By Wren Everett

The beans came to me as an accident.

In the early spring of 2023, I was scouring The Exchange (exchange.seedsavers.org/home) — an online seed-savers trading post of sorts — looking for squash seeds. My previous squash efforts had been perpetually foiled by drought and squash bug attacks, and so I had been looking for Ozark-based growers who had squash seeds that actually wanted to grow in this hot, rocky, bug-infested climate. How I ended up on a New York-based grower’s page is beyond my remembering now, but there I was, contacting a grower named Allison and asking if she would be willing to trade squash seeds for some of my medicinal perennial seeds.

Seed-savers tend to be a generous bunch, so when she learned that I was trying to breed my own landrace of squash, she offered to clear out some of her older seeds and send them my direction. Better me try to get them to grow than for them to slowly lose viability in a drawer. But then she offered one more thing — an heirloom pole bean that she said she’d throw in the envelope as a bonus, if I was interested.

Now, I have never met a seed I didn’t like, so of course I said I’d take them. I was especially interested when she detailed that the beans were an extremely rare Italian variety that she’d gotten from a now-closed seed shop. “They’re called ‘Grandma Gina’ beans,” she explained. “I got them in 2017 or 2018. It would be good to have others growing them — I’m not sure how long I can maintain so many things.”

Interest firmly piqued, I put Allison’s herb seeds in an envelope, sent them off to New York, and waited for my seeds to arrive in response. In the waiting meantime, I decided to try and research these apparently unusual beans to see if I could find more about them. All my internet searches revealed … nothing but Allison’s own seed listing on The Exchange. Apparently no one was selling these beans in 2023.

