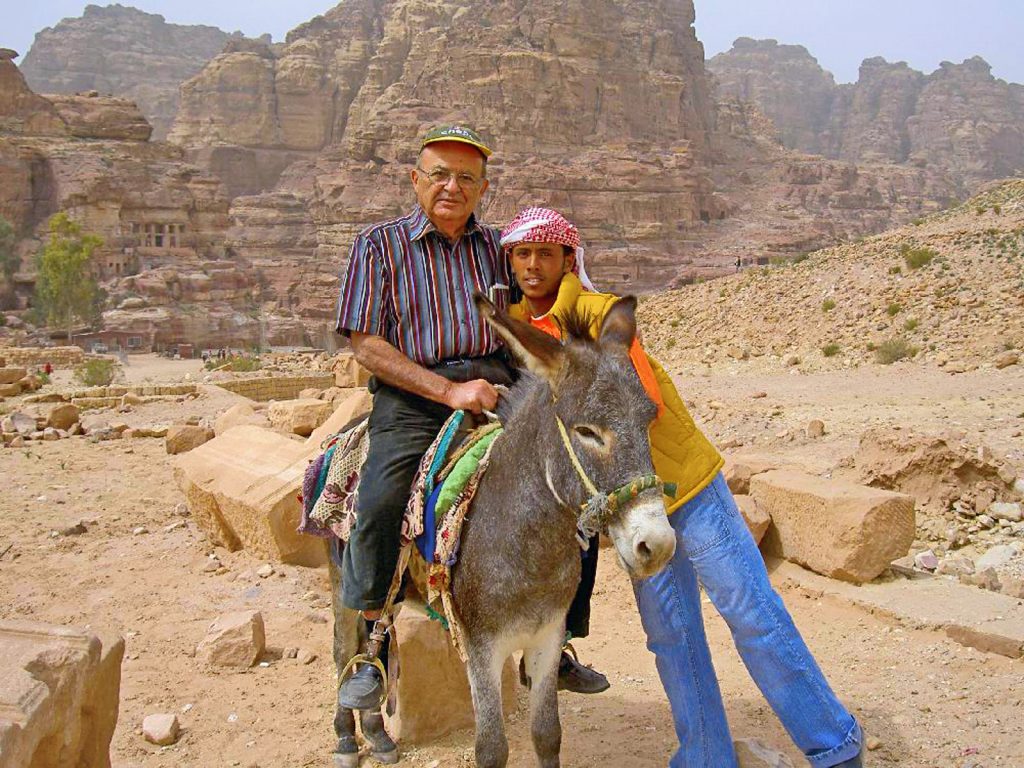

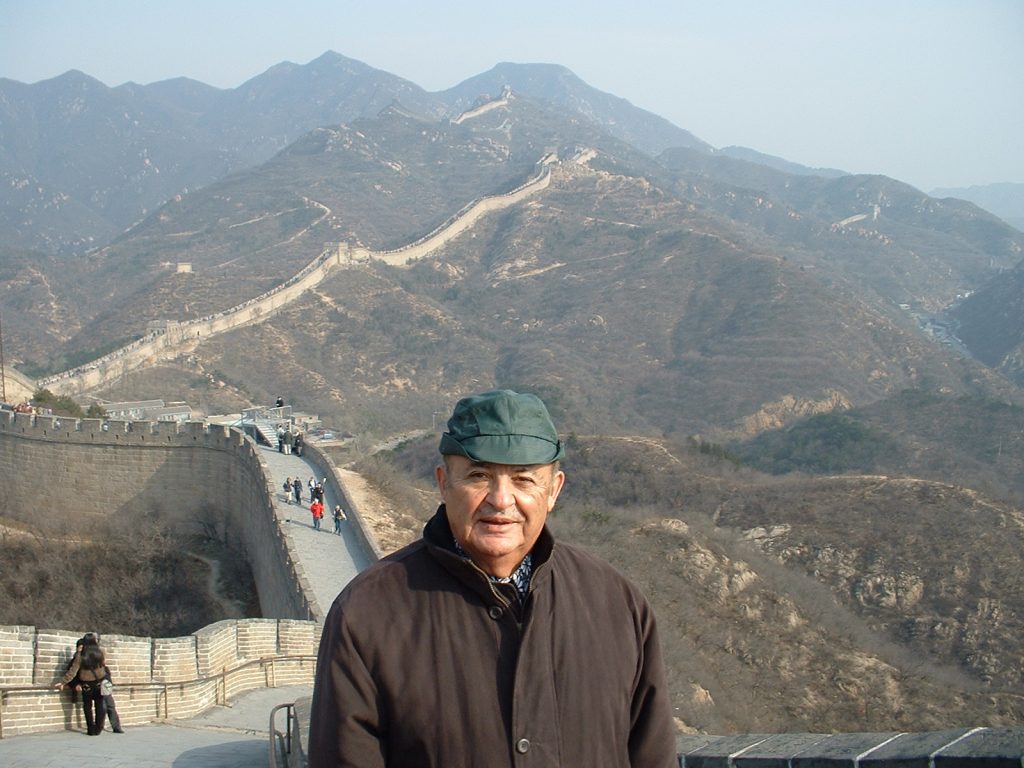

In those earlier years, I was restless, always seeking something beyond where I was and knowing that there was another world beyond the horizon. While others were content with what they had and how they lived, I felt that I did not fit into that mold. This is why I took it upon myself in the years that followed to go beyond that horizon, be it the Cameron Highlands in Malaysia or climbing the Great Wall of China and the Mayan pyramids in Mexico, sailing on a dhow in the Persian/Arabian Gulf or riding horseback across the Andes Mountains, and even reaching the peak of a frozen waterfall in Ontario in my 70s. Service’s words became my mantra:

…There’s a race of men that don’t fit in,

A race that can’t stay still;

So, they break the hearts of kith and kin,

And they roam the world at will.

They range the field and they rove the flood,

And they climb the mountain’s crest;

Theirs is the curse of the gypsy blood,

Even though the few snippets of Arabic poetry mom and dad would recite sounded great I did not clearly understand the essence of its meaning. Instead, I identified more with Robert Service and his verses of Canada’s cold north, for me, at least, indicatively similar to my Saskatchewan winter weather. Shakespeare also fascinated me, with the soliloquies of Marc Antony, Romeo and Hamlet. At school, when my classmates would complain endlessly about having to study Shakespeare, I, on the other hand, enjoyed his writings and could recite parts of his plays, which I often did, to myself.

And then my discovery of the great Persian poet Omar Khayyam whose works I read in English, translated by Edward Fitzgerald. In Khayyam’s words, man is but a pawn in the hands of destiny and the future beyond the control of man, and therefore one should live for the moment enjoying the pleasures of today.

Ah, fill the cup: – what boots it to repeat

How Time is slipping underneath our feet:

Unborn tomorrow, and dead yesterday,

Why fret about them if today be sweet!

How Khayyam, a mathematician and astronomer, wrote his quatrains (Rubaiyat) on his view of the world and man, and how each day should be lived like there is no tomorrow, inspired me to write my own, as yet unpublished, Prairie Rubaiyat. I wrote mine basing my verses on my life in southern Saskatchewan.

The wind blowing across Saskatchewan’s desert waste

Blew me misery and hardship and a bitter taste,

Made me forget my youthful thrills and joys

After I grew in years and worldly ways embraced.

Cruel were my schoolmates, taunting me ‘infidel’,

And ‘foreigner’ who came, in their land to dwell.

They must’ve all feared the strange and unknown,

The bully and even the beautiful mademoiselle.

Some say give us back our past yesteryears,

Others wait for the future with its joys and tears.

Man’s life is strewn with indecisions and sorrows,

But he must live it, before he disappears.

