By Jackie Clay-Atkinson

We’ve lived off the grid for decades. Throughout the years, we’ve traveled the path from living a very rustic lifestyle with few amenities to our current off-grid homestead with all the bells and whistles. But this didn’t happen overnight.

Montana homestead

Our path began on a very remote homestead in the mountains in west-central Montana. My husband, Bob, and I managed to pay cash for a 20-acre patented mining claim in the middle of the National Forest, five miles from the nearest neighbor. The property had a developed spring which had been piped down to a frost-free hydrant a few dozen feet from a small cabin. The cabin had one 8’x10′ bedroom, a tiny living room, and an 8’x9′ kitchen. The property had been fenced for horses, as the previous owners had planned on having a guiding service there.

There was no electricity, but there was a propane refrigerator, a gas kitchen range, and a gas light in the kitchen. These all ran off a 100-pound propane tank located outside.

The 20 acres was mixed between big pines, firs, and open meadowland for pasture. And the views were spectacular with the land being 1,000 feet above the Continental Divide.

We moved in with our 1½-year-old son, David, in early June, right after snow-melt in the high country. We brought a huge pantry’s worth of food along with some basic homesteading tools: a TroyBilt rototiller, 4,500-watt generator, gas barrels and cans, chainsaws, axes, lanterns, canners, ropes, chains, and a four-wheel-drive truck.

At first, we pitched a big wall tent we’d found free at the local dump (there was only one small hole in the side). We then hauled our horses up the steep, rocky switchback trail and freed them in the pasture. After cleaning out the stock trailer, we used it to bring all the food, supplies, equipment, and household goods up the hill. As we were in bear country, we left everything in the trailer, locked tight.

We cleaned out the cabin and began moving in. It was obvious we needed more room as there was absolutely no place to install our wood cookstove and no room for the big pantry we’d need when we were snowed in. From mid-December to late May, the road to our cabin would be impassable. Even though we had a ¾-ton Chevy truck with a snowplow on it, the snow would quickly stack up, with no place to push the snow after awhile. To prepare for the winter, we began buying and hauling hay for our horses in the spring.

After moving our supplies to the property, we got to work building a 12’x 20′ addition onto the cabin. As we were living on about $5,000 a year, we scavenged a whole lot of lumber from the dumpsters in the small town 12 miles away — enough to frame and side the addition. The rafters were poles, the roofing was scavenged lumber, but we managed to buy metal for the roof. (In wooded mountain country, the threat of fire is very real and a metal roof can save a cabin from burning to the ground.) The kitchen sink and two windows came from the dump. We didn’t add insulation since we couldn’t afford it. Luckily, the wood range we installed was able to heat the whole cabin except for the coldest days of the winter.

Next to the kitchen, we added a walk-in pantry with big shelves from floor to ceiling and a space near the entrance where I could store my wringer washer when it was not needed.

In our remote cabin in Montana, all our electricity came from a generator.

We ran it once a week to wash clothes, which two-year-old David loved to watch.

After building the pantry, we fixed up the remaining space for a bedroom for Bob and me, complete with a cast iron bathtub against the back wall.

As we were pretty broke, we knew we had to make every penny count. Those 100-pound propane tanks get fairly expensive to fill, and there was a chance we’d run out of propane during the winter when we’d be snowed in. Fortunately, the propane company in the nearest city had a four-wheel-drive delivery truck and agreed to deliver a 250-gallon propane tank before winter and fill it.

But even with the tank full, we knew we had to conserve or we’d run out before we could afford more. We also only ran the generator when absolutely necessary, usually once a week so I could wash clothes. While I was doing that, Bob and David would watch a VHS movie on the TV. It became our “fun day.”

During that time, our summer lighting needs were minimal due to the long days. As fall approached, we used kerosene and Coleman lamps as well as a few carefully-guarded candles. But as kerosene and Coleman fuel started going sky-high in price, we switched to the Coleman lantern that burned either Coleman fuel or gasoline. We bought a 55-gallon drum of gas on sale in the late fall and picked up a few cans of Coleman fuel as we could afford it. By only using the propane for the refrigerator, cooking on hot summer days, and the gas light a few nights a week, our 250 gallons of propane would last a year.