Rare heirlooms

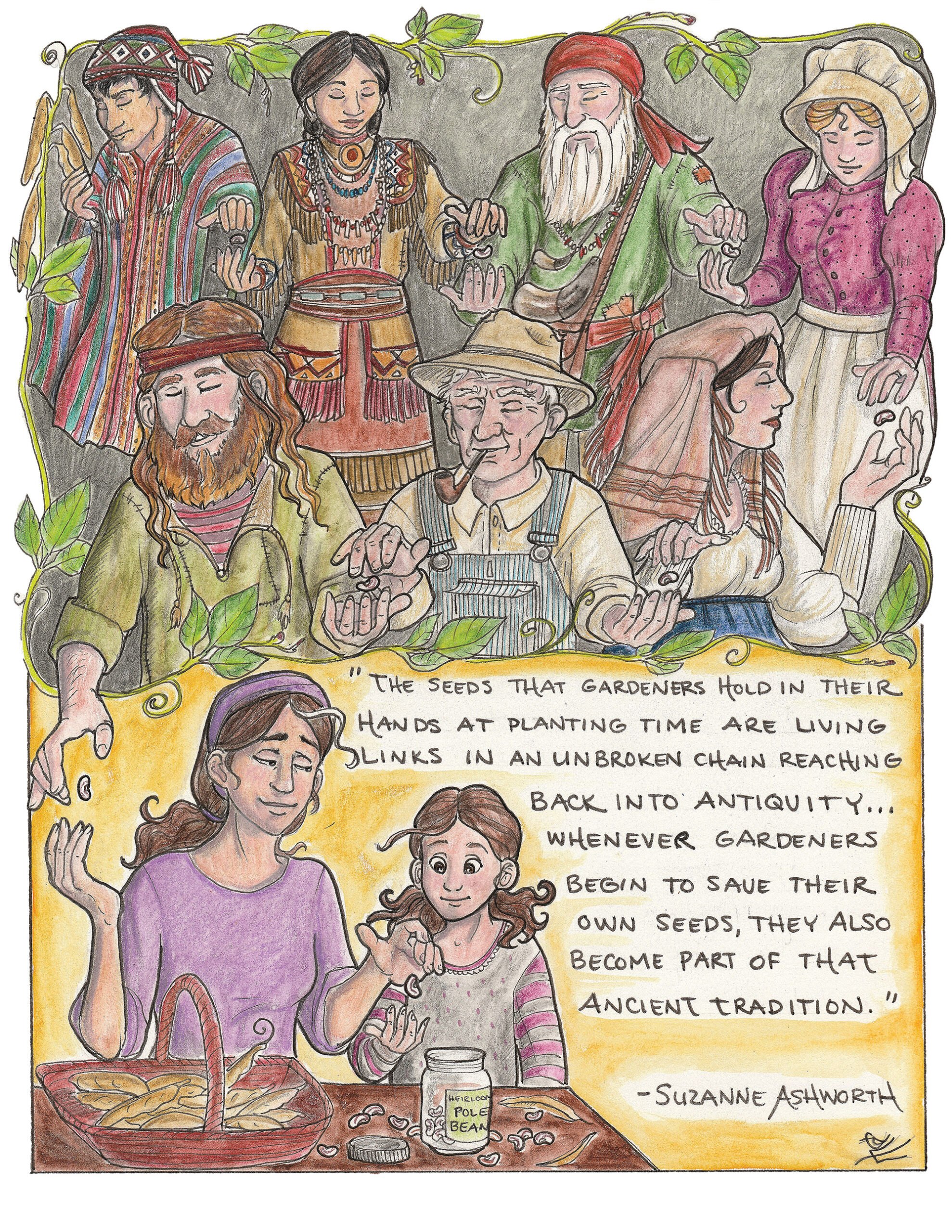

The scarcity of varieties like Allison’s mysterious “Grandma Gina” beans is nothing new. Many excellent varieties of seeds have begun disappearing because no one is saving them anymore. Granny may have grown a garden and saved all her own seeds, just like her granny did, but if the grandkids aren’t interested in gardening, the seed-line held together by generations comes to an abrupt, permanent stop. For many who even garden at all, it’s a lot easier to pick up a packet of whatever trademarked hybrid du jour seeds are being sold at the local Walmart. Those homogenized seed packets, however, don’t represent the huge spectrum of beautifully complex varieties that have been created over all of humanity’s agricultural past. Not by a long shot.

Huge bean seeds with their characteristic seed coat cracks

Some of them have entered the “mainstream” — you can identify them by the fact that most of them still bear a family name, like “Thelma Sanders’ Sweet Potato Squash” or “Jimmy Nardello Pepper.” But there’s a whole world of diverse, relatively unknown, excellent seeds out there, existing well beyond the scope of any seed catalog or garden store display rack. Rather than being cultivated by a company, they are stewarded by a family that has grown and enjoyed them for generations. In some instances, they were among some of the few, precious items brought across the Atlantic — a little bit of home brought to an unfamiliar new continent, a connection to an identity that could be given to the next generation. Rather than being selected for commercial viability, these seeds were selected directly by their own growers and eaters for unparalleled flavor or texture or hardiness or long storage. Rather than being hybridized or genetically modified, they are propagated the way they were designed — from seed to seed, from garden to jar to garden again. And rather than being someone’s protected trademark, they are only extant as long as someone remembers to plant them before they lose viability.

In short, they’re special, and they’re rare, and many of them are on the cusp of being forgotten and lost.

So it was with these “Grandma Gina” beans.

Growing the beans

The envelope arrived in my PO box a few weeks later. I tore it open, pulled out the squash seeds that had been the impetus for the trade in the first place, and the packet of beans dropped into my lap. Opening it revealed the absolute biggest pole bean seeds I’d ever seen in my life. Glossy, black things, gleaming like polished onyx, with small cracks in their seed coats that revealed a starkly white interior. Allison had assured me that the seeds were still viable despite the coat cracks — that they might even aid in germination. I rolled a few around my palm.

I had already planted “Turkey Craw” pole beans that year, but I couldn’t resist secreting a few “Ginas” in a separate bed. Bean varieties only need to be separated by a few dozen feet to produce pure seed, so a garden on the northern side of my property, hundreds of feet away from my Turkey Craw, would be a perfect place to give them a chance to grow. I planted half the packet — a nice test plot of 12 plants, if they sprouted.

To say these things grew fast was an understatement. I’ve always been impressed by the vigor with which beans emerge from the soil, suddenly erupting with their swollen seed leaves spreading wide and releasing their first true leaves. But these beans — they fairly leapt from the soil, sometimes wearing a retained clump of soil atop their sprouts like a hat. The sprouts were not what I was used to — they were great, purple-streaked things, twice the size of the Turkey Craw sprouts.

The sprouting seeds are a beautiful sight in spring.