Settled

I returned to Canada in 1945 after my military service in Great Britain and headed straight to Vancouver to seek my fortune. I had no intention of returning to farm life after having tasted the joys of the outside world. Farm life had been a tedious one, with memories of drought, Russian thistles and dust storms. However, the pleasant memories were those of the great meals that my mother made, dishes that would eventually lead me, later on, to write a series of cookbooks. My Arab Cooking on a Saskatchewan Homestead (CPRC Press 2005) and later the revised edition Arab Cooking on a Prairie Homestead (University of Regina Press 2017) reflect my mother’s kitchen throughout the years we farmed and snippets of our life there. Also related to my early homesteading years was my cookbook Bison Delights: Middle Eastern Cuisine, Western Style (CPRC Press 2010) remembering the bison who once roamed the land on which we settled.

While I worked at various labor jobs in Vancouver, at the same time, I felt it was time to settle down. With my plans set for marriage, I knew that I needed to find a good stable job. Toronto beckoned and in 1948 I arrived in Ontario’s largest city where I began my long employment career with the Department of National Revenue.

It was also here in Toronto where I met my future wife, Fareeda, to whom I was first introduced at a bowling tournament where the Toronto Syrian Bowling League met weekly. We courted then married in 1950. My wife brought with her mother’s Damascene dishes, one of which remains my favorite, safsouf salad. Even more exciting in this large urban center was the social interaction with the new immigrants from various Arab countries. With this interaction I was introduced to many new dishes from the Arab world. For instance, I enjoyed Moroccan food for the first time when a friend of mine, Idris al-Kittani and his wife, Amina, stayed with us for a month. The Moroccan food Amina prepared was my first introduction to North African cuisine and I loved it. The tajins and couscous were a world apart from our Syrian burghul, chickpea and lentil dishes. Palestinian musakhkhan with its onions and sumac was a unique way to prepare chicken, and Tunisian breeks were the epitome of fast food. Abbas and Lutfiya, Egyptian friends, introduced us to fteer, a flaky pastry drenched in honey that was almost as sweet and tasty as my Mother’s baklawa.

Flavors, aromas and taste knew no boundaries and I was intent on imparting these to the rest of the world. This culminated in the publication of my first cookbook, From the Land of Figs and Olives (Interlink 1997). And then with the new wave of vegetarian cooking on the rise, my second cookbook, Classic Vegetarian Cooking from the Middle East and North Africa (Interlink) made its debut in 1999.

Arabia

I worked hard to improve my position in the Department of National Revenue and ended up in the top ranks of Customs and Excise. While working, I decided to upgrade my education and completed a bachelor’s degree taking courses at night-school. In fact, over many years, I continued to take courses of interest during the evenings such as Spanish and French, knowing well enough that I would need these languages for my future research and travels overseas, this while continuing to increase my knowledge of the Arabic language.

And it was during these years of work and study that I began to write more poetry and articles for my own pleasure. They would be the basis for future articles and any books that I would write for I had planned to see the rest of Canada and to travel the world and write about my experiences, especially the Arab countries.

My love of history and my fascination with the Arabic language led me and my colleague, the late James Peters, to compile a study of English words of Arabic origin, Arabic Contributions to the English Vocabulary (Librairie du Liban 1996). A new revised edition is in the works with my daughter Leila. In the same vein, studying the Spanish language opened my world to a new history of how languages are influenced by others. Case in point, the impact of the Arabic language on Spanish became my obsession. For the past 20 years, I have collected, along with my daughter Muna, Spanish words of Arabic origin, compiled as a lexicon and near ready for publication.

Cuisine Influence

When my daughters graduated from university, I planned a trip to Spain with my family. I rented a car and toured the country for one month visiting sites of Moorish origin. As a result, upon my return home, I wrote my first published book Journeys Back to Arab Spain (Middle East Studies Centre 1994) in which I describe our journey of adventure seeking out the remnants of the Arabs in Spain. The trip not only included history but also the food of the country. I became obsessed with the flavors of Andalucía especially their tapas. Back in Toronto, immediately following the trip, I announced to my family that I had found my new niche in life. Cooking.

