|

|

| Issue #57 • May/June, 1999 |

For most homesteaders, the raising of livestock plays a crucial role in the home based economy. The types of livestock which you choose to include on your own place may be determined by your climate, the size of the homestead, food sources available, the available market (if you choose to sell some animals), and just your personal preference. It is sometimes argued that you can buy all of your meatbeef, chicken, pork, lamb, rabbit, etc.far cheaper than you can raise it. While this may be true when speaking in terms of money alone, other factors must be considered when referring to meat raised for homestead use.

These days, red meat in general, and beef in particular, is continually maligned as one of the greatest detriments to our health and well-being. I’m here to tell you that you can raise some mighty tasty and nutritious beef on your own place, and do so without a lot of the fat and chemicals which lace most commercially raised beef. Our own beef is raised mainly on grass and hay, with little grain or supplement. Free access to trace mineral and high-magnesium blocks, water, and pasture all help to turn out fine beef, much leaner than “store-bought” and at a competitive cost.

As one might expect, the first thing to consider when comparing home-raised versus store-bought meat is quality. Home-raised meat is born, raised, and processed with one thing in mind and that is to be used as food for the family. Generally speaking, commercially raised livestock is also raised with one thing in mind, that being to produce the most marketable product in the quickest time at the lowest cost and highest profit to the producer. Somewhere in there, quality has to suffer. Those of us who raise our own meat know what is going into it in the way of feed and additives. While many of us occasionally must fall back on an application of medication, etc. to restore or maintain the health of an animal, we know that no massive doses of hormones or steroids have been pumped into our future dinner entrees.

Another factor worth serious consideration is this. In the event of a serious emergencyeconomic or otherwisethe livestock raiser would have a valuable potential food source available. Obviously, we cannot place such reliance on our supermarkets or grocers. In hard times, grocery shelves and meat counters would likely be quickly depleted of their stock, leaving bewildered and dependent customers wondering what to do next.

If you have children in your family, the value and importance of having livestock on the homestead cannot be underestimated. Youngsters learn much by having animals around. The responsibility of having feeding to do, hay to help get in, manure to load into the spreader, and similar chores help a young person build self esteem and a good work ethic. A child can sense and build upon the feeling of contribution and importance in the family. He will learn that there are things which are expected of him and that his efforts are a valuable part of the family life. In doing this, we are helping to shape our youngsters into productive and responsible adults who are not afraid to work.

Children also learn the no-nonsense life-death cycle of animals which God put on earth for man to use wisely. A youngster growing up on a homestead which raises animals for food has no doubt about where his food comes from. Unlike many of his city-raised counterparts, he will develop a direct appreciation and respect for the life cycle of meat animals. Countless numbers of young people have learned the “facts of life” while observing animals on the farm and homestead. Many have even assisted parents in helping struggling animals in the miracle of birth. These youngsters, and their adults, develop a true respect for life and better understand the God-given miracles involved.

When getting into the cattle business, this may seem sort of obvious, but you should keep in mind the fact that cattle are BIG! An old beef cow can easily reach 1000-1200 pounds. Even the normally docile old animals can accidentally step on your foot, and if you get them excited or scared, they can seriously hurt or kill a person.

Our own experience with cattle has been interesting and educational, if not extremely profitable from a dollars and cents point of view. Cattle on most small places can do little more than keep the place from growing up in weeds and providing butchering beef for yourselves and for sale. Small landholders should not expect to get rich on cattle. This thought is echoed by our veterinarian, who has stated to me that he doesn’t see many small family herds of six or so cows with calves, make a real profit. But he adds, “A small herd like this will pay the property taxes and keep the pastures trimmed down.”

In fact, it is possible to sell a few fat calves, young steers, or butchering beef and make the program pay for itself and perhaps pay the property taxes as well. In addition, they can help keep your place from growing up around your ears. Over the years, we have had cows, bulls, calves and steers. Having raised bucket calves and having kept cows with calves, I have developed some educated opinions about the two methods of raising beef.

