By Don Lewis

The year was 1834, a year that didn’t really stand out as all that particularly important in American history. But like any other year, it had its share of firsts. The first railroad tunnel was completed in Pennsylvania and the United States Senate censured President Jackson for taking federal deposits from the bank of the U.S. In 1834, sandpaper and the hard-hat diving suit were patented, as was the first mechanical reaper. Congress created the Indian Territory in what was later to become the state of Oklahoma. A young lawyer by the name of Abraham Lincoln was elected to the Illinois State Legislature.

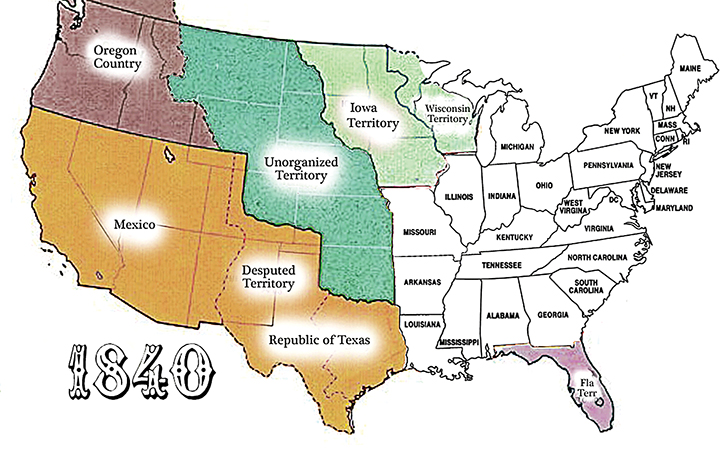

And in 1834, a merchant from New England named Nathaniel Wyeth and an Episcopalian missionary named Jason Lee led 80 people from Missouri to Oregon. They became the first group of settlers to make the 2,170-mile trip along what would soon thereafter become known as the Oregon Trail.

While they may have been the first, they certainly weren’t the last. By the end of the 1860s, an estimated 500,000 pioneers had traveled overland from the settled East to the uncertain West in search of a new life, new land, and golden treasure. To make the journey, these pioneers gave up nearly everything they possessed, left behind family and friends they might never see again, and walked across half a continent through seemingly endless prairie, high deserts, and snow-covered mountains. On the journey, they would pass through territories that would later become Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho, and Oregon.

Not all those who started the journey completed it. By some estimates, as many as 10 percent of travelers died en route, usually from disease or accidents. Some of those who wrote about the Oregon Trail and its ancillary branches declared it the longest cemetery in the world. Considering the number of deaths on the trail, an even spacing would create a grave every 50 yards, stretching from the Missouri River to Oregon City.

So who were these crazy people, and why did they place their lives and fortunes in jeopardy to reach a land none of them had ever seen?

The rationale of pioneers

The emigrants who kept journals of their travels gave many reasons for making the journey. Some were escaping frequent outbreaks of diseases like malaria and dysentery in the crowded Eastern states. Many were the children of pioneers who themselves had homesteaded in Indiana, Illinois, and the Michigan territories. These “youngsters” were forced to move further west because all the best river-bottom land for farming had already been claimed, and the competition for even the less-desirable farmland was growing. In 1830, the U.S. Census determined the population of the settled U.S. was nearly 13 million. By 1840, that population had grown to more than 17 million — an increase of almost 33 percent.

Estimates based on the preserved diaries of the travelers suggest as many as 70 percent of the Western immigrants were farmers by trade. Based on history and experience, many of these farmers realized that sooner or later the U.S. Congress would get around to ceding land in the Western territories to settlers. In 1850, Congress did just that — granting a square mile of land to each married couple. The travelers knew those who got there soonest would get the best land. And those who married and had children would get a lot of it.

“… there was much talk and excitement over the news of the great gold discoveries in California — and equally there was much talk concerning the wonderful fertile valleys of Oregon Territory — an act of Congress giving to actual settlers 640 acres of land. My father, John Tucker Scott, with much of the pioneer spirit in his blood, became so interested that he decided to ‘Go West.’” — Harriet Scott Palmer, 1852

There were other reasons for migrating. In 1849, many folks began the journey as “49ers,” heading for the newly-discovered gold fields of the Sierra foothills of California. Others who left the East for the West in the 1860s did so to escape the looming Civil War. But no matter the reason, there was one underlying sentiment shared by nearly every pioneer: the concept of Manifest Destiny, a belief that the growth of the United States was divinely preordained.