In addition to creating my own versions of these tapas, such as Spain’s tender fried liver, I also began my venture into creating new dishes and re-creating traditional dishes especially from the Arab world. Some of these traditional dishes dated back to the medieval period and when my daughter, Muna, began her research on the foods of the medieval Arab world, I, and my other daughter, jumped on the bandwagon. We discovered a world of luxury and nutrition based on 10th to 13th century Arabic cooking manuals. Our goal was to translate, at least a few hundred recipes, redact them and make them in our kitchen. This resulted in two unique books, Scheherazade’s Feasts: Foods of the Medieval Arab World (University of Pennsylvania Press 2013) and Sweet Delights from a Thousand and One Nights: The Story of Traditional Arab Sweets (I.B. Tauris 2013).

My trip to Spain was my pathfinder to my future explorations of the world. Over the past 50 years, I have traveled to over 100 countries, touring modern and historical sites and experiencing cultures and traditions, part of which is cuisine. And I have my favorites.

From among these is that of the Moroccan. During those memorable numerous trips that I made to the country, I dined on fabulous dishes with a long history, such as hareera, a one-dish meal hearty soup.

Of course, home is where the heart is and it was in Syria, the heart of the Middle East, that, still held the memories of home and my mother’s cooking. With every bite of almost every dish, I had on my numerous trips there, memories of family and comfort were re-lived. From among these is kubba, Syria’s national dish. Cooked in various ways, one of my favorites is the deep-fried, kubba qaraas.

The Scent of Pomegranates

To round off my trips to the Arab World, I made a series of journeys to the Arab Gulf countries, a seemingly futuristic world I envisioned as being 25th century. There I found an intriguing fusion of Arab, western and other cuisines, thus prompting me to write a cookbook called The Arabian Nights Cookbook: From Lamb Kebabs to Baba Ghanouj, Delicious Homestyle Arabian Cooking (Tuttle 2010) which features both the traditional and the contemporary cuisine of the region. Above all, I remember feasting on stuffed lamb (kharouf mahshee), considered the regal dish of the area. The book was so successful that a new edition was published.

In between my trips to the Arab World, I visited numerous Asian countries such as Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia and China where I relished the top foods of Asia. On my return home, I had my book published Asian Cooking Made Simple: a Culinary Journey along the Silk Road and Beyond (Sweet Grass Books/Farcountry Press 2014), so that others could enjoy the dishes that I had tasted. Of course, there were other countries that I visited. These include Yemen, countries of South and Central America, countries in Europe and the Caribbean. From these visits I wrote about their foods and the impact the Arabs had on these kitchens.

Although my travelling has lessened, somewhat, I continue to write. It seems my mind never stops. There have been many instances when I wake at night with an idea for a new article or book. One of the most recent is the exciting new project that I have co-authored with my daughters on 18th and 19th century dishes of Greater Syria. The Scent of Pomegranates and Rosewater: Reviving the Beautiful Food Traditions of Syria (Arsenal Pulp Press) was published in October 2018. These are the dishes of my grandparents and great-grandparents’ generations.

I am the son of Syrian immigrants, pioneers in western Canada who formed, at that time, part of the mosaic of the growing Canadian nation. Their determination and struggles to overcome whatever faced them and do so successfully instilled in me the same qualities – to grab the bull by the horns and venture forward, knowing dreams can be realized and barriers crossed.

A few of Habeeb’s favorite recipes appear below.

Safsouf – Burghul, Parsley and Chickpea Salad

Serves 8

This salad is a unique type of crunchy tabbouleh. To make the crunchiest safsouf, it is best to soak 1/2 cup dried chickpeas overnight then drain. A handful at a time, wrap in a clean towel and break them up with a rolling pin then remove the loose skins before using.