Cattle breeds

What type of cattle do you want? First, there are basically two general types of cattle: dairy and beef types. Among the common dairy breeds are Jersey, Guernsey, Brown Swiss, and Holstein. Popular beef breeds include Angus, Hereford, as well as the more exotic Limousine, Semintal, Charolais, Saler, and a whole pasture full of other breeds. Dual-purpose breeds such as Milking Shorthorns exist, but are not really common anymore.They do offer possibilities for the homesteader, however.

Both beef and dairy cattle have been carefully bred over time to do the best at what they were bred to do, whether it is produce milk or meat. The dairy breeds are biologically and physically made up to produce milk. That is to say, they are bred to convert feed to milk and do not have the heavily muscled body that the stocky beef breeds have. The beef breeds do best at converting feed into a meaty, heavily muscled carcass.

This is not to say that dairy calves cannot and should not be raised for beef. Countless ones have. Many a Jersey bull calf has been raised to become steaks and roasts. Often, however, when a homesteader breeds back the family milk cow to freshen, he chooses an Angus bull or other suitable smaller beef breed. This results in a renewed milk source and a good calf more suited to raising for meat since it will exhibit many of its Angus parent’s characteristics. Breeding the Jersey cow to a smaller framed type bull will help ensure that the smaller cow will have an easy birthing.

I have been around cattle for many years, but had not raised what we refer to as “bucket calves” or “bottle calves.” We started into this project by purchasing seven Holstein bottle calves from a local dairyman. In a dairy operation, the male calves are removed from the herd, whereas the heifer calves are kept and raised as milking herd replacements. At the time we bought ours, the going price in our area was about $125 each. It is interesting to note that this past season, some of the neighboring dairy farmers were getting no more than $30 a head. Some were actually giving them away after not getting bids for them at the local sale barn. They are usually sold as day-olds or at a few days old.

The folks we got ours from were very helpful and wanted to keep the calves for a full week to make sure they got off to a good start. They monitored them for scoursdiarrhea which can kill a new calf in a matter of 24 hours or so if not treated. The week also allowed the calves to receive some new milk from the mother cow. That colostrum, the first rich milk, is important to the calves as it contains many of the anti-bodies and bacteria needed by the new calf to get off to a good start. Those same anti-bodies and bacteria help to prevent the scours mentioned above.

