By Massad Ayoob

Back in the mid-1990s, I got a call from a fella named Dave Duffy. He published a magazine called Backwoods Home, and was looking for a gun editor. I was a little embarrassed to have to tell him I’d never heard of the publication. He sent me some back issues and a current copy. I liked his and his family’s approach to self-sufficiency, and got back to him to say, basically, “Send me in, Coach!”

So, here I am, still on staff and Dave wants a bio. There’s a phrase from the Grateful Dead that my generation uses a lot: “What a long, strange trip it’s been.”

To start…

I’m from the second generation of my family born in this country. As best I can determine, my paternal grandparents came to the U.S. from Damascus in the last decade of the nineteenth century and settled in Boston, where my dad was born in the year 1900. My maternal grandfather immigrated here from Scotland after a sojourn in Canada and his wife, from County Cork, Ireland, in the first decade of the 20th Century. They too made their home in the Boston area, Dorchester, where my mom was born in 1909. My parents met there in the late ‘30s, and married in 1940. When World War II ended in 1945, they moved to southern New Hampshire, where I came along as a surprise change of life baby in 1948.

Why do I mention ethnicity? In my adult career as a writer and firearms instructor, I ran across the occasional person who would ask, “If you’re cool enough to teach me this stuff, how come you were never World Champion Combat Pistol Shooter?” My ancestors gave me the perfect answer: “It’s genetic. When you’re half Syrian, a quarter Irish, and a quarter Scottish, you’re three-quarters genetically programmed to shoot the hostage targets first. The penalties add up, and when your Scottish quarter asks for a refund on the entry fee, it starts to become embarrassing.”

My mom and her family were not “gun people.” In fact, my mother hated guns herself, but tolerated them because she understood their protective purpose. My father and his dad, however, were both armed citizens. Both were involved in successful self-defense shootings in the early 20th Century in Boston. My dad was a jeweler and watchmaker who had established his first store in 1932 in Boston, and so I grew up in an armed household and an armed family business.

Damn, I’ve gotten old…here in March 2020 with a 60-round demo target I shot for students at a MAG-40 class in Mississippi with a stock Glock 19 Gen5 9mm.

I came to shooting early. My dad was athletic, an extraordinary swimmer and a boxer in his youth. I had asthma from childhood, and the family doctor was adamant that athletics were out. Hell, I couldn’t even swim; perhaps because of buoyancy issues due to the asthma, I was a “natural sinker.” When Dad discovered that I liked guns, he was kinda like, “Thank God, there’s something masculine my only son can do,” so he indulged me in that regard. One of my earliest memories is him holding my older sister’s Stevens .22 rifle balanced on the palm of his hand as I climbed over the top of the stock that was too long for me to get to the shoulder, to aim and squeeze off shots. He told me later I was four years old when he started doing that. When Mom went shopping in the city, she’d drop me at the store for Dad to babysit, and to keep me occupied he’d put me in the back room with an unloaded Colt revolver to dry fire. At first, the double action trigger pull was more than I could handle, but I learned to press the hammer spur against a hard object to push the gun and cock it so I could “fire” it single action. That was my introduction to a rule of firearms safety I’ve shared ever since: we will never be able to childproof our guns, so we have to “gunproof” our children.

My generation grew up calling these “.45 automatics” instead of “semis.” Hell, that was the word stamped on the gun and the ammo box… (Pistol is Trapper Scorpion, a chopped and channeled Colt Combat Commander custom built by Lin Alexiou decades ago.)

My first gun of my very own was an Eastern Arms break-open single barrel 12-gauge shotgun, when I was about seven. Yes, it knocked me flat on my ass the first time I shot it. Dad started me live-fire on handguns at age nine, and at eleven, I got my first pistol of my very own, a second-hand Ruger Standard Model .22 autoloader he’d bought for $20. I loved that gun, but in the 1950s one was expected to shoot a pistol one-handed and it was just too heavy for a little guy just on the cusp of adolescence. We traded it for a new High Standard Sentinel .22 revolver with a light aluminum frame at the Western Auto store across the street from my dad’s jewelry store, and that was the gun I really learned to hit with.

Twelve was a pivotal age for me, and though I didn’t realize it at the time, a most formative one. By then I had my first centerfire handgun, a WWII souvenir Beretta 1934 model .380. I had discovered gun shops and gun magazines. At Sprague’s Gun Shop in Hooksett, NH, there were boxes of old issues of American Rifleman, Guns & Ammo, and Guns magazines that I could buy for a dime. It was in the pages of the late 1950s G&A that I found the work of Col. Jeff Cooper. I loved his writing: it was as if a Messiah had risen in the west. Cooper was the high priest of the Colt .45 automatic (yes, it was called “automatic” instead of “semi-automatic” back then, and it said “.45 Automatic” on the ammo boxes and the Colt pistol itself) and I asked my dad why he only carried a .38 caliber Colt Cobra. Having dropped two deadly assailants instantly with one shot apiece himself with round-nose lead .38 slugs, my father just smiled tolerantly, and perhaps a little bit smugly, but under the tree for my twelfth Christmas was a Colt 1911 .45 automatic.