1/2 cup fine (#1) burghul

3 medium tomatoes, finely chopped

4 tbsp. olive oil

4 tbsp. lemon juice

1 tsp. salt

1/2 teaspoon black pepper

1 large bunch parsley, stemmed and finely chopped

1 cup cooked chickpeas

1 small bunch green onions, finely chopped

1 medium cucumber, about 6-in long, finely chopped

1 1/2 cups finely chopped mint

Rinse burghul and let sit in a fine mesh strainer to drain any excess water. Transfer to a salad bowl and stir in the tomatoes. Cover and refrigerate for one half hour.

In a small bowl, mix oil, lemon juice, salt and pepper, then set aside.

Add remaining ingredients to the burghul and tomatoes, then stir in the dressing. Chill for 1 hour, then serve.

Liver Tapas

Serves 4

This is my version of the liver tapas I enjoyed in Spain.

4 cloves garlic, crushed

1 small hot pepper, seeded and very finely chopped

1/4 cup chopped parsley

1/4 cup olive oil

1 pound calf liver, cut into 1/2-in cubes

3/4 teaspoon salt

1/2 teaspoon black pepper

1/2 teaspoon allspice

In a bowl, combine the garlic, hot pepper and parsley and set aside.

In a frying pan, heat oil on medium, add the liver, and stir-fry until it begins to brown. Add the garlic mixture, salt, black pepper, and allspice. Stir-fry for a few more minutes until done to taste.

Hareera – Hearty Chickpea and Meat Soup

Serves 10 to 12

Hareera is one of Morocco’s oldest and most popular soups. The first taste I had of it was when the wife of my Moroccan friend prepared it for us.

4 tablespoons butter

1/2-pound lamb or beef, cut into small pieces

2 medium onions, finely chopped

4 cloves garlic, crushed

1/2 cup finely chopped cilantro

1 can chickpeas (19 oz), drained and rinsed

2 cups stewed tomatoes

1/2 cup brown lentils, rinsed

9 cups water

2 teaspoons salt

1 ½ teaspoons ground ginger

1 teaspoon paprika

1 teaspoon black pepper

1 teaspoon cumin

1/4 teaspoon cayenne

1/4 cup long grain white rice

4 tablespoons lemon juice

In a large saucepan, melt the butter; then sauté the meat over medium heat for 10 minutes.

Add the onion, garlic, and cilantro, then stir-fry for a further 10 minutes. Stir in the remaining ingredients except the rice and lemon juice; then bring to a boil. Cover and cook over medium heat for 40 minutes, stirring occasionally. Stir in the rice and cook for a further 20 minutes, then stir in the lemon juice and serve immediately.

Mujuddara – Lentil Potage

Serves 4 to 6

Out of the hundreds of vegetarian dishes I’ve tasted, mujaddara remains my favorite, from the time of the homesteading years until today.

1 cup brown or green lentils, rinsed

6 cups water

6 tablespoons olive oil

2 large onions, finely chopped

1/4 cup rice or coarse burghul, rinsed

3/4 teaspoon salt

1/2 teaspoon black pepper

1/2 teaspoon cumin

1/2 teaspoon ground coriander seed

In a saucepan, bring the lentils and water to a boil, then cover and cook over medium heat for 30 minutes.

While the lentils are cooking, in a frying pan, heat the oil on medium and sauté the onions until golden. Add the onions with their oil and the remaining ingredients to the lentils, then cover and cook for a further 20 minutes or until the lentils and rice or burghul are soft but not mushy, stirring occasionally. Remove from the heat then serve.

Meat and Egg Pie – Breek

Makes 12 pies

It was in Tunisia that I had my first experience eating breek. Sold all over the country in fast-food stalls, breeks are as popular as hamburgers are in North America.

1 large egg

4 tablespoons butter

1/2-pound lean ground beef or lamb

1 medium onion, finely chopped

2 cloves garlic, crushed

4 tablespoons finely chopped fresh coriander leaves (cilantro)

1 small hot pepper, seeded and finely chopped

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon cumin

1/2 teaspoon cinnamon

1/2 teaspoon allspice

1/2 teaspoon finely ground black pepper

1/2 cup crumbled feta cheese

24 sheets of filo dough

1/4 butter, melted

12 small eggs

Oil for frying

Beat the large egg in a small bowl then set aside.