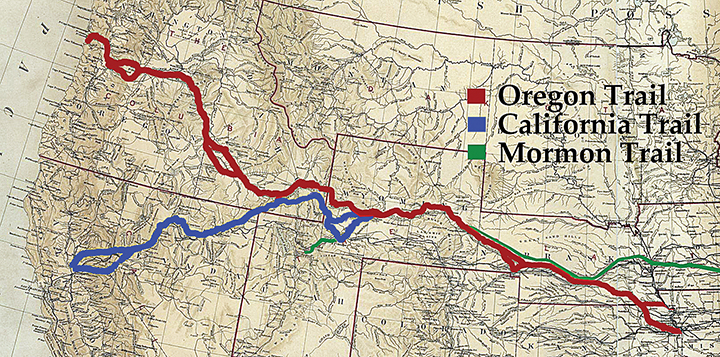

The trail

With a few exceptions, all the major Western emigrant trails started in the vicinity of the (aptly-named) frontier town of Independence, Missouri. From Independence or at various branches further to the west, the traveler could head southwest on the Santa Fe Trail, west to Sacramento on the California Trail, or continue northwest to Oregon. The Mormon Trail, which lead to Salt Lake City, began in the town of Nauvoo, Illinois and crossed the Missouri river north of Independence at Council Bluff, eventually joining up with the Oregon Trail near Fort Laramie, Wyoming.

The timing of departure from Independence was critical. Sufficiently available grass for the livestock meant leaving no earlier than mid-April. But leaving too late meant the possibility of encountering fall snows in the mountains — a June departure might well end in disaster. But leaving in the spring meant encountering rivers swollen with melt waters, violent spring prairie thunderstorms, and blistering mid-summer heat while crossing the deserts of southern Wyoming, Idaho, and eastern Oregon.

Going around the Horn

Not everyone with a hankering to reach the West traveled by trail. The very first immigrants to Oregon from the United States came by ship around Cape Horn or by sailing to Panama, crossing the isthmus to the Pacific side, and then taking another ship north.

But making the ocean journey was not a popular choice for most of the pioneers. For one thing, traveling to the West Coast by sea was expensive. In 1849, a single fare in cabin space from New York to San Francisco could cost over $500. For a few hundred dollars more, a family of four could be completely (if sparsely) equipped for the journey by trail and arrive there with enough tools and supplies to begin a homestead. Additionally, the voyage by sea had its own dangers and might take as long as a year to complete, far longer than the four to six months usually required to reach the Oregon territories by wagon.

The preparation

Guidebooks

The first thing any potential Westerner acquired were copies of the dozens of travel guidebooks that came out shortly after the Oregon Trail was opened. The Emmigrant’s Guide to Oregon and California, written by Lansford Hastings, was one of the earliest and most popular. But all of the travel guides — which varied considerably in quality — still provided commonly-known details on many of the same things: travel distances, river crossings, relatively current costs of food and equipment, warnings of potentially dangerous situations, and other important locality-related information.