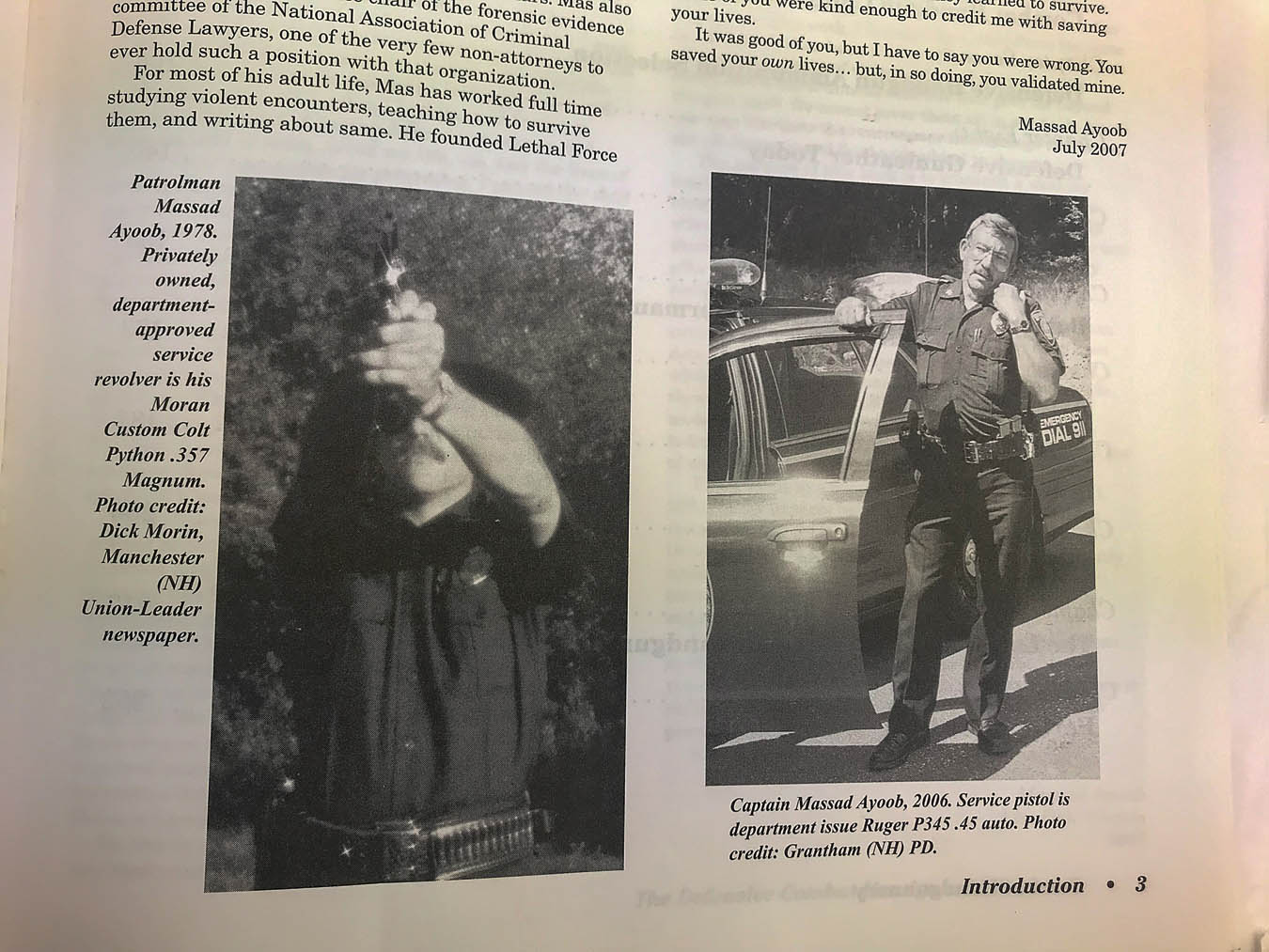

Through the mists of time, spanning 28 of 40+ years in LE. Service revolver at left is personally owned Colt Python .357 Magnum; issue duty .45 auto at right is Ruger P345.