Prepare filling by melting butter in a frying pan, then sauté meat over medium heat for 5 minutes. Stir in onion, garlic, coriander leaves, hot pepper, salt, cumin, cinnamon, allspice and pepper, then stir-fry for 10 minutes or until meat is cooked. Remove from heat, then stir in cheese and set aside to cool. Divide into 12 equal portions.

Place oil in frying pan to about 1/2-inch deep then heat over medium.

Take a sheet of filo dough, brush edges lightly with melted butter then place another sheet of filo dough on top. Fold twice then slightly fold the ends in on 2 sides to make a square. Place 1 portion of the filling in the center and make a well in the filling. Lightly brush edges of square with beaten egg then break one egg into the well. Fold 2 ends of the square to make a triangle then press the edges together to seal. Carefully slide breek into hot oil and fry for about 30 seconds or until golden on one side. Turn over gently using 2 spatulas and cook on other side until golden, about 30 seconds. Carefully lift breek from oil and place on paper towel to drain excess oil. Let rest for a minute then transfer to serving platter. Repeat the process until all the breeks are done. Serve immediately.

Kubba Qaraas – Deep-fried Kibbeh

Serves 6 to 8

To make the stuffing:

3 tablespoons butter

1/4 cup pine nuts or chopped walnuts

Pound ground lamb or beef

1 medium onion, finely chopped

1/4 teaspoon nutmeg

3/4 teaspoon allspice

1/4 teaspoon cinnamon

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/2 teaspoon black pepper

In a frying pan, melt the butter, then add the nuts and sauté over medium-low heat until golden. Stir in the meat and sauté for 10 minutes over medium heat. Add the remaining ingredients and sauté until the onion is limp. Set aside.

To make the kubba:

2 cups fine (#1) burghul

2 pounds lean lamb or beef

2 medium onions, finely chopped

1 1/2 teaspoons salt

1 teaspoon black pepper

1 teaspoon allspice

1 teaspoon cumin

1/2 teaspoon cinnamon

Pinch of cayenne

2 teaspoons dried mint, crushed

Soak the burghul in cold water for 10 minutes. Drain by squeezing out the water in a strainer and set aside.

In a food processor, process the meat until it is finely ground. Transfer to a mixing bowl and add the burhul and the remaining ingredients. Mix thoroughly then process a portion at a time until all is well ground and mixed.

Take a small handful of kubba the size of an egg. Holding the ball in one hand and using your forefinger on the other hand, make a hole in the middle. Shape by turning and pressing until you have an elongated, oval shell slightly less than 1/4 in thickness and about 3 in long.

Place 1 tablespoon of stuffing into the hollow shell, then pinch the opening making an egg-like shape. (Dip hands slightly in cold water to help shape and close the shells). Place on a tray until ready to fry.

To fry the kubba:

Use oil for deep-frying. In a saucepan, heat the oil over medium-high, then deep-fry the kubba until golden brown. Let sit on paper towels to absorb any excess oil, then serve.

Dajaaj Mihshee bi-Burghul – Chicken with Burghul Stuffing

Serves 6 to 8

My mother often prepared this dish on holidays on the homestead and it is still my favorite way to eat roast chicken.

1/2 cup pine nuts

1/2 cup butter

1/2 cup finely chopped onions

1 cup coarse (#3) burghul, soaked in water for 5 minutes and drained

1 cup chicken stock

1/4 cup finely chopped parsley

1/2 teaspoon allspice

1 teaspoon ground coriander seed

1 1/2 teaspoons salt

3/4 teaspoon black pepper

1 teaspoon cinnamon

1 roasting chicken (4-to 5-pounds), cleaned, washed and patted dry

To make the stuffing, in a frying pan, melt the butter, then sauté the pine nuts over low heat until golden. Remove with a slotted spoon and set aside.