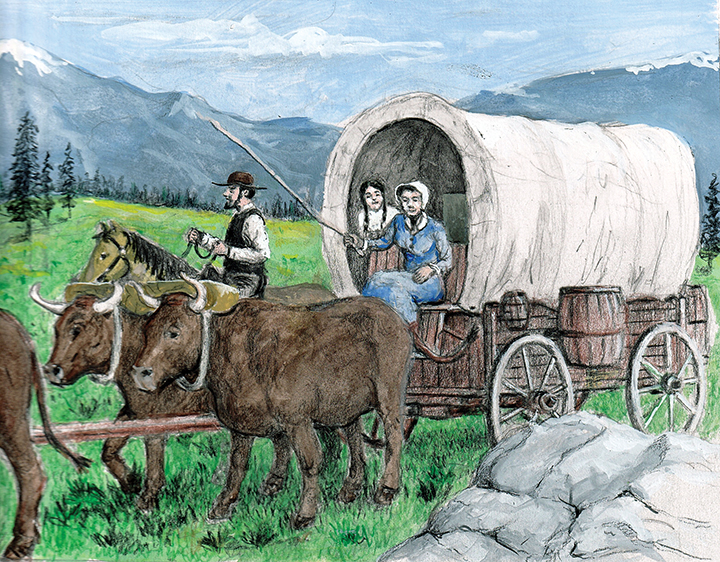

Many of the guidebooks also instructed potential trail travelers in the specific amounts and types of supplies that they would need to make the journey safely, as well as the most efficient wagon designs and the best draft animals for a successful wagon journey. Oxen were much preferred over horses or mules by experienced travelers.

“We fully tested the ox and mule teams, and we found the ox teams greatly superior. One ox will pull as much as two mules, and, in mud, as much as four. They are more easily managed, are not so subject to be lost or broken down on the way, cost less at the start, and are worth four times as much [in Oregon]…” — Peter Hardeman Burnett, pioneer and first Governor of California, 1843

There was another major advantage in using oxen over any other draft animals. In the end, and if absolutely necessary, you could always eat the ox.

Wagons

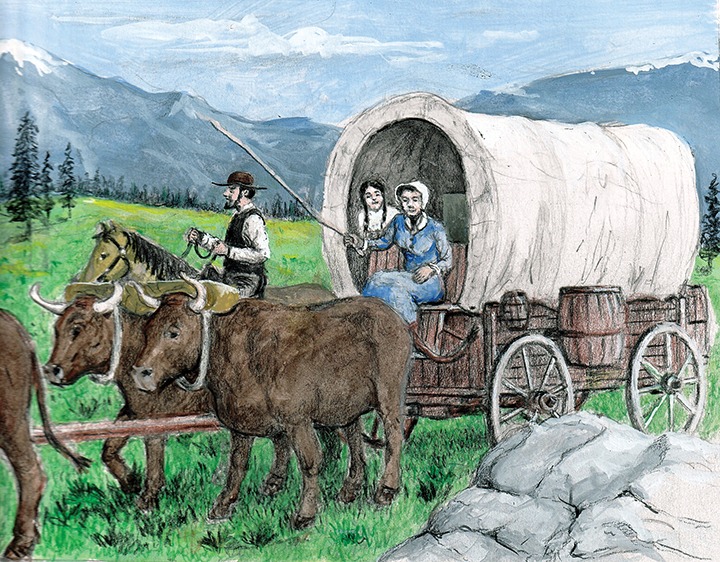

Most of the Western movies we watched as kids showed pioneer families perched on a seat high at the front end of a large, slope-sided wagon; Dad and Mom singing frontier songs with the kids in the back, all part of a long train of similar wagons. But the wagons used in those movies shared little in common with the wagons that traveled the Oregon Trail. Those movie wagons were Conestoga wagons, large freight-moving vessels that were far too heavy and unwieldy for navigating open prairie, muddy river crossings, and mountain passes.

The most common wagon used by the pioneers was the “prairie schooner.” On average, a prairie schooner was four feet wide and ten feet long. They had vertical or slightly canted sides with waterproofed canvas covers supported by bent-wood ribbing. The typical prairie schooner was capable of carrying a maximum of 2,500 pounds of supplies.

Prairie schooners were built light and strong, and the boxes were often waterproofed so they could be used as a temporary barge to float across rivers and streams too deep to ford. Because the wagons were so heavily laden, adding the additional weight of passengers was unwise. Rather than ride, it was far more likely that the family walked alongside, guiding the oxen. The only riders were usually those too ill to walk. Riding in the wagons was simply too dusty, too rough, and too hard on the livestock.

Occasionally, a wagon might be set up in such a way that the family could sleep inside at night with a temporary board floor and bedding placed over the supplies; but most of the pioneers used tents for passing the night, or slept under the stars. Storage space was far more important than living space.

A complete wagon, three yoke of oxen (meaning two oxen to a yoke, or six in total), food for a family of five, appropriate clothing, tools, and firearms could be acquired for a minimum of $600 (the equivalent of $15,000 today). But $600 was a small fortune to many of the cash-poor farmers preparing to make the journey.