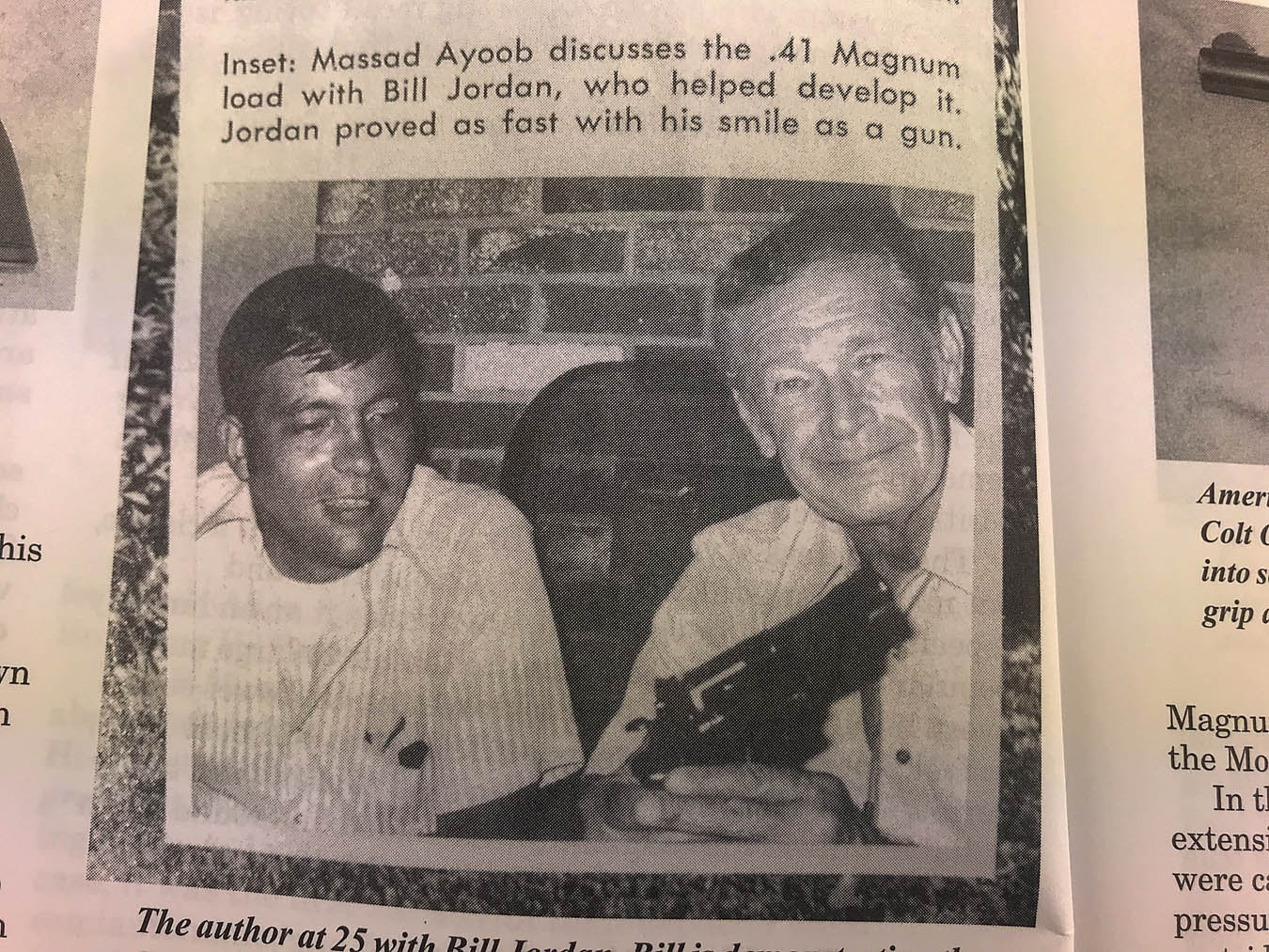

I was about 25 when I sat at the feet of the legendary Bill Jordan. Here he’s holding the S&W .41 Magnum he helped to bring into existence.

That was important, because at age twelve I was no longer the babysat kid in the back room with an empty revolver but was working in the store part time and summers. There were assorted pistols and revolvers stashed in tactical locations in that armed robbery-prone type of business, plus a Winchester Model 1897 12-gauge pump shotgun in the back room, all decidedly loaded, but Dad pointed out that when the crap hit the fan I might not be close enough to any of them, so if I was going to work there, I was going to carry. The gun I chose was that .45, cocked and locked and shoved inside the waistband behind my right hip, always concealed by one of the white lab coats that my father had chosen as the shop uniform.

