By Dorothy Ainsworth |

|

| Issue #86 • March/April, 2004 |

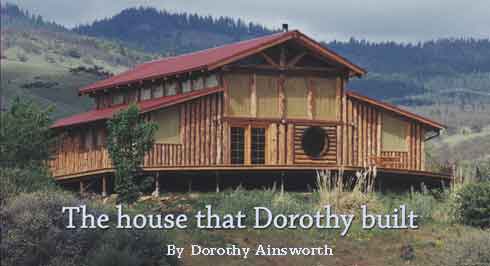

This isn’t the first time we’ve had an article by and about Dorothy Ainsworth. Throughout the text are editor’s notes refering you to the others. I think the lesson of the big, beautiful log home that Dorothy built is one of determination. She had very little money, but lots of guts. Dave Duffy

I wanted out. Out of the big city, out of the smoky restaurant where I worked as a waitress, and out of the cubbyhole where I lived with my two kids. There just had to be a better lifestyle, I pondered, even for a single mom on the ragged edge of survival.

|

I dreamed of a country homea rustic house in “the hills far away” where I could pretend to sing like Julie Andrews and the chipmunks wouldn’t know the difference.

Divorced and free from the shackles of convention, my desire for long-range security and self-sufficiency flamed into passion. At 37 I asked myself, “If not now, when? If not me, who?” So, down to the lint in my pocket and with the North Star as a windbreak, I started out on the long road to freedom.

I scouted out the best culturally rich small town I could find (Ashland, Oregon), secured a waitress job in advance, and sold our belongings at a garage sale. We loaded up the old Pinto station wagon that sported its bumper sticker saying: “Go around. I’m pedaling as fast as I can.” And we were off. With son’s piano and daughter’s horse in tow, happiness was Reno, Nevada, in my rear view mirror.

It took me a year to find an affordable piece of land, secure a loan, and come up with a practical plan to build my dream house on a frayed shoestring (tips). With a 40-year USDA FmHA loan, I bought 10 acres for $40,000 at 6.5% interest. The property had two old outbuildings on it that I remodeled into storage and temporary living structures, while I researched my options.

To my delight I discovered that all over the U.S. where there is forested United States Forest Service (USFS) or Bureau of Land Management (BLM) land, one can get a “pole permit” to obtain enough logs to build one’s own sheltercheap (3¢ per linear foot, here).

|

After studying almost every how-to construction and timber frame book at the library, I drew up some plans, bought an old pickup and a chainsaw, and my two teenagers and I gathered enough logs to build a small all-purpose structure. One hundred and eighty lodgepole pine logs cost me $42.00.

My first log construction

I chose vertical-log construction because short logs (8 inches by 8 feet) were manageable and fit in the pickup. There was minimal notching and they didn’t shrink in length. I lined ’em up, spiked ’em in, and had a wall. The labor was intense, but being a workaholic with the mindset of a carpenter ant, I developed a high pain threshold in a hurry.

Having been reared in a large family by lively eccentric parents, I was taught early to either rely on my own resources to create what I wanted or have nothing at all. Poverty was dignified by laughter, but the work ethic was law. (See BHM issue #32, March/April 1995 or A Backwoods Home Anthology: The Sixth Year.)

At age 11, I ironed for 50¢ an hour on Saturdays and mowed lawns for neighbors so I could buy fabric three yards for a dollar. I made all my own clothes on a treadle sewing machine and felt warm with pride as I twirled around in each new outfit while mom beamed and lavished praise.

|

Little did I know I was developing an ability to look at raw materials and flat patterns and instantly visualize the three-dimensional finished products. I would someday do the same with lumber and blueprints.

That day came at 40-years-old as I stood staring at my huge pile of logs. Goals were dreams with a deadline so I grabbed my drawknife and started peeling.

Eric and Cynthia, now 19 and 20, had gone off to pursue their interests in the arts (classical music and photography), so I was on my own. For the next three years of weekends, I toiled alone in a self-imposed apprenticeship program of trial and error by practicing on the “piano studio,” as I came to call it. (See BHM issue #27, May/June 1994 or A Backwoods Home Anthology: The Fifth Year.) I finished it up for a grand total of $15,000 (1000 sq.ft.). The pay-as-you-go method stretched my budget but didn’t break it.

Building the main house

With newly found confidence, I felt ready to tackle the main house. I knew exactly what I wanted but was limited by the harsh arithmetic of a $12,000 a year income, a rudimentary level of craftsmanship, and mostly hand tools.

|

The design would be spacious and well-lit and functional with simplicity and naturalness prevailing. I drew plans for a lofty gabled barn-style house with shed wings, and made a model to go by. For strength and beauty I decided to use timber frame joinery (pegged mortise and tenon joints) applied to logs. I put in a foundation of huge pilings and large girders to support the weight.

As serendipity would have it, I met a Bunyanesque hunk at the local fitness center and he volunteered to help me get the logs I needed. Never mind he was half my age; we fell in love and time stood still. Every “date” in the summer of ’89 was a romantic rendezvous into the woods, where togetherness meant one of us on each end of a log. We “bonded” like construction adhesive.