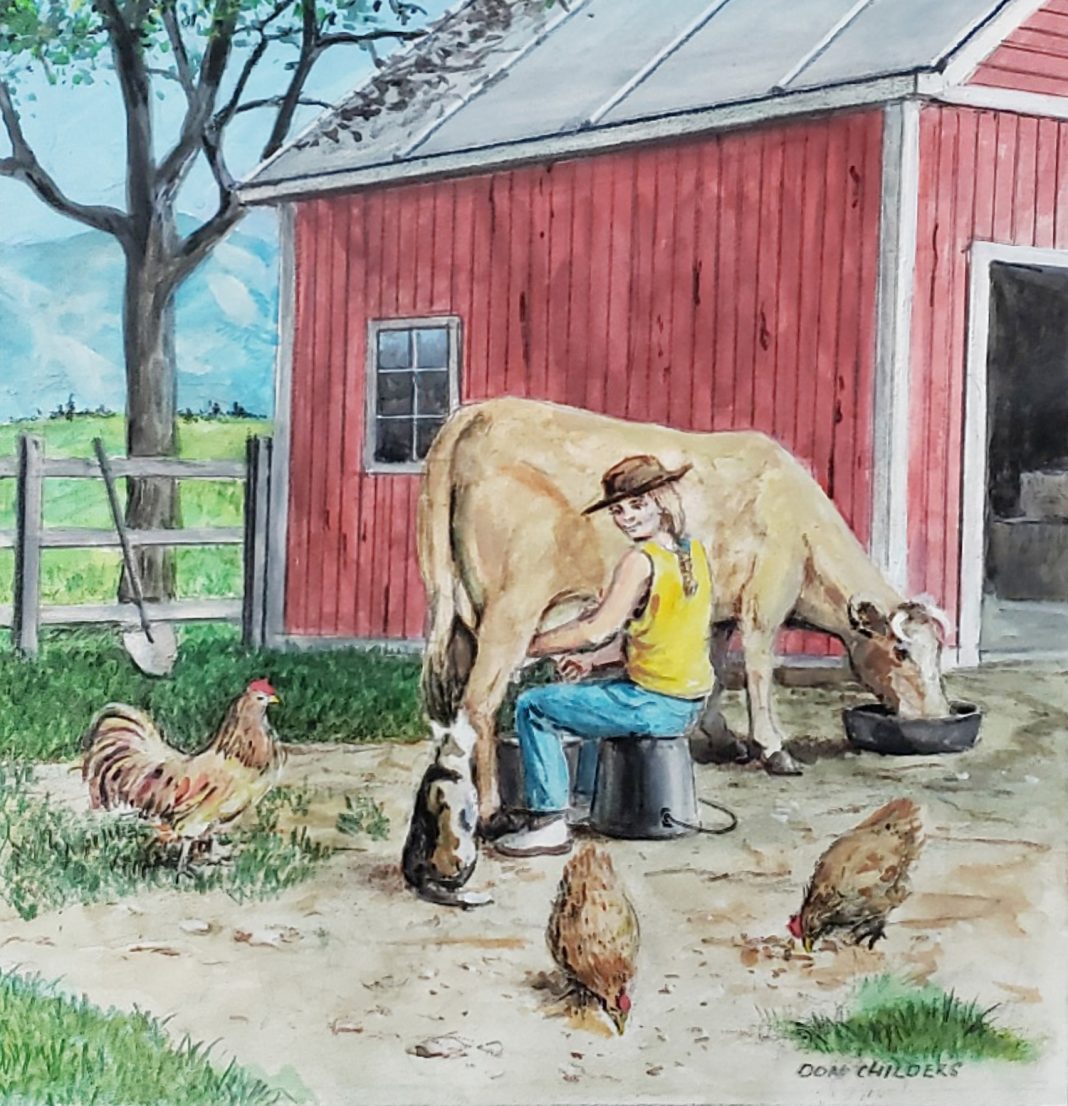

Our boys feed a Holstein bucket calf. The bucket is specially made for calf feeding and has a large rubber nipple attached.

Our bull calves were raised on bottles with calf starter formula, adding some dry feed at a few weeks of age, and weaned off the formula entirely at about 10-12 weeks. The calf starter is available at any livestock supply store. The dry feed was custom blended at the local mill. The formula is nothing magical, just a blend of 500 lb. of ground corn, 50 lb. of calf supplement, 25 lb. of molasses feed, and 2 lb. of salt. This is a good basic growing ration. Once the animals reach about five or six hundred pounds, we switch from calf supplement to steer supplement; otherwise the formula is the same. Make sure that weaned calves have clean water available at all times. A large steer or cow will need about 12 gallons of fresh water per day.

Medical problems were not serious during these early weeks. A couple of the calves had a bout with scours, but with some simple medications they came out of it all right. If a young calf does get scours, it is imperative to get them off the calf formula and get some fluid and electrolyte replacement into them. We did learn that in a pinch, powdered Gatorade can serve as good an electrolyte replacement as the stuff that comes from the vet. It is mixed with water and given just like the stuff from the vet. Your own vet can advise you on any potential problems which might be specific to your area.

We did not castrate the animals until they reached about 500 pounds. Our local veterinarian convinced us on this. He explained that the testes of the bull calves serve as natural hormone implants and cause the calf to grow faster during those first several months. Once they reached about 500 pounds, the vet was summoned and the calves were dehorned and castrated. This procedure is briefly painful, and the dehorning is somewhat bloody, but in a day or so, the event is seemingly forgotten and the animals are back to their routine. If you have purchased polled or hornless breeds of cattle, then obviously you will omit the dehorning procedure. Dehorning is not actually necessary, but it does help to prevent accidental injuries to the other cattle or to humans. The dehorned animals sell a little better on the market, as well. As for converting bull calves into steers, I recommend “cutting” as the best method. Other methods such as banding and clamping are effective if done properly, but this one is sure-fire. I also consider it healthier for the animal.