This put me in an interesting situation. Picture that you are twelve years old, carrying a loaded pistol, and expected under certain exigent circumstances to shoot adult human beings to death with it, and it’s not a game. I was never the smartest kid in class, but thank God not the stupidest either, and I realized I needed to learn the rules quick. The jewelry store’s clientele included the Chief of Police, several attorneys, and one very patient judge, all of whom were kind enough to take time out of busy days to sit down with a twelve-year-old kid who had an unusual problem. The law in that time and place made it legal for someone my age to carry in a place of business open to the public, with the approval of the employer, so long as I didn’t step out on the sidewalk with a loaded gun. It taught me one of what would later become “Ayoob’s Laws:” “Don’t break the law. Know the law better than the other guy and you probably won’t feel a need to break it.”

Those visits sent me on a longer path, to legal libraries including the state library (we were located in the Capitol City), and I haunted that place. I am thankful for the patience of legal librarians, too.

The years rolled on. They brought me into police work, shooting competition, hunting in exotic places, courtrooms, gun factories, and more. If when I was in high school, someone had asked me what were the worst jobs I’d be assigned in Hell, I would have sincerely answered “A tie between being a teacher and being a cop.”

I ended up becoming both. Go figure.

Confluence of circumstances and careers

I became a teacher and a cop. I became a shooter and a hunter, an expert witness in the courts and even a trial advocate. I became a writer. Bear with me, and I’ll tell you how that all came together.

Writing

In school, writing was my one talent. (Well, that and researching so I knew what the hell I was writing about, which really is the core of meaningful writing in the first place.) In school, I wanted to be a writer when I grew up, but research showed me that only one in several thousand people would ever be able to support himself from writing, so I went to college with a business major for backup since I knew I was likely to inherit my dad’s jewelry store.

I’m a non-fiction writer. The fundamental rule of “write what you know” is absolutely true, and I’ve followed it all my life. A corollary to that is, experts in the field know more than you do, so go to them first. I did.

I had been a voracious reader of gun magazines since childhood, and in 1970 I read a glowing review of the Czech P38 pistol, a double action only .380 totally distinct from the trend-setting Walther with the same designation. I exploded in youthful fury: when I was about 14, I’d had one of those and a few rounds into the first shooting session, the firing pin retainer on this pistol manufactured by slave labor under the Nazis let go and sent the firing pin straight back, right on course to my eye. It would have skewered my eyeball from pupil to optic nerve like a cocktail toothpick through a martini olive had it not been stopped by my eyeglasses, which were broken in the incident. I wrote an angry letter to the editor, Ken Warner, of the magazine, GUNSport. Ken wrote me back politely acknowledging my concerns, and suggesting that if I thought I could write better articles, I should try. Thank you forever, Ken. George Sheldon, a gunsmith, lived near me and was doing something extraordinary at the time, cutting GI .45 automatics down to compact “Bobcat” size. My article on that appeared in the February 1971 edition of GUNSport, and my writing career was off and running.