After stockpiling 300 logs, Kirt continued with college and I worked on the house as my personal quest. Over the next six years, I put in 6,000 hours labor, asking for his help only with extremely heavy tasks.

The log-dominated “timberframe” consisted of four bents (two uprights and a horizontal) creating three bays (space between bents), joined together by connecting girts, and reinforced with 45° knee braces at the intersections.

|

I laid out the big log “H”s on the deck and proceeded to cut the mortises (slots) and tenons (tabs) with a small electric chain saw, auger bit, and chisel. Kirt helped me erect the bents, secure them at the base with pole barn spikes, and install the connecting girts. We stabilized the frame with 10 pairs of 4 x 10 rafters on four-foot centers. I roofed with red metal.

With the basic skeleton complete, I welcomed the challenge to flesh it out on my own. I methodically put up the walls, one log at a time, toenailing three 12-inch spikes into predrilled holes in the base of each log. To save my wrists for waitressing, I gripped the hammer with both hands and wailed away with 40 whacks on each nail, driving them down through the sub floor and into the foundation beams underneath. I swapped the log ends alternately to even out taper and keep the walls plumb, and set each log two inches over the edge to shed rain.

Next came the 36 windows and 9 doors to button the place up. I made all the doors out of T&G pine and window frames from Douglas fir 2x4s.

The inner walls remained rustic (visible logs), but the outer walls had to be insulated and sheetrocked on the inside and chinked between the logs on the outside.

|

I hired an electrician to do the wiring but painstakingly did the plumbing myself and miraculously passed the inspection.

The main house burns

Racing toward the finish line, I rented scaffolding to facilitate caulking and sealing and staining the entire outside of the house. Night and day, up and down the rungs I climbed, buttering the logs with my linseed oil concoction until they glowed like the sunset. I wiped the baseboards with a tiny cotton T-shirt and laid it out to dry. On June 29, 1995, the rag spontaneously combusted and burned the house to the ground while Kirt and I were both at work. We put the fire out with tears. We were back to “log one.” (See BHM issue #38, March/April 1996.)

I had nominal insurance to cover tools and a new foundation, but rebuilding would have to be done the hard way all over again. Fortunately though, being a waitress in a coffee shop meant I knew a multitude of townspeople. They rallied together and threw a wonderful music benefit in my behalf and raised enough money to buy foundation beams, floor joists, and rafters. Then Kirt and I trudged back into the forest with our trusty chainsaw and old Ford pickup. If this rough-hewn man in Levis and flannel shirt wasn’t the marryin’ man, he was certainly the carryin’ man.

Starting over

|

After we stockpiled and peeled 300 logs, Kirt took a leave of absence from his job to help me rebuild the basic structure in only two years. I continued to waitress and do the finish work by making doors, cutting and fitting knee-braces, creating a “tree” as a king-post, and building the stairway and railings and decks over an additional three-year period. (See BHM issue #50, March/April 1998, or A Backwoods Home Anthology: The Ninth Year.)

I documented the project with photos and videos and kept track of every cent spent on materials. House #2 cost about the same as House #1: $15/sq.ft., for a total of $30,000.

Five years after the fire I finally had my house back, and artistically speaking, I liked it even better than the first. This time around we were able to find curved logs for the braces, stair rails, and king-post “tree.”

Lodgepole pine usually grows straight and narrow, but two lone trees drowning on the edge of a wet and soggy meadow were “beautifully deformed.” We took all those dramatically arched and gnarled branches and ended up using them as the most prominent supports and handsome finishing touches in the house.

|

That’s the charm of building a log home. There is an inherent beauty and uniqueness in every log. You simply relocate and rearrange Mother Nature’s handiwork. Natural elements, with all their flaws and character traits, transform even a modest shelter into a stunning work of art.

You don’t need a degree in architecture to design your log home. Do some soul searching, use your imagination, and make a list of everything you’ve always wanted in a home. Then sit down at the drawing board and incorporate those features into a floor plan and exterior design you like. Build a scale model out of balsa wood and 1/4-inch dowels (logs) to “test drive” your layout. From your model you can determine how many and what size logs you need.

The vertical-log method of building is extremely versatile. The logs stand on their own, have incredible strength, and don’t shrink in length. Put up a wall anywhere you want as long as you have a sturdy foundation under it. Create archways and round windows, a curved wall, orwhat the heckan entire round house. Stand the logs up and spike them in; the possibilities are endless.

There are books galore to help you calculate foundation loads and roof requirements. Draw up your plans and submit them to the local building department. The experts there will work with you if changes or corrections are necessary. Chances are they’ll tell you, like they told me: “It’s overbuilt,” and that’s it. As soon as your plans are approved, you can get on to your next step, which is the gut busting work of gathering and stockpiling your logs. Now is the time to muster up some real pioneer spirit.

|

I celebrate a certain degree of poverty; it’s the mother of ambition. Because I had a lot more drive and energy than money, I had to resort to the self-serve, cut’n carry mode of logging. Although it wasn’t easy, it turned out to be one of the most satisfying and rewarding experiences in my lifethrice. I highly recommend it.