Since Holstein cattle are bred to produce milk and not beef, they seem to spend the first year just developing their frame. Not until the second season do they seem to start to bulk up much. Even then, Holsteins don’t put on the muscle that the beef breeds do. They eventually do fill out well, however. On the other hand, Holstein beef is a rival to any in taste and texture. These big cattle do indeed produce some very tasty steaks, roasts, and burger.

As interesting and educational as raising the bucket calves was, I really prefer to just let the old cow raise the calf. Therefore, we currently have only beef-breed cows and calves on our place. These are good Angus-Hereford cross cows bred to an Angus-Saler bull. Some may ask about birthing or birthing problems. We have had dozens of calves born on our place, and I can think of only one loss. Just a few weeks ago, I was cutting firewood in a woodlot above one of our pastures and watched one of the old cows give birth. I have helped with a birthing or two, but even then, I don’t think I was really needed. As this is written, we have four new calves and should be getting a couple more any day. Problems are normally few with an arrangement like this, for in most cases, the cow is much better at raising the calf than a person is.

Hay

You will need to provide a source of hay for your animals. In most areas, most of us are able to allow the animals to graze during the summer months. In winter, however, hay must be provided. Here is a basic question: What is hay? Hay is simply grass that has been cut and cured for later use as food for animals. It is stored loose, in small square bales or in large round bales. Hay prices vary widely across the country. Around here, it is usually sold by the bale. In the west, hay is normally sold by the ton. Small square bales weighing about 50-75 pounds will normally run from $1.00 to $1.50 for mixed grass hay. Alfalfa can run up to $3.00-5.00 per bale. Large bales come in many different sizes according to the make and size of baler turning them out. The farmer can usually let you know the equivalent in square bales and base the price accordingly. As for loose hay, I can tell you that it is simply a lot of work. I don’t know of anyone putting up loose hay other than the neighboring Amish farmers. Even many of them are switching to ground driven square balers pulled by their teams of husky horses.

Some time ago, I heard this question: Is hay the same as straw? No. Hay is an irreplaceable food source for our grazing animals, especially in winter. Straw is a by-product of the grain harvesting process. It is the stem and leaves of a grain stalk that is left behind after the seeds have been removed from the seed head by the harvesting equipment. Straw has no nutritive value; however, it is valuable as a bedding material. Wheat straw is the most common type of straw, but any of the cereal grains such as oats, barley, rye, etc. can yield good straw after harvesting.

A mature cow will need roughly a third to one-half a bale of hay per day during the winter or if on a site where pasture is not available. As I mentioned, we feed hay only during the winter, along with a bit of mixed grain feed.

Fencing

Good fences are necessary to keep cattle in. A cow or steer grazing indiscriminately through the neighborhood may or may not incur the wrath of the neighbors. But why take the chance? Chances are it wouldn’t make you or the cattle too popular.

If using standard fencing, I recommend sturdy woven wire on stout posts. Woven wire comes in different heights, but I’d recommend the 39-inch. When putting up the woven fencing, allow a couple of inches extra at the bottom and top. After it is erected, stretch and add a strand of barbed wire on the bottom and the top along the entire length. Cattle will really stretch to get to tasty plants outside their fenced area. These strands of barbed wire will convince them not to stretch under or over the top of the woven wire and will save you much in the way of maintenance and repair.

Some sections of our fence is barbed wire only. I prefer to use four strands of barbed wire, but three will suffice in a pinch. If you can, use four. It just makes a tighter fence.

Electric fence will work in most cases. It also offers the option of being easily moveable to fresh pastures. Once the cattle are trained to recognize its ability to cause discomfort, you should have no problem. The so-called training is nothing more than simply allowing them to bump or brush the fence while grazing. We used a single strand of electrified barbed wire on one pasture, and it kept in four large steers without a single problem or escape.