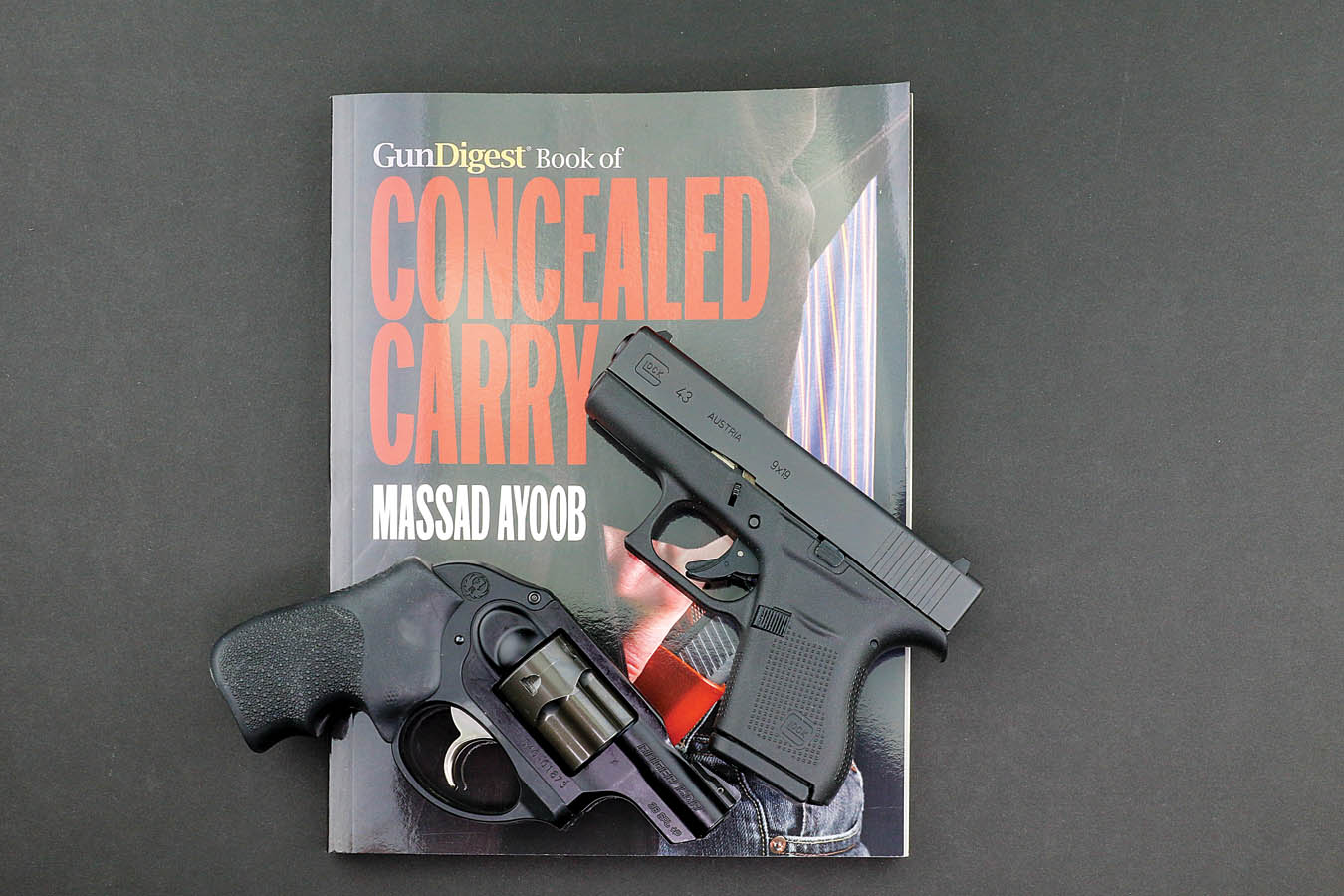

Managed to get a few books published along the way… the guns are 9mm Glock 43 and .38 Special Ruger LCR.

In 1972, editor Jean LaVallee gave me my first masthead position, as gun editor of his monthly New Hampshire Outdoorsman. I focused mainly on hunting, shooting sports … and gun legislation. New Hampshire’s first in the nation Presidential primary gave all of us there an opportunity to meet the candidates in person, and writer status gave me one-on-one interviews. The first politician to lie to me to my face (but certainly not the last) was George McGovern in 1972, shortly before he won the Democrats’ nomination. After asking me where our magazine stood on “gun control,” he told me for the record that he thought we didn’t need any more, we just needed to enforce the laws already on the books. A month later he told Look magazine that he would push for national firearms registration. I rejoiced when he was crushed by the Nixon re-election landslide.

I’m gonna have to jump back and forth on the timeline for a bit here, because some things inter-related. In the early 1970s I got into police work and particularly law enforcement officer (LEO) training. Following the eternal advice to writers, “write what you know,” I started contributing to police professional journals. Along about 1974, I was contacted by a publisher who produced a series of regional magazines in the field. The editor, Bob Boris, told me they’d read my stuff in the national police magazine Law and Order and he had a proposal. Most cops knew their stuff but didn’t write well, he said, while the professional writers didn’t understand police work and their LEO readers hated that. He needed a cop who could write, and his offer was this: “We give you the title of Feature Editor. We fly you all over the country to debrief the instructors and chiefs of major departments on the fine points of what policies and equipment they’ve chosen, and how they’ve worked out in the field, and tell the stories of hero cops who won gunfights and that sort of thing. We’ll pay you more than your chief of police makes.”

Well, I agonized over that for about a second or so, and jumped on it. That led to several years of traveling the country, from NYPD to LAPD to points in between and accumulating a lot of inside knowledge I was able to share with people who needed to know it. The editors of the various police magazines knew most of their readers would never be funded by their department to take a week-long course at Federal Law Enforcement Training Center or Smith & Wesson Academy … but the magazine could send me to take the course and distill the most important lessons for police readers. As a department instructor, I would have been lucky to get sent to a school once every year or two, but in the police writer capacity, there was a while when I was attending one a month. It got me training I would have needed several separate careers to accumulate had I done it as a cop instead of as a writer. All of that went into the reservoir of accumulated knowledge and collective experience from which I would later teach.

I’ve gotten to become friends some giants in the business along the way. That’s John Farnam in the center and Ken Hackathorn on the right.

I had graduated college in 1970 with an associate’s degree on the accounting curriculum and a bachelor’s in business management. I worked in the jewelry store for a while and then got a job as assistant treasurer for the New Hampshire Department of Employment Security. I was essentially a glorified accountant, and I loved the people I worked with but hated the work itself. It was during that period I became a part-time cop.