“During that this fall, father began to make his arrangements to start the next spring for Oregon, but he had to find a buyer for his farm before he could leave, he asked fifteen hundred dollars for all his land, by Christmas he offered it for twelve hundred and about the middle of March he sold it to a Mr. Pemberton for eight hundred dollars, he said, he could not think of staying in that sickly country another summer.” — Abraham Henry Garrison, 1846

For those who were determined to make the trip west but did not have the necessary funds, one option was to accept loans or gifts from family and friends. Another option often used by bankrupt farmers was to sell “subscriptions” (a share of future profits from the new farm in the west) to their creditors, who had little chance of recovering the debts owed to them in any other way. For the truly destitute, another option was to hire on with other more prosperous pioneers as trail helpers in exchange for food and transportation.

Food on the Oregon Trail

Joel Palmer, a pioneer who made his first trip west in 1845, wrote a popular travel guide titled Journal of Travels Over the Rocky Mountains in 1847. In it, he recommended the following list of supplies for each adult: “…Two hundred pounds of flour, thirty pounds of pilot bread, seventy-five pounds of bacon, ten pounds of rice, five pounds of coffee, two pounds of tea, twenty-five pounds of sugar, half a bushel of dried beans, one bushel of dried fruit, two pounds of saleratus, ten pounds of salt, half a bushel of corn meal; and it is well to have half a bushel of corn, parched and ground; a small keg of vinegar should also be taken.”

While other guides varied to some degree in weight-per-item suggestions, Mr. Palmer’s recommendations were pretty typical.

Flour

Flour was always first on everyone’s list. But flour in the 19th century was not the bleached and enriched flour available today. In the mid-1800s, the trail pioneer had to choose between three types of flour: shorts, middlings, and superfine.

“Shorts” was a coarse-ground flour somewhere between wheat bran and whole wheat. It was poorly sifted and retained a high degree of impurities. Shorts flour was often the least-expensive option and varied considerably in quality, depending on the mill.

“Middlings” flour was a remainder product formed during the separation of bran from white flour. It was very high in gluten. In the separation process, middlings became a waste product for many mills and were often sold by those mills as inexpensive flour without further refinement.

“Superfine” flour was as close to modern white flour as was possible for the mid-19th-century mills to produce. It wasn’t all that white, but it was a far better quality of wheat than other options. It was often recommended for desserts such as cakes and pastries. It was also considerably more expensive than shorts or middlings.

Baking bread was a daily necessity on the trail. Whether you were baking in small sheet-iron ovens, Dutch ovens, or frying biscuits on a skillet, finding the necessary materials to make a fire — especially on the large stretches of prairie — was problematic. Carrying large amounts of firewood was simply not possible. Fortunately, there was (at least in the early years) a ready source of fuel during much of the journey: millions of small piles of dried buffalo “chips” that littered the plains. When stopping for a meal or for the night, an evening chore for children was to collect the chips. Buffalo dung made a surprisingly steady-burning and low-odor fire for baking or frying. When the chips were in short supply, the pioneers discovered that sage brush burned quite hot, although it added a certain flavor to the meal.

“Often we had to cook with grease wood or sagebrush. We had iron pots and teakettles for cooking, and did our baking in a Dutch oven with coals under it and over it. It was difficult for my Mother and sisters to work and cook this way, as we had been used to a large house, a cook stove and brick oven, and a maid to do the hard work.” — Sarah Bird Sprenger, 1852

Saleratus

Any bakers reading this might notice Palmer’s guide made no mention of yeast. There’s a simple explanation for this: no commercially-available yeast of the time could survive the trail.

Bread yeasts in the mid-19th century were caked or “wet” yeasts available in large part from beer breweries. Caked yeasts of that time simply had no shelf life, and needed to be used within days of delivery to the bakers. The only way to extend their longevity was to keep them refrigerated at temperatures below 45° F, which was impossible to do in a wagon on the hot plains.

Sourdough starter was also available to the pioneers, but it had its own problems. While more robust than baker’s yeast, it required time — sometimes a great deal of time — to make bread rise. Additionally, rising breads and pastries require a stable platform to avoid “falling,” an impossible condition in a jolting and shaking wagon.