Tromping around in the forest is more than a breath of fresh air. It’s an awakening of all the primeval senses and a startling appreciation of the huge and the awesome. Then, to top it all off, you get to run around with your USFS permit in one hand and a chainsaw in the other while selecting the trees that will actually become your home. The dialogue can get downright emotional: “Ooo, there’s a beauty.” “Hey, I want that one right in the middle of the living room!” “Let’s cut it here to preserve this chipmunk hole.” “Look at this big protruding knot…you could hang your coat on it.”

There’s no substitute for the exhilaration and exhaustion you feel after hours of extreme labor and artistic choices, except maybe winning a marathon. As you drive the old pickup home with another load of perfectly imperfect logs, you know you’ve just spent a day actually living your dream. You can’t rush the process because you’re only human, but with each trip in and out of the woods, you are a little closer to your goal, and that is profoundly satisfying.

Kirt and I tried our best to be compassionate, environmentally responsible tree surgeons and thinned out only the trees in grossly overpopulated areas. We had a 600-acre “shopping mall” of timber to choose 300 short logs from, and did so judiciously. Several logs came from storm-damaged and root-sprung trees, and many tall trees provided four or five logs each. I even “hugged” a few logs real tight, but only to facilitate carrying them as I waddled along, grunting and panting to the truck.

After you have all the logs you need, the next aerobically enjoyable and artistically satisfying step is peeling them. It’s Zen-like. You and your drawknife become oneslicing off the bark in rhythmic strokes, creating a hand-carved design of dark and light swaths. You can alternately cut long and short, deep and shallow, and straight and squiggly to achieve any pattern you like. It’s easy and it’s fun. The only problem is, it’s addictive. Even after you stop for the day, you continue to feel the urge to champher the edges off of everything. I’ve peeled 780 logs for three structures and the drawknife remains my favorite tool.

|

While each log was still on the peeling stand I splashed it with a concoction of linseed oil, turpentine, and maple-colored stain, because I couldn’t wait to see the knots and grain and swirls and whorls come alive in technicolor. That visual inspiration kept me going and the stain protected the logs from fading in the sun.

With the preparation stage over, you now have a massive stockpile of well-groomed logsall “spruced up” with a haircut, shave, and a tanready to stand proudly at attention in their permanent places to protect you from the elements.

The rest of the story is just carpentry: hammering, sawing, drilling, gluing, and screwing. Every little accomplishment is its own reward, in a long and arduous process. By the time your house begins to take shape, so will you. Your building skills and physical prowess will grow right along with your confidence and self-esteem. Don’t be surprised to discover that the journey itself is so fulfilling that moving into the finished house is almost anti-climactic. (For more detailed building instructions, see BHM issue #50, March/April 1998, or A Backwoods Home Anthology: The Ninth Year.)

After you celebrate the completion of your masterpiece, you can wallow in the luxury of decorating it. This is the fun part. There’s an old saying I adhere to: “Never have anything in your home that you don’t believe to be useful or beautiful.” Stick to that, be true to yourself, and you can’t go wrong.

Decorating my new home

|

But you might ask: “What goes with logs?” I would answer: “Almost everything!” My rule is “no rule.” A combination of rustic motifs can go together with logs and each other. Wood goes with leather, metal, stone, mirrors, and plants, just to name a few compatibilities.

Personally I am fond of wood, iron, copper, brass, and terra cotta pottery. Anything nautical is beautiful to me: portholes, brass lanterns, masts and nets, and wainscoting. If I hadn’t built a log house, I would have built a wooden boat with a big cozy cabin and a galley. In fact, I once entertained the idea of building a huge ark if I was unable to get a building permit for a house. To foil the inspectors, I would pretend to be a religious zealot preparing for the next flood. Alas, it was just a fantasy. But I did fashion a “widow’s watch” at the top of my stair landing. And along that same theme, I built two large round windows for visual appeal and lined the deep frames with narrow T&G fir and brass nails.

I also like the western influence: saddles and ropes and leather and hats, and I have my daughter’s saddle and chaps on display in my living room. The horse tack fits right in, as does my son’s nine-foot grand piano. The log interior compliments both.

My stair banister, kitchen-pot hangers, and closet rods are all black iron-pipe attached with black flanges and brass screws. The house wiring is visible in black electrical-conduit, for an industrial look. The front door has a black iron porthole with brass wingnuts. And, as I said, all the doors are T&G pine with massive black hinges and wrought iron hardware.

I used huge laminated beams (glu-lams) recycled free from an old store ceiling for my counter tops and dining room table. I built a solid butcher block out of hard rock maple for my kitchen. It’s three-feet square and a foot thick. Needless to say, it stays put.

|

There’s a river-rock shower in the loft bathroom. I painted the stones warm earthy tones to go with the rest of the décor. (See BHM issue #77, September/October 2002.)

Some of my exterior log walls had to be sheetrocked on the inside for insulation purposes (code requirement), but it turned out to be a good