I was also writing. I wanted to be a freelance writer but research showed me that fewer than five thousand people were able to make a living at that. I loved writing. I loved police patrol too, but at the time it was a poorly paid profession. At 23 I married my high school sweetheart, and realized that now, before we had kids, was the time I could risk the big decision. I resigned from the state, kept the part-time police job, and became a full-time freelance writer. It worked, in large part thanks to that Feature Editor assignment, and I did that for about a decade. I found myself writing for more magazines, and in 1978 my first book was published by Charles Thomas, the leading publisher of police training manuals. It was titled “Fundamentals of Modern Police Impact Weapons.” I had met the great police/gun writer Bill Jordan and we had become friends. He was kind enough to write the foreword.

In the Gravest Extreme

In the meantime, I had written a manuscript titled “In the Gravest Extreme: the Role of the Firearm in Personal Protection.” When I’d been a kid in the state legal library researching deadly force because I was probably the only person my age in the state to carry a gun at work, I remember thinking “Somebody ought to write a book about this side of it! And when I grow up if nobody has, maybe I will!” Well, by then nobody had, so I did. Stoeger, the publishers of the annual Gun Bible, were interested but then told me, “We don’t think our readers want a book telling them they can’t just kill people in self-defense and get away with it,” or words to that effect. Another company signed a contract for the book, then reneged on the same grounds. I told them they were violating their own contract. They said, “Sue us.” I couldn’t afford to then.

Back to Bill Jordan. When I met him in 1974 and asked him to autograph my copy of his book about gunfighting aptly titled “No Second Place Winner,” I asked him who had published it, since my copy had no publisher’s imprimatur. He replied, “Oh, ah had a printer in Shreveport put it together for me.” My face must have betrayed my surprise, because he then added, “Ah know what you’re gonna say. ‘Vanity press, vanity press.’ Well, boy, stop an’ think: you should know your topic better than the publisher. Why should y’all settle for ten percent of what they say they sold, when y’all can have it all?”

No one ever gave me better advice on anything. In 1980 my wife and I scraped up the money to print and bind a few thousand copies. It helped that GUNS magazine paid to serialize pre-publication chapters. We ended up selling a six-figure book count. We established Police Bookshelf to do it, and that publishing company later produced John Farnam’s first book and many more. It still sells “In the Gravest Extreme” today. We hired employees and were off and running. My lovely bride ran that business while I ran around the country doing research, shooting matches, doing police work when I was at home, and having just a helluva time. In the late 1970s I followed Jan Stevenson and George Nonte as handgun editor of GUNS magazine, where I still write the handgun column. Counting second editions, I wound up writing 20 or so books, including one for the world’s largest publisher (“The Truth About Self-Protection” published by Bantam, now available from Police Bookshelf) and several for the Gun Digest company.

Police work

I started shooting competition in my mid-teens at turkey shoots, informal gatherings where, at least in NH, you shot at standing and running deer targets with hunting rifles and, if you were top shot on your relay, won a frozen Butterball turkey to take home. There were side matches for pistol and shotgun. When I was 19 my friend Nolan Santy, master gunsmith extraordinaire, got me into conventional bulls-eye pistol shooting. I qualified Expert my first time out in the Indoor format and Sharpshooter outdoors (and stagnated there; I never did make Master in that discipline, dammit). Nolan was also a part-time cop, and in 1972 he told me about PPC shooting: all different positions, rapid fire, speed reloading, and shooting from 7 to 15 yards. But you had to be a cop to do it. A few of us got together and approached the head of the Civil Defense Auxiliary Police in a small department, and told him that if he gave us badges, we could pretty much guarantee his department would have State Champion Police Pistol Team in a year. The head of the unit said yeah, fine, but he didn’t need target shooters: he needed cops; we’d have to take training and actually go out there and do the job. I remember saying, “Hey, it’ll be fun.” The deal was sealed.

My last day as a cop, 6/10/17. Chief Walter Madore gives me my send-off on retirement. Walt retired not long after me – a good chief.

My first night on ride-along was like, “To hell with shooting, where has this been all my life?” It had little to do with the power of it: the irresistible challenge was the responsibility. I quickly got upgraded from Auxiliary Police to what was called then Special Officer, fully sworn and patrolling on my own. In my first year, I arrested a 16-year-old kid I caught burglarizing a junkyard for auto parts. He told me remorsefully that he couldn’t afford the parts to fix his old jalopy. It was his first offense. His dad begged, “Is there any way I can keep my kid from getting a criminal record?” I talked with the owner of the junkyard who railed about punk kids stealing him blind, and he “wanted the little bastard sent to the reformatory.” I asked the owner how many people he employed, and he answered, “None. I can’t afford employees.” So, I brokered a deal: the dad would sign a waiver of speedy trial for the juvenile, on the condition that the kid would work for free for the junkyard owner for the summer. At the end of summer, I went back to the owner, who told me the kid had worked out so well he was going to keep him on part time and pay him during the school year. We dropped charges. I kept track: the boy stayed on the straight and narrow.