True to Allison’s word, every one of the 12 cracked-coat seeds grew. As they twined around their cattle-panel trellis, unexpectedly magenta-purple flowers emerged, peeking out from under the leaves like bashful eyes. When they grew their seed pods, they emerged as flat, Roma-style things. I picked the first few pods at the size I thought was right for “normal” beans, but, as I soon found out, these were not normal beans. They were enormous. The beefy pods were well past seven inches long before they began to fill with seeds, making filling my harvest basket a brief procedure.

In the kitchen, I sliced them on a bias and sautéed them in olive oil with minced garlic that had just been harvested two beds down. A sprinkle of salt, cayenne, and fresh-cracked pepper was all they needed to be served — the meaty texture and rich flavor certainly carried its own weight. The beans were tender, stringless, delicious, and never, ever made it to the refrigerator.

After that first meal, I stared at my experimental planting, wishing I had planted the entire envelope of seeds. Instead of harvesting all of the pods for lunch, however, I began letting them mature. I wanted more seeds. And the only way I was going to get them for next year’s planting was to make them on my own. Unlike most other seeds I’d dealt with, there was no “backup,” no store to revisit, no company reserve of replacement seeds.

Seed saving

Seed saving seems to be one of those activities somewhat relegated to “special interest” in the gardening world. Sure you can save seeds if you really want to, but it’s not like you have to do it. When glossy, gorgeously-photographed seed catalogs are available in your mailbox at a click, or when professionally-pixellated websites fill the internet, saving seeds must seem a little backward, a little anachronistic.

… At least, that’s how it seems.

I’m convinced, however, that the two most important skills a gardener can gain are the ability to both grow plants from seeds and save seeds from those plants. Without that knowledge, a garden lasts only as long as the growing season is long, and though it has the trappings of self-sufficiency, is just as dependent on purchased products as packaged bread and air conditioning repairs.

When it comes to beans, thankfully, growing them is a very easy procedure. Protect their young sprouts from rabbits and their leaves from browsing deer — sometimes far easier said than done! — and you’ve done the bulk of the work. Pole beans like Turkey Craw and Grandma Gina beans will require some sort of trellis. I’ve had good results with using cattle panels as an easy-to-erect, nearly-instant trellis.

Saving bean seeds is about as easy as growing them. First off, if you want to save pure seeds, separate different bean cultivars by at least 30 feet. Then, allow the seeds to grow to maturity until their pods have dried to a papery straw-yellow color on the plant. This can sometimes take longer than you expect, but it’s not a process that can be rushed. Then, harvest the pods on a dry day, and separate the beans from the pods — a task easily done by loading your harvest of seed beans into a cloth bag and stomping the daylights out of it. Inevitably, there will be a discolored, insect-bitten, or sprouted bean in the mix. Separate those out, then allow the seeds to dry for at least two more weeks. Label and put in dry storage for next year, and just like that, you have achieved bean self-sufficiency.

Seeds becoming seeds

Saving the Gina bean was more challenging than I expected. You see, these beans had been shared by someone in the New York area, who had gotten them from someone also in the New York area (according to Allison’s brief description). The past few generations of these beans had been grown and saved in a place that was several growing zones cooler than my hot, dry Ozark hill. The beans seemed to know it, too. I had a lot of trouble with pollination — we had historic heat waves that summer, with temperatures occasionally hitting 103 and even 107 degrees Fahrenheit. Many of the pods I allowed to reach maturity were full of underdeveloped seeds … or empty seed cavities. Other seeds began to sprout within the pod itself while the pod was drying, rendering them useless for saving. But every so often, a straw-colored pod would crack open, and five or six beautifully purple, perfect seeds would tumble to the table, where they dried to their distinctive glossy black.

By season’s end, I had saved about half a cup of seeds. Undoubtedly due to the drought and heat they’d survived, some were odd-shaped, and others didn’t have the characteristic onyx-like luster that Allison’s seeds originally had, but I saved every one that looked like it might have a chance. If I saved them, year after year, they could adapt to my dry hill just as much as they once adapted to some Italian valley.

Origins

Now that I had grown these pole beans and successfully saved enough seeds for a bigger planting next spring, I knew I wanted to keep growing them every year. I was excited at the idea of the beans becoming part of my own family’s memories.