The answer to this lack of leavening was saleratus (a precursor to our modern baking soda), which was discovered by chemists in the late 1700s. Saleratus was a form of bicarbonate of soda that, when enfolded in the dough for baked or fried bread, released carbon dioxide upon heating, causing the bread to rise.

While the initial saleratus carried by the prairie travelers came from chemists, the pioneers quickly found a natural source providentially located along the Oregon Trail near Independence Rock, Wyoming.

Only a few miles from the Sweetwater River, pioneers discovered a number of small lakes with no natural outflow, where mineral salts washed down from the nearby mountains were concentrated by evaporation, leaving hard white crusts of nearly pure saleratus. With the pioneer practice of prosaic place-naming, the largest of these bodies of water became known as Saleratus Lake, a name it still bears today.

“Fortunately, a young man from the valley, who had come out to meet friends, came past. He had a little flour to spare, which he gave us, with a tinful of rice, for which he would take nothing. We were very thankful for it, but we had neither salt nor saleratus, nor anything to bake in. Mr. H. went to a camp near and got a little of each with a skillet to bake in. I made up the dough, kneaded it in a cloth and baked it. It looks good, for all it had nothing but water, salt and saleratus in it.” — Esther Belle Hanna, 1852

Bacon

The other staple of trail life was bacon. In fact, the most common meal on the Oregon Trail was bacon and bread. As one pioneer dryly put it: “But then one does like a change and about the only change we have from bread and bacon is, bacon and bread.” — Helen Carpenter, 1857

As with flour, the bacon of the mid-1800s was not the bacon of today’s modern meat departments. Back then, “bacon” was defined as any pig meat from the sides, hams, or shoulders that had received a salt-cure. Despite its inclusion in practically every travel guide, bacon rarely made it through the entire journey because of its high fat content. As one waggish traveler put it: “It began to exhibit more signs of life than we had bargained for. It became necessary to scrape and smoke it, in order to get rid of its tendency to walk in insect form.”

Less “mobile” bacon could often be purchased along the trail at the various forts, or from entrepreneurial traveling vendors, at much higher prices. Unlike salt pork or beef (which was kept barreled in a brine solution), bacon was stored dry in bug-proof bags or boxes. In hot climates, bacon was buried in bran, which supposedly kept the fat from melting (or at least absorbed it).

Corn

Parched corn (corn whose kernels had been sun-dried or roasted in an oven) was very popular with the pioneers, if for no other reason than because it did not spoil easily. It was usually ground into a rough flour and cooked as a mush, which was served with milk from the traveler’s cows.

Desiccated or dried vegetables

Dried fruits were a staple, not only amongst the pioneers, but for practically everyone in 19th century America. But dried vegetables were initially less common in the larders of the pioneers.

That changed upon the publication of Randolph Marcy’s The Prairie Traveler: A Handbook for Overland Expeditions in 1859. Marcy suggested each traveler should avail themselves of a product used extensively in the Crimean War called “desiccated vegetables.”

Marcy wrote of how these vegetables were made: “They are prepared by cutting the fresh vegetables into thin slices and subjecting them to a very powerful press, which removes the juice and leaves a solid cake, which, after having been thoroughly dried in an oven becomes almost as hard as a rock. A small piece of this about half the size of a man’s hand, when boiled, swells up so as to fill a vegetable dish, and is sufficient for four men.” Depending on the source, the vegetables in question were a mixture of potatoes, cabbage, turnip, carrots, parsnips, beets, tomatoes, onions, peas, beans, lentils, and celery.

While many raved about the quality of these primitive dehydrated vegetables, others were less impressed. A member of the Third Iowa Cavalry Regiment wrote, “We have boiled, baked, fried, stewed, pickled, sweetened, salted it and tried it in puddings, cakes and pies; but it sets all modes of cooking in defiance, so the boys break it up and smoke it in their pipes!”

Coffee

Coffee was not just a staple on the trail, it was often the only thing left near the end of the journey.

“We still had coffee, and making a huge pot of this fragrant beverage, we gathered round the crackling camp fire — our last in the Cascade Mountains — and, sipping the nectar from rusty cups and eating salal berries gathered during the day, pitied folks who had no coffee.”