It taught me what “street justice” really is, and it isn’t something that’s administered with the non-illuminating end of a large black flashlight. “Officer discretion” is important.

Because I had been published as a gun writer and was seen as a gun expert, I became department firearms instructor early on. Training was part of my police career all the way through. I did eight years as a patrolman with that department, two years as sergeant and six as lieutenant on the second, and 27 years as captain on the third agency. That brought me to 2017. My upcoming 69th birthday saw me looking in the mirror and just not seeing a cop anymore, so I retired. I enjoyed the hell out of most of those 43 years. Police work is like the practice of medicine: when you go home at night, you know you did something good for somebody that day at work.

Teaching

Instructing became my main career. We had fulfilled that promise to the department to give them the State Champion Police Pistol Team, and my buddy Rich Brown had won the individual State Championship for the department as well. The following year, 1974, I won it. (Rich won it back again the next year, though.) Largely on the strength of winning my first state championship at the age of 25, I was invited to come on board as assistant professor in the police science program at the NH Vocational-Technical Institute in Nashua, teaching weapons and chemical agents. Becoming an instructor on my own department had sent me on a crash-course odyssey to every top-ranked police instructor course I could find, such as the Smith & Wesson Academy, and writing for the police magazines had given me access to training at NYPD and several other bellwether agencies. All that went into the curriculum I taught, and I got good reviews. It turned out I had a knack for it.

In 1980, I was invited to become director of firearms training for the Defensive Tactics Institute, and taught for them around the country. That lasted for a year and a half, because my training career had taken an interesting turn.

Teaching is what I do for a living, and have since 1982.

In 1978 when I was competing at the US National Championships of the International Practical Shooting Confederation, I met one of my idols, Ray Chapman, the first World Champion of the Combat Handgun. Ray took me under his wing, later writing the foreword for my book “StressFire.” When “Gravest Extreme” came out in 1980 Ray read it and told me, “I teach the ‘how.’ You’re teaching the ‘when.’ How about you and I get together and teach a course at my school on ‘How and When To Shoot?’” We did that in the spring of ’81 at Ray’s Chapman Academy in Columbia, Missouri. It was a hit, getting on ABC’s “20/20,” and Ray told me, “You ought to open your own school.” I talked it over with my wife. We figured it would be something I could do on home turf and take away from all the time I was spending on the road researching for books and articles. We incorporated Lethal Force Institute and did our first LFI class in October 1981. Demand burgeoned. Within a year LFI became the tail that wagged the dog. I was now a full-time instructor, part-time cop and writer and everything else. It was easier to take me to 20 or 30 students where they were than to bring them to me, so I was now ironically on the road even more.

Unfortunately this made me also a part-time husband. After 30 years of marriage, my wife and I had developed different visions of the future. We amicably divorced in 2002. She took the publishing and sales side of what had grown into multiple companies, I took the writing and expert testimony side, and we jointly directed the school until 2009. She was ready to retire, I wasn’t, so I left LFI and started Massad Ayoob Group, which is my primary job today, teaching around the country along with staff all over the place. (http://massadayoobgroup.com.)

I’ve gotten lucky at a few shooting matches over the years. Here, in 2011, I’ve just had the privilege of winning the ILEETA Cup.

Court side

I did my first case as an expert witness in 1979 and have been doing it ever since, focusing on weapons, training standards, and dynamics of violent encounters. Along the way, because my state was one of four with “police prosecutors” who prosecute misdemeanors and violations without the aid of law school graduate attorneys, I became one of those too. The drama of the courts gives you your daily adrenaline requirement: when you’re doing a death penalty case for the defense and you know the evidence shows the defendant is innocent, you literally have a life in your hands, just as in police work. It taught me a lot about trial tactics. The saying among attorneys is “law school teaches you the law, but trial tactics is something you learn on the job or in CLE (Continuing Legal Education for practicing lawyers).” I accumulated enough knowledge and experience that I taught Courtroom Testimony for Police Instructors in various law enforcement training venues, and management of deadly force cases in CLE settings. I wound up doing two terms as Co-Vice Chair of the Forensic Evidence Committee for the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers and a few years on the curriculum committee for the annual Firearms Law Seminar for the State Bar of Texas. A few people sneered and said “Prosecutor and defense witness? Working both sides of the street, huh?” My answer has always been, “Justice is a two-way street. If you only go one way on a two-way street, you’ll only see half of what’s going on, and you’ll eventually end up traveling in circles.” I still do the expert witness thing, and 40 years of it has taught me a lot to pass on to good people who work on all sides of the system.

I’ve been an expert witness for the courts in weapons and homicide cases since 1979, here testifying for the defense in a Montana homicide trial in 2016. The defendant is now a free man. Photo from helenair.com.