But as I thought about the most recent generation of “Grandma Gina” sitting in my seed box over the winter, I became keenly aware that Gina wasn’t my grandmother. Even though she was the first of her family to be born on American soil, my own Nonna didn’t have a garden of her own, and had passed along no seeds to me. I started wondering about the journey these seeds had gone on to somehow arrive in my dry Ozark garden. Who was Gina, anyway? Where had her seeds come from originally? How did they end up in New York?

It sounded like a good mystery to unravel.

I started with that beginning step of many a modern inquiry: searching for “Grandma Gina Bean” on the internet. This time, I did find a small seed company that had a listing for the seeds (they had been acquired from a bean collector in Poland), though they were “out of stock,” and no indication of ever coming back into stock. I found a gardening forum with some folks who saved rare bean varieties, but none of them actually grew most of the hundreds of beans in their collection. When I inquired about “Gina” someone said that they had it in their hoard, but had never grown it. Since I had grown them myself, it looked like I already knew more than they did.

As many a modern inquirer finds, the internet offers the illusion of answers, but often doesn’t actually deliver much. It was time to go back to real people. I contacted Allison in New York again, seeing if I could trace Grandma Gina through the people her seeds had touched. She said she had received the seeds from Remy Rotella of the Sample Seed Shop in New York, interest piqued by their unusually large size.

Finally, a trail to follow! An internet search revealed that Remy had passed away and the Sample Seed Shop no longer existed. Allison had retained Remy’s delightfully honest, original description of the bean from her now-defunct website, however, and passed it along to me.

“So I had beans from a trade with a beany friend in 2010, and I said I better grow these before they go bad. I had decent germination so I was happy and planted them and forgot. Well, I’m walking through my plantings and I see these ginormous beans and thought what the heck are those? I had to crawl around to find the tag. I had not been told in the trade that these beans grew like this, only that it was a flat Romano type. The bean seeds are spaced apart in the pods and are deep purple blue almost black. Some of the seed split in the pod and they are a bit late to make seed so growers in short season areas may have issues collecting seeds.”

Remy went on to detail the “beany friend’s” recollections of his own acquisition of the bean. He, however, had actually gotten the seeds from one of Grandma Gina’s actual granddaughters. He had told her where the granddaughters now lived, and that “Grandma Gina Lami brought the beans with her from Italy in the early 1900s. She grew them every year. Her granddaughters now carry the tradition.”

I thanked Allison for the information and spun meditatively in my computer chair. I had followed the bean from myself, to Allison, to Remy, to the mysterious “Beany Friend,” to the unnamed granddaughters, to Grandma Gina Lami herself more than 100 years ago. Now, I wasn’t sure what the best route was. I was intrigued by the idea of continuing to follow the bean’s trail to the family that first brought it stateside, to learn more about it from the Lami family directly, but I was hesitant to invade into someone else’s life. This wasn’t just asking a seed company about a shipment of impersonal product, but a treasured heirloom seed that had been stewarded for more than a hundred years by a grandmother and set of granddaughters. What’s more, it had escaped the taint of commercialization, and had come to me in the oldest and purest form of seed sharing — a seed traded for a seed, not sold for cold cash, not franchised, not trademarked.

The Italian Garden Project

Even though I had found their last name and the cities where the granddaughters currently lived, I was just unwilling to do what felt like creepily stalking the Lami family. I decided to go a different route and see if I could find records of this unusual type of bean back in Italy proper. I begrudgingly went back to Google and tried to employ all of my feeble Italian skills, searching for “fagolio nano” and seeing if anything came up that resembled my seeds.

A website came up called “The Italian Garden Project,” which was dedicated to finding family varieties of Italian-American seeds and preserving the memories and traditions of the immigrants who preserved them. And it was in English! Without expecting much, I filled out the online inquiry form, curious if anyone at the project had come across unusually large, black Roma beans in their own investigations.

To my great delight, within 24 hours I got a reply from the project’s actual founder, Mary Menniti. I was so glad to be talking to a human again, rather than the internet! She was intrigued. She’d never seen Roma beans of that size, and wanted to know more. I sent her photos of my own plants and all the information I had gathered so far. She then surprised me by revealing that she lived in the same city as one of the granddaughters, and would do some actual in-person research at the local Italian heritage museum to see what she could discover about the family.