— Catherine “Kit” Scott, 1852

The coffee on the trail was transported as green (unroasted) beans, because roasted or ground coffee traveled poorly and rapidly lost its flavor. The beans were roasted in a skillet over a fire, then ground in the ubiquitous coffee grinder.

Other necessities

Palmer’s food list consisted of only the basics. Many pioneers brought additional items along to suit their own tastes, including such treats as dried meat, hard candies, chocolate, and various types of hard cheese. For those who brought the lactating family cow, butter was available, churned daily by the bouncing wagon. Nearly everyone brought lard for cooking, as well as tobacco in some form.

For medicinal purposes

Disease was the big killer on the trail. With so many people traveling along the same routes at the same time with far too little understanding of basic sanitation, this meant human waste, animal waste, and animal carcasses were often in close proximity to the available water supplies. As a result, cholera — a bacterial disease usually caused by ingesting feces-tainted water — was the greatest cause of death on the Oregon Trail. Typhoid (or as it was called, mountain fever), diphtheria, dysentery, malaria, food poisoning, and even scurvy were also diseases affecting the pioneers. And, of course, childbirth was made more dangerous simply as a result of the primitive conditions on the trail.

In the mid-19th century, effective medical supplies were limited. Marcy recommended a fairly sparse first-aid kit for the travelers containing “a little blue mass (a mercury-based nostrum recommended for varied complaints such as tuberculosis, constipation, toothache, parasitic infestations and childbirth pains), quinine, opium and some cathartic medicine (for constipation).”

Not included in Marcy’s list was one of the more popular medications of the day, often described as “medicinal spirits.” Fortunately this omission was remedied by his faithful readers, and there was hardly a wagon that didn’t carry at least one or more five-gallon drums of “medicinal spirits,” usually in the conveniently available form of whiskey, brandy, or rum.

“The brandy and whiskey we brought for medicinal purposes, but indulged in a little as we had just started on our journey. The first day, the cork came out of the whiskey bottle and spilled more than half to Mr. Tootle’s great disappointment. Indeed I don’t believe he has recovered from it yet.” — Ellen Tootle, 1862

Firearms

Every wagon carried firearms. While fears of frequent and deadly clashes with Native Americans were exaggerated in the popular press, the reality of such confrontations was considerably different. In his book The Plains Across, John Uruh estimated 362 emigrants and 426 Native Americans died because of conflict during migrations between 1840 and 1860.

Most of the travelers were equipped with muzzle-loading long guns, either muskets or (occasionally) rifles. Cartridge firearms did not become mainstream until the mid-1870s. Pistols were fairly rare, as they were expensive and not suited to the principle use of firearms on the trail (adding fresh meat to the dinner menu). Practically every wagon was equipped with gunpowder, shot molds, and lead for casting rifle balls.

“We stopped at Omaha several days for outfitting and the gathering of more emigrants as the Sioux Indians were on the warpath that summer and it was not safe for a few people to venture alone on the trip. Many emigrants arrived daily and when we were ready to start there were more than 100 wagons in our train and twice that many men, all armed, mostly with single shot, muzzle loading rifles. Some, however, had Henry rifles and Colt revolvers.” — Charles Oliver, 1864

Everything else

Several more articles could be written just on the clothing, camping supplies, day-to-day tools, and livestock supplies needed by the emigrants while traveling the trail. More could be said about those who brought cherished family heirlooms that had to be left discarded along the trail to lighten the wagon load for struggling oxen or mules. Farmers brought plow blades and precious seed. Skilled craftsmen making the trip often had to bring one or more additional wagons just to haul the tools of their trades, necessitating the hiring of drovers and adding more food to feed them. Emigrants brought books, Bibles, trail guides, and writing materials. Roughly one person in 200 kept a diary.

The end of the trail

With the exception of the very early years, travelers on the trail were rarely alone. Everyone jumped off from Independence at roughly the same time. Each delay caused by a swollen river or a slope failure across the road created a bottleneck that backed up the pioneers until the delay was overcome. Travelers grouped together while camping and moved together for protection. Items carried by one wagon would often be traded or sold to another. Hunting parties made up from several different families would scour the area around the trail for game to share at the evening meals. And romances, break-ups, and marriages were common.