Some of that testimony has been in relation to cases challenging Draconian anti-gun laws, including the occasional friend of the court brief in cases including Heller v. District of Columbia. I had become an NRA member in my teens, a life member as soon as I could afford it, and a benefactor member later. I joined the Second Amendment Foundation in the late 1970s and have proudly served for many years on that organization’s Board of Trustees.

And that’s about it. I’ve had a long, instructive, fun ride, complete with lights and sirens at times. My two daughters grew up to be the people others in their lives rely upon in times of trouble, and that has made me more proud of them than all of their many other accomplishments. I have two fine sons-in-law whom I constantly pray for (because if anything happens to them I’ll never find anyone else who can handle my daughters), four wonderful grandchildren on my side and more plus a couple of great-grandkids on the side of my now-wife Gail, a self-styled shooter-chick with several state and regional handgun championships on her own resume. Ours was an open carry wedding in Chicagoland, which allowed us to raise a middle finger to the anti-gunners. Gail Pepin is the producer-editor (ergo, “PrEditor) of the Pro Arms Podcast at www.proarmspodcast.com. We travel together to classes and matches. Life is good.

Back at Backwoods Home, I enjoy writing for this publication because while I’ve always done specialist stuff for the gun magazines and the police professional journals, it gives me a venue to write for the general public. I know that we have everything from genuine gun experts to people who’ve never touched a gun reading Backwoods Home, and it’s a challenge to write something for each issue that will hopefully be useful for that entire spectrum. All of you reading this are welcome to join me at my blog at www.backwoodshome.com/blogs/massadayoob.

Be safe, and thanks for reading.

I saw Mas on FRONTLINE (when it was a honest show) in 1982(?) And decided that since I had owned a pistol since my civil rights worker days in the ’60s, I (a lawyer) should know the when of self-defense. And a summer vacation in New Hampshire sounded nice.

Wow, what a course. Mas taught me not only when but how. It was the best week of my life.

I went on to IPSC competition (never great) and took courses from Chapman and Cooper as well as advanced LFI courses. Then Patrick Purdy shot up a schoolyard and I became the pro-gun lobbyist in my state. I wrote our CCW Reform law in 2003 with my training from Mas at the front of my mind.

I even took a Self-Defense for Lawyers course from him 5 years ago.

Mas is, in my opinion, the best trainer in America (and I’ve seen many) and a real jewel of a guy (no pun intended).

Mas,

Wow! Thank you for sharing this with us; neat stuff & interesting! I remember jumping at the chance to take LFI-1 in Sacramento in ‘94; you were the only instructor I knew of, who was really teaching the “when”. And doing so in a way that reached us and stuck. What I learned then has stayed with & helped me since, including my 28 years as a cop. Watching you during that class imparted a favorable impression of you personally & professionally – the years since have added to that initial evaluation.

Very good, congratulations, and our best.

I know you’ve helped a lot of good decent people, Thank You.

PS: those helicopters can’t be trusted – watch out for them!

We met at a NRA Firearms Law Seminar in Atlanta. I’d been a criminal ( aren’t we all) defense attorney since 1977. What you told me about how to interact with the police after a shooting incident completely changed the advice I’ve given to hundreds of Michigan CPL class students since that date. Sorry about stealing your advice. The royalty check is in the mail…….

Thank you.

Happy Birthday Mas.

You’re a true treasure and wealth of knowledge. I feel very blessed to have taken your LFI class and if circumstances permit you will see me in a future class.

Vince

Mas, you are a national treasure! Always a good read! I have directed many others to your course since I took MAG 40. It was one if the highlights of my life. Very glad I availed myself if the opportunity to learn from the best. Stay safe!

I thoroughly enjoyed this bio, Mas. I’ve been a disciple for many years and I have received the benefit of both your writing and teaching talents. Many thanks and I hope many more years of a rewarding life.

It’s interesting for me to read you discuss your heroes. Did you know along the way you’ve become one yourself? That was a great read. Happy Birthday, and I wish you many more.

I just turned 65 and I fell like I have grown up with you Massad. I have been reading your stuff since the 80’s. Thanks for all you do and teach. Not much we can trust these days but I know one thing, if you say it, I trust it. Keep it up!

Happy Birthday Mas and Many More! You really are a blessed man! As your student and later assistant instructor I became a much better LEO over 25 years.

I learned so much from you that carried me through!

“I’m a non-fiction writer.”

With the exception of the very entertaining _Stakeout Squad_ series.

I bought In the Gravest Extreme when I became an NRA Personal Defense Instructor, and it made me a lot more valuable to my clients. This was a wonderful article, thank you for your contribution to the justice system. Being a LEO is challenging enough for most of us, but you took the profession to a level few others have managed to do.