Sauté the onions in the same butter over medium-low for 10 minutes, then add the burghul and stir-fry for a few minutes. Add the chicken stock, parsley, allspice, coriander, 1/2 teaspoon of the salt, and 1/4 teaspoon of the pepper. Stir over medium heat until the stock is absorbed. Leave to cool.

Add the pine nuts to the cooled stuffing and mix well. Stuff the cavity of the chicken, sew or skewer closed, and place the chicken in a roaster. Any leftover stuffing can be placed in the neck opening. Brush the chicken with additional melted butter and sprinkle all over with the remaining salt and pepper, and the cinnamon. Roast covered in a 350oF pre-heated oven for 2 hours. Remove the cover and allow to cook another 30 minutes or until browned. Serve hot.

Musakhkhan – Chicken with Sumac

Serves 4 to 6

Musakhkhan is the national dish of Palestine. On a visit to Qalqilya in the early 1960s, my wife and I were served this dish as a sign of honour and welcome.

3- to 4-pound chicken cut into serving pieces

6 cardamom seeds, crushed

3/4 cup olive oil

4 large onions, thinly sliced

1 teaspoon salt

1/2 teaspoon black pepper

1/2 teaspoon allspice

1/4 cup pine nuts

1/2 cup sumac

4 small loaves Arab bread

In a saucepan, place chicken pieces and 1/2 of the crushed cardamom seeds and cover with water. Cook over medium heat until the chicken is tender, then remove the chicken pieces and set aside.

In the meantime, in a saucepan, place 1/2 cup of the oil, onions, salt, pepper, allspice and the remaining cardamom, then simmer uncovered over low heat for about 30 minutes or until onions are translucent.

While the onions are simmering, sauté the pine nuts in remaining 1/4 cup of oil until golden then add the sumac to the cooked onions, stir and allow to cool.

Split open the bread loaves; then arrange them in a greased, round or oval deep casserole, spreading a portion of the onion-sumac mixture on each piece of bread, using about half of the mixture. Top evenly with the chicken pieces, then spread the remaining 1/2 of the onion-sumac mixture over the chicken. Cover with thick brown paper and bake in a 350° F pre-heated oven for 40 minutes.

Serve immediately while hot, serving a portion of the bread with each chicken piece. Or, even better, allow each person to take a piece of bread by hand and scoop up the chicken.

Steamed Cantonese-style Fish

Serves 4

Ironically, it was in a small Chinese restaurant in Regina, Saskatchewan that I first tasted this healthy Asian low-fat dish.

2- to 3- pounds salmon or similar fish steaks

1 1/2 teaspoons salt

2 tablespoons finely grated fresh ginger

4 tablespoons finely chopped green onion

1 small red bell pepper, seeded and cut into thin strips

4 tablespoons light soy sauce

2 teaspoons peanut oil

3 teaspoons light sesame oil

2 tablespoons finely chopped fresh cilantro

Rub fish with salt and place in the perforated upper pan of a double boiler, then set aside.

Fill the lower pan of the double boiler with water and bring to boil. Nestle the upper pan (with the fish) over the lower pan. Spread ginger over the fish.

Allow fish to steam over high heat for 10 to 15 minutes. It is cooked when the fish begins to flake slightly but remains moist.

Remove the steamed fish and place on a platter. Spread the green onion and red pepper strips over top, then drizzle with the soy sauce.

Heat the peanut and sesame oils in a small saucepan until they begin to smoke, then immediately pour them over the fish. Spread cilantro over top and immediately serve with cooked rice.

Kharoof Mihshee – Stuffed Whole Lamb

Serves 30

To be served this by an Arab host is the epitome of honor and hospitality.

6 tablespoons salt

A spring lamb weighting between 20 and 25 pounds

2 teaspoons black pepper

2 teaspoons allspice

Take 5 tablespoons of the salt and rub the lamb inside and out. Wash the lamb in cold water, then dry with paper towels. Mix the remaining salt, pepper, and allspice, then sprinkle the mixture inside and outside the lamb. Set the lamb aside and prepare the stuffing.