A mishap, like getting off the trail and getting a wagon stuck in the mud, often meant waiting for help by the next wagon to come along. And help they did. No one was left behind, because anyone could become the next person in trouble. Everyone on the trail felt a kinship for their fellow travelers. They celebrated each other’s’ successes and consoled each other’s losses. No one was left behind.

Even upon arriving in Oregon or California, the travelers-turned-homesteaders were not left to fend for themselves. Many of the emigrants arrived starving, with no provisions left. Others had a bit of preserved food, but were sick and worn out from the journey. And many had spent their last dollar just making ends meet on the trail itself.

Those who had arrived earlier organized relief associations. These relief groups often sent regularly-scheduled pack trains back along the trail to help stragglers in need. This kind of assistance didn’t cease at the end of the trail. Most of the new settlers arrived in the late fall or early winter, far too late to put in a crop or do more than hastily construct winter quarters. But neighbors, churches, and civic committees worked together to keep the new arrivals alive, at least long enough for the settlers to get in a crop and “prove-up” their homesteads. Some referred to this as altruism at its best. Other (more pragmatic) folks considered that to have thousands of new neighbors both armed and starving was in no one’s best interest. Whatever the motive (and I can see no reason why both sentiments couldn’t coexist happily), those who were willing to work were given employment, even if the pay for their labors was in food rather than gold.

The immigrants became homesteaders, and the Western territories received the benefits of an influx of people who were willing to take the risks of seeking the unknown in hopes of a better future for themselves and their posterity.

I’ve been a modern backwoods homesteader for more than 25 years now. I’m here to report the community spirit is still alive and well amongst my neighbors and fellow modern-day pioneers.

I think it goes with the territory.

I’m just bettin Conrad still bares the scars of his arduous journey across the barren western landscape!!

Try being a puritan landing on the rocky eastern coastline with zero support systems and no less the burdens, more in fact, than the westward explorers. Just fact and truth. Now, turn your central air conditioning off!

My great grandmother’s family homesteaded to California. When I was a young boy we would go to their farm in Bloomington California. Grandpa had a spittoon in the living room. He had a still in the barn and grandma would not let him drink in the house. My grandma used to tell us that she did not ride in the wagon. She walked along side the wagon all the way. She was 4 years old when she made the voyage. She came to stay a few days at our house once in the 1950s. We watched a new tv show called Wagon Train and she had a fit. She said it was not like that at all. Oh I would love to spend some time with her today. What a tough and loving woman.

Thank you so very much for this article.

Enjoyed this article very infomative and well written..

This is great! My wife is an elementary school teacher and her class will be learning about the Oregon trail.

An enjoyable and informative read.

This is a wonderful article. It was very helpful compared to everything out on the internet now a days.

That was helpful?!

Very informational! ?

Love reading about the pioneers and their long hard journey across this country. Was always curious about the items they took with them. Only the toughest survived the trek. Amazing people….

Pretty common for folks to eat horses and mules too in them thar days.

I’ve read many articles and stories about heading west in the 1800s and it always fascinates me. I very much enjoyed this article, while none of it was new to me I found it very well written and engaging. Thank you!

This is a great article. Would love to see you expand it into multiple articles covering the rest of the items mentioned that pioneers took with them. I plan to read a few books on this too.

Really enjoyed this..very interesting I spent many springs and summers in the last frontier Alaska and to this day alot of people go there seeking a dream and a new start. Along the way you find cars vans R.V.a abanded Sad but true.

You have to be prepared have a trade or job waiting or a good nest egg.and so many things to prepare yourself for homesteading I’m hoping to learn and enjoy your magazine.I’m in Az now and trying to grow alot of my food have chickens and eggs.Getting old hasn’t stopped me yet. Never too old to learn more.

Very interesting and informative article. Thank you. I will see if my library has the book Conrad suggested.

People from East of the Mississippi have no clue as to what it means to head West with a dream and some stuff. The first thing you do is buy a couple guns and revel in the idea that you might really be free. East Coasters will NEVER understand that.

As for the rest, the book “A Pioneer’s Search For An Ideal Home” by Phoebe Judson reveals that journey to be one of danger, practicality, and faith.

Most East Coasters who make the trip usually go back home, proving that the experiences were wasted on them.

Really enjoyed this article.

Fantastic read,really enjoyed