The 55 gallons of gas would last most of the winter for our generator, the one Coleman multi-fuel lantern, and occasional use in the snowmobile, which we used to access “civilization” in the winter. (We parked our Suburban at a friend’s house during the winter. Bob could snowmobile down to the Suburban, then drive the Suburban to the Post Office or local market.)

We had a small shed for the generator next to our outhouse in the backyard. For ease of use, we kept the walkway shoveled all winter long. If we had to go in the night, we used either an unlined pee pail or a poo pail with some wood shavings on the bottom (we kept another bucket of shavings nearby to toss a handful over any leavings). Toilet paper went in a bag nearby to burn in the wood stove later.

We carried water all winter from the frost-free hydrant in the yard. In warmer weather, we ran a hose into the cabin with a faucet shut-off on the end for convenience. At first, we took baths in a wash tub in the kitchen during the winter. Then after plumbing in a drain for the clawfoot tub, we used that for more comfort. To fill the bath, we heated water in two canning kettles on the wood range.

Our remote Montana cabin had a spring,

but our electricity came from a generator.

Minnesota homestead

Several years later, we moved to our new northern Minnesota homestead in February when it was -25° F. Our driveway was more than a mile long. There was no cabin, no buildings, no well, and no spring. But we did have a 26-foot-long travel trailer we’d outfitted with survival supplies and a 10×10-foot insulated ice fishing house we’d bought and refurbished for a living room.

We installed a wall-mounted propane heater in the living room. We had a propane fridge and kitchen range in the trailer, along with the generator we’d brought from Montana. We had no battery bank but did have a little more income, so we used the generator for lights during the night.

At first, we used a 100-pound propane tank to fuel the fridge and stove, but before winter was over, we switched to a 500-gallon tank.

We used the same “bathroom” as in our remote Montana cabin; two buckets, as there was no outhouse yet. Luckily we had a battery-operated shower which we could use in the trailer’s existing bathroom shower stall. I would heat a canning kettle of water on the kitchen stove then place it on the floor in the bathroom. After placing the battery-operated shower inlet hose in the canner and hooking up the outlet shower head, we had a nice warm shower. (We re-plumbed the shower drain into a pipe outside as any water going into the trailer’s gray water tank would freeze and crack the tank.)

We carried our water in five-gallon plastic cans from Idington Spring, seven miles away.

Shortly after we settled in, my elderly mom and dad came to live with us. Four adults in a travel trailer and fish house doesn’t work well when walkers are involved. So my oldest son, Bill, found us a free mobile home to use as a big cabin. (We were planning on building a stick-built cabin over summer but things got busy when Mom and Dad came.)

We still had no water but David, now 10, helped dig and build an outhouse down from the trailer. (I hate trailers, but sure loved the extra room and ease of helping Mom and Dad!)

Dad decided we needed a well, so he told me to hire a well driller to come out. After watching the driller go deeper and deeper, we got worried; they charge by the foot. After drilling down 300 feet through ledge rock, we finally got water.

We were still using the generator for power. We had no battery bank as there was no place to put one.

Suddenly, one night Bob was stricken with a bleed in his brain and the next night he died in the hospital, despite surgery.

Needless to say, it was a tough time for everyone.

But life must go on. Since Bob had died as a result of service-connected injuries during the Vietnam War (due to Agent Orange), David and I were eligible for survivors’ benefits. With this money, we managed to build a small log cabin shell erected on a basement. Losing a husband and father did not make the building as sweet as it would have been otherwise.

We finally moved into the cabin, now having the luxury of a well and septic system. Being off-grid, we couldn’t run the generator 24/7, so to have water available at all times, we installed two 300-gallon vertical poly water tanks in the basement. Then we installed a 12-volt in-line pump, powered by a deep-cycle battery, hooked to a small battery charger. That gave us the possibility of adding a propane water heater, which gave us pressurized hot and cold running water any time we wanted it.