Pasture

On good pasture, a couple of acres will maintain one animal. Naturally, in drier climes, more acreage per head is needed. Plant varieties for pasture vary from region to region. Local farmers and ranchers, as well as your local Agricultural Extension Service, can recommend types for your area. It is best if you can rotate the animals out of one pasture and into another from time to time. This practice allows the pasture to rejuvenate its plant growth and allows any parasites to die off.

Shelter

Cattle need a draft-free yet not air tight shelter. I used to think that was a contradiction. However, realize that a good shed with three sides closed in and the open side facing out of the prevailing wind makes a good shelter. Do not make the shelter airtight. Cattle give off a lot of moisture, and if it cannot escape all kinds of health problems in your animals will result.

Shelter for your animals doesn’t have to be anything fancy but it does need to be sturdy. These big animals stomping around can knock a lot of things loose if not secure.

Marketing your beef

Our Holsteins were kept for two full growing seasons. Five of the steers were trucked to the Louisville livestock market where they brought a pretty fair price. The other two were kept for later sale to friends. We were paid at the market price on the day they were taken to slaughter. We could have easily advertised and gotten a higher price, but we were selling to friends, so the market price suited us.

This holder was made from scrap wood and hardware. Feeding four hungry calves at one time can get pretty lively. Hang on!

Right now, we have beef-breed cattle running on our placesome Angus-Hereford crosses. They pretty well take care of themselves during the summer months and require just the normal feeding and watering during the winter. The Angus bloodlines mean smaller calves and easier births. Crossing the two types of cattle gives a good, vigorous animal with a solid, desirable shape and meaty carcass.

Another real possibility for the small farmer/homesteader is to sell to a select market. By raising your beef organically, that is with clean natural feeds and no additives or hormones, you will be ending up with a premium product which can command a high price if marketed properly. If, for example, you live near a medium to large urban center, people will be happy to pay more for your lean, farm raised beef. A small, inexpensive advertisement in the local newspaper or at a nearby health food store or co-op will usually result in all the customers you want. This will require diligence on the part of the raiser to assure that his stock receives the natural, additive-free feed which produces the higher priced beef.

Maybe you want to market locally. Even farmers and other country folks do not raise much of their own food these days. Advertise in the local paper and you will be surprised at the folks who are interested in buying good beef. If you have your own beef processed at a local meat processor, then you can offer to haul your customer’s animal at the same time as an added sales pull. You will be able to get at least the going market price and usually a bit higher. You will be able to ask around at the local meat processor, farmers, and others who have a good idea what you can get for beef. If you can guarantee that your beef is “additive-free” or “organically raised,” then you can get a better price yet. Just the fact that your beef is raised on a small homestead and not in a “beef factory” feedlot means a lot in the way of producing clean, low- or non-medicated, additive-free beef. Our own beef is fed only grass and hay, with a smattering of grain during the winter months. We never confine our beef animal prior to slaughter for the purpose of “pouring the grain into it.” In my experience, this does produce heavier cattle sooner, although I’m not sure the profit outweighs the cost of the extra grain. It also produces beef with a lot more fat on it throughout the meat. This “marbling,” while desirable for “gourmet” cuts, is not really healthful. Our grass-fattened beef does us nicely, thank you.

So, if you are interested in picking up a calf or two to raise for your own use and possibly to sell to family or friends, then raising bottle calves may be the thing. Perhaps you would rather buy a mature bred cow or a cow and calf. Consider your alternatives and your resources to help decide the operation which is best suited for you. Whether you raise just one animal for your own consumption, or half a dozen to sell, you will be amply rewarded for your efforts.

For more information, look for these books. Some of them may be out of print, but patient and diligent searching have helped me add them to my shelf.

- The Family Cow, by Dirk van Loon, Garden Way Publishing;

- Raising a Calf for Beef, by Phyllis Hobson, Garden Way Publishing;

- A Veterinary Guide for Animal Owners, by D.C. Spaulding, D.V.M., Rodale Press;

- The Stockman’s Handbook, by M. E. Ensminger, Interstate Publishers;

- The Cow Economy, by Merril and Joann Grohman, Coburn Farm Press.