Suddenly, the investigation had feet! Mary and I began sharing her discoveries through email. She found a name and a local address for one of the granddaughters. She talked with an old employer. She made some phone calls. She asked a lot of questions. And quicker than I thought possible, Mary was able to get in contact with Gina’s granddaughter, Suzan Lami, and, by proxy, Gina’s other granddaughter Leslie Lami Reed. They were warm, friendly, and oh-so-willing to talk about their grandparents’ gardening work. We finally gathered the whole story.

These beautiful beans have lovely magenta-ish flowers.

The Lami Family

Gina and Rugero Lami were raised in Palagano, Italy, a small hill town farming community. As newlyweds, they sailed for America in 1921, hoping to start a new life in New York. Rugero was a blacksmith in the coal mines at first, but eventually changed professions to opening an Italian import business in Pennsylvania. There they raised Nancy and Suzan’s father, as well as a garden, and a love for family and honest, homemade food that was passed on to their granddaughters.

Leslie wrote, “Here’s how Nonno grew the beans: In well fertilized soil (he occasionally had a pile of horse dung delivered to the house — hard to forget!) Nonno made a tripod from three poles about seven feet tall. Pound each leg into the ground. After the earth had warmed he placed three seeds at the base of each leg of the tripod. This was in case of seed failure. He had about six tripod units, and he grew a lot of beans! These beans will climb, much higher than six feet.

When Grandmother passed away, I think Suzan and I were going through the kitchen cabinets, and we found the bean seeds above the stove in the kitchen. We split the seeds between us, each of us hoping to see if we could grow the special and delicious beans that Nonna always served in the summer; steamed, cooled, and marinated in a drizzle of olive oil, salt, and chopped parsley.”

She also shared how to save the seeds — that while they would sometimes let the seeds dry on the vine, they also sometimes actually took the mature seeds out of the pod before the pod itself dried (this would stop the sprouting-in-pod problem I’d faced!) And finally, Suzan told me that she shares the beans with whoever she can. That includes when she shared seeds with an “heirloom seed guy” some 20 years ago, which must have been the step to allow the seeds to find their meandering way to me (perhaps he was Remy’s mysterious “Beany Friend?”).

Through writing back and forth with Suzan and Leslie I learned that they referred to their special beans in different ways — “Grandma Gina” beans, “LL Beans” (Leslie’s initials, and a funny pun) and, as Leslie wrote in her memories to me, “Lami beans.” The family name appealed to me. After all, Rugero was the one who grew them, Gina was the one who cooked them, and Leslie and Suzan were the ones who didn’t let them be forgotten. So I decided to call them “Lami beans,” but I kind of like that they don’t have a trademarked, registered moniker.

At last, I had as complete a chain as I could construct. Seeds in my own garden, that had come from Allison, from Remy, from the “Beany Friend,” from Suzan, from Rugero and Gina, from Palagano, Italy. Of course, that’s not the bean’s entire genealogy. Those beans, after all, were domesticated from Phaseolus vulgaris, a plant native to the Americas, and possibly first domesticated by indigenous farmers in the Andes Mountains, where it traveled from native garden to native garden, was probably picked up by Spanish explorers, and eventually made its way to Italy, where it was selected over time into its behemoth Roma-shape. I wonder how many Atlantic voyages the bean has made so far?

The truly miraculous thing is that these beans have existed purely by being passed hand-to-hand (or envelope), grown, saved, and shared for hundreds of years in an unbroken chain of seed savers that I feel honored to be a link in. It makes my seed box feel like a priceless treasure chest. But unlike cold gold and jewels that are hoarded and guarded jealously, I want others to have it, and, like Suzan, I have begun sharing these beans with others. This is a treasure that multiplies itself, and can be shared freely.

… For those willing to still grow it.

Author’s note: This article was a special one for me to write, and I couldn’t have brought it together without others’ gracious help. I think that’s a beautiful reflection of the spirit of seed-sharing. So I’ll end this with a special thank you to Allison Berg of Stillwater Valley Farms for her generosity, to Mary Menniti of the Italian Garden Project (theitaliangardenproject.com), for her friendly help and thorough investigation, to Suzan Lami, for sharing her precious beans 20 years ago and taking the time to kindly email an inquisitive stranger, to Leslie Lami Reed, for recording and sharing her memories, and to Rugero and Gina Lami, for cultivating a garden 100 years ago that has now touched my own family. D