Our carpenter friend, Tom, agreed to help us by finishing the cabin as I could afford it. This was often piece by piece, window by window. But slowly, we got the cabin finished.

We now had hot and cold running water, a wood kitchen range to help heat the house, and wiring through the house for “normal” power via our generator, housed in a shed 50 feet from the house. But it meant any time we wanted power, the generator had to be running. This was not cheap, especially when the gas prices were going up.

In 2006, we lost Dad. He was in his 90s and had a bad heart, but it was still hard.

About this time, I began writing to a homesteader guy in Washington named Will Atkinson. David and I continued working on our homestead and garden and I kept Will up-to-date on our progress.

Two and a half years later he flew out here to join us, and a year later, we were married. For a wedding present, Tom gave us a set of Harbor Freight solar panels totaling 75 watts. I had brought a 45-watt solar panel from Montana, and my son, Bill, had given us another.

Luckily, Will is very handy in many realms, including electricity. We bought four 6-volt golf car batteries and Will got busy and built a rack for the panels in the backyard. Up until this time we had not needed an inverter, as our house power was directly plugged into the generator, which generates a “normal” 120 volts AC. The batteries stored direct current power (DC), so we used an inverter to change the 12-volt battery power to household current. Pretty soon, we were charging the batteries in the basement with both those little solar panels and our generator. In the summer, we only had to run the generator to power the well pump, run power tools, and have extra power for the wringer washing machine, my desktop computer, or the television. At night, we could simply flip on a light switch and … there was light! To further conserve our electricity, I switched all of the light bulbs to CFLs. The difference was staggering! So was our reduction in the cost of gasoline to run the generator. But at inconvenient times, our batteries would run low and the inverter would beep as the lights went out. We got very good at finding a flashlight in the dark!

A little after this time, Will’s son, Don, in Alaska, found a used 450-watt wind generator next to the trash bin in front of someone’s house. He brought it home and sent it to us. Will bought new blades for it for about $100 and hooked it up to a telescoping pole, raised with a 12-volt winch off our ATV. But once up there, it wouldn’t turn. After quite a bit of investigation, Will found it just had a bad bearing. For less than $10, I found a bearing at a local shop. Will installed it, raised the wind generator on the pole, and let it charge. It’s been above our storage barn now for years, and still works well.

Our 450-watt wind generator was salvaged from the trash, but Will was able to get it mounted on our barn

and working without too much trouble!

A few years later, Will built a big rack for larger solar panels from a length of 4″ steel pipe and an old satellite dish bracket. He cemented the upright pipe into the ground. After saving for a long time, we purchased two discontinued 250-watt solar panels from a local manufacturing firm. We bought two more 275-watt panels from Home Depot, on sale of course. That gave us a little more than 1,000 watts. We also bought a new charge controller for the array as it was much larger than our old one. A charge controller basically keeps the batteries from overcharging on very sunny days, especially cold sunny days when the solar panels give off even more power than they do on warmer sunny days.

We bought six new 6-volt golf car batteries, a larger charge controller, and a bigger inverter. Will mounted the panels and wired everything, also hooking up a large battery charger with alligator clips to the battery so when we ran the generator it would also charge the batteries. We also switched our household lights from CFLs to LEDs, which gave us nicer lighting for less watts. The combined difference was impressive.

We still ran the generator to wash and dry clothes with our propane dryer in the winter, to run the well pump to fill our storage tanks, and to use the computer or television on cloudy days if we wanted to. But we had nearly unlimited use of lights and ran the generator much less.

We were thrilled to finally upgrade our Minnesota homestead with a well,

septic system, and this large set of solar panels and a bigger battery bank.

Just last year, we upgraded again, adding nine more solar panels

and more batteries. Now I can wash and dry clothes using solar power!