The stuffing:

3 pounds lamb, diced into very small pieces

1 cup butter

5 cups long grain white rice, rinsed

2 teaspoons salt

1/2 teaspoon nutmeg

1 teaspoon cinnamon

6 cardamom seeds, crushed

1 tablespoon black pepper

1 tablespoon allspice

8 cups water

1 cup pine nuts

1 cup blanched almonds

In a large saucepan, brown the meat lightly in 1/2 cup of the butter over medium heat. Add the rice and all the remaining ingredients except the water, pine nuts, and almonds. Stir until the spices are well mixed in, then add the water. Cover and simmer over low heat for 30 minutes.

While the rice is cooking, sauté over medium-low the pine nuts and almonds in the remaining butter until golden. Remove the saucepan form the heat and add the pine nuts and almonds, then mix well and set aside.

Stuffing and cooking the lamb:

Sew the cavity of the lamb closed with thick white linen thread, leaving an opening large enough for stuffing the animal. Stuff the lamb with the prepared stuffing, then sew up the opening, closing it completely. Place the lamb in a large deep pan and set aside.

Pre-heat the oven to 450oF, then place the lamb in the oven and cook for 15 minutes. Cover with aluminum foil, return to the oven, and reduce the oven temperature to 350oF. Cook until the lamb is tender; the cooking time is usually 30 minutes per pound, or 10 hours for a 20-pound lamb.

When ready to serve, place the lamb on a large platter and set the platter in the middle of the serving table. Carefully remove the linen thread to expose the stuffing. The lamb should be served piping hot.

Baqlawa – Baklawa

Makes about 30 pieces

Baklawa is truly the queen of Arab pastries.

Prepare the syrup:

2 cups sugar

1 cup water

2 tablespoons lemon juice

1 tablespoon orange blossom water (mazahar)

In a medium sized saucepan, stir together the sugar and the water then bring to a boil over medium heat. Continue simmering for 7 minutes then stir in the lemon juice and allow to simmer for 7 more minutes. Stir in the orange blossom water, reduce the heat and cook for a further 1 minute. Set aside and allow to cool before using

Preparing the baqlawa:

2 cups walnuts, chopped

1 cup sugar

2 cups melted unsalted butter

1 tablespoon orange blossom water

1-pound filo dough, thawed according to package instructions

To make the stuffing for the baklawa, in a mixing bowl, combine walnuts, sugar, 1/4 cup of the butter, and orange blossom water, then set aside.

Butter a 9- X 13-inch baking pan, then set aside.

Remove filo sheets from the package, unroll and spread out on a kitchen towel. Cover the unused sheets with another towel or cling-wrap to prevent it from drying out as you work. Take one sheet and place in the baking pan, folding back any overlap, then brush with butter. Keep repeating the procedure until one-half of package is used. Place walnut mixture over buttered layers then spread evenly.

Take one sheet of filo and spread over walnut mixture and gently brush with butter then continue this procedure until remainder of the dough is used. Pour remaining butter evenly over top.

Pre-heat oven to 400° F.

With a sharp knife, carefully cut into approximately 2-inch square or diamond shapes. Bake for 5 minutes, then lower the heat to 300° F and bake for 45 minutes or until the sides are golden. Immediately pour the basic syrup evenly over the top.

Allow to cool before serving.

Wow. Wonderful story of proud Arab in the end of the world from Arabia. How his Arabic roots persisted, and he strived to encyclopedia everything Arabic. I wish good life to his progeny and not to forget their roots. Like the phoenix phoenicia never does.

My, oh, my these recipes sound scrumptious! Interesting to see cumin and cinnamon in the same dish. In my house cumin is for chili, and cinnamon for toast or pies, but never the two spices together! I’ll have to try some of these recipes. I really enjoyed your condensed life story! God Bless, from far northern California!