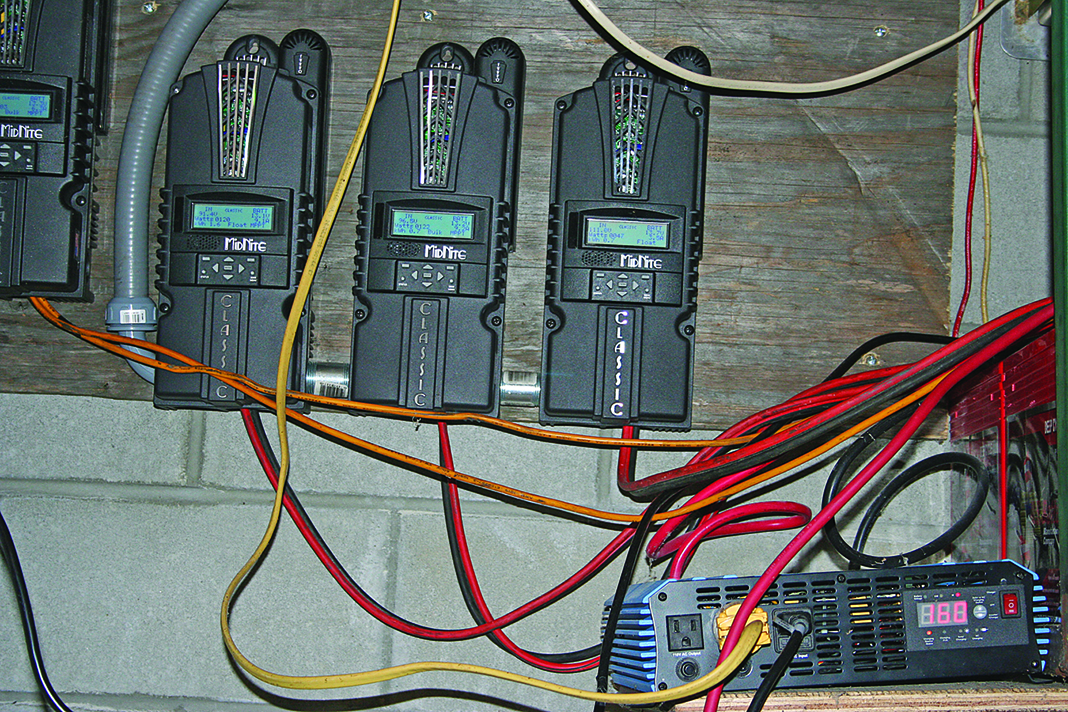

Last year, we were able to buy nine used 325-watt panels for a little more than $100 each. They had been part of a huge array that was never hooked up or used — then a big wind came up and tore the rack apart. The panels were undamaged but for very minor ripping of the holes in the aluminum mounting frames. So Will set about building a big mounting rack across the driveway from our house.

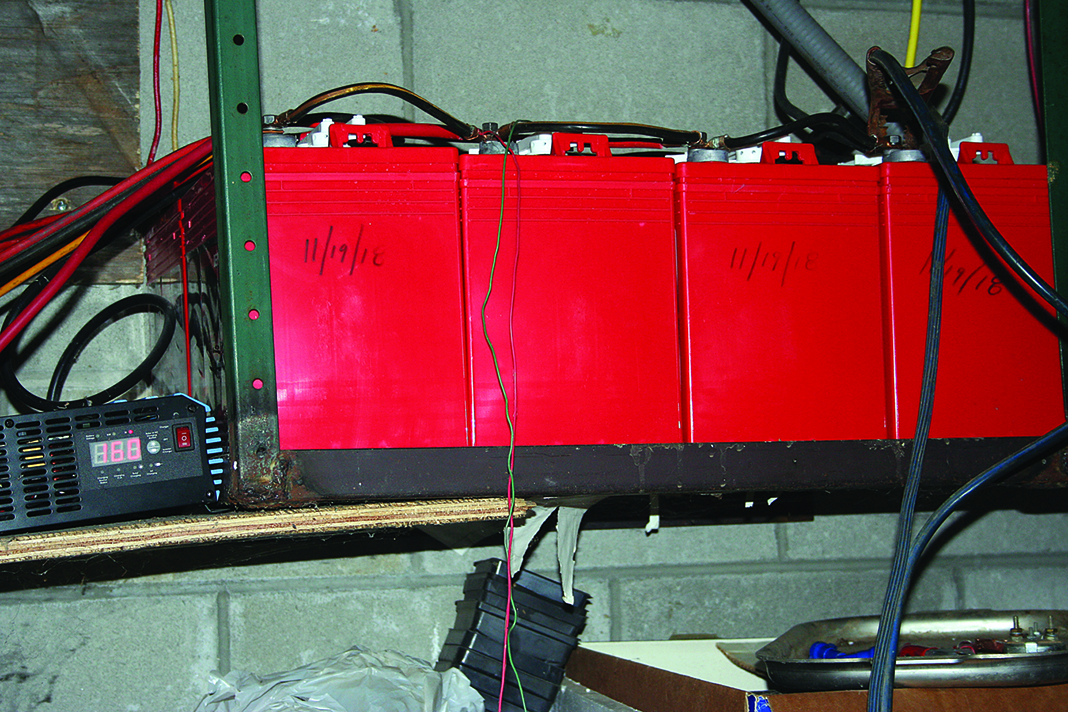

As the panels were more voltage, we had to buy a charge controller for each set of three. And as the chargers run nearly $500 each, we hooked up three first, then soon after, three more. By now our batteries were getting older so we also bought eight 6-volt golf car batteries. We were amazed at the extra electricity we were enjoying! My son, Bill, gifted us a used, propane double-door refrigerator with LED read-outs in the door. We also have a freezer for our home-raised beef in the basement. Our power use had increased, but the six new panels ensured our fridge never beeped “low power” and that the lights never went out at night after someone watched too much television.

When we added the charge controller for the last three panels, I found I could run the wringer washer and propane dryer solely with power from our solar panels and wind charger. We still use our generator to fill up our water storage tanks, but if and when the 220-volt pump finally dies, we plan on replacing it with a 110-volt pump. Then our alternative power can also draw our water.

With the first panels, we also added these batteries and a larger inverter

so we could power more appliances, such as our new freezer in the basement.

Adding the second bank of panels, we bought another set of new batteries as the old ones were getting tired after five years of being frequently drained of juice.

. With the second bank of large solar panels we also needed

one new charge controller for each three panels.

Tips & tricks

Even though we now have more than 4,000 watts of power, we have all our computers and the television on a surge protector strip with a snap on/off switch. These appliances can draw what are called “phantom loads;” they can use up power even when they are set to “off.” With the snap switch on the surge protector, off is truly off. Likewise, I try to use my biggest loads such as washing and drying clothes on bright, sunny days when we are generating lots of power.

We always turn off lights, just like my dad used to tell us as kids. Even LEDs draw power, so when we leave a room, we shut off the light. Like a tiny hole in your tire, you’re losing electricity by not conserving it. If we can use a hand mixer, we use it instead of an electric mixer. The less electricity we use, the more we’ll have for things that are truly important.

We still heat with wood and I cook mostly with wood, all harvested on our land from dead trees in the woods. We have a propane heater hooked up but have not used it since Mom passed away in 2010. We leave it hooked up just in case we have to be away for a day or two; turning it on ensures that the house won’t freeze.

Setting up an alternative power array doesn’t have to be costly. Just do it a little at a time (don’t combine old and new batteries together as it shortens the life of the new ones). Whenever Will would get puzzled, he’d call Backwoods Solar or Midnight Solar to get answers. And don’t forget the internet.

Take care when working with any sort of electricity, as the possibility of injury is very real. When in doubt, consult someone who knows what they’re doing. When Will was in the Marine Corps, he worked on big generators, which gave him an above-average knowledge of electricity.

It’s been a long journey to get to our place of relative power independence. All on a shoestring budget, too. But if we could do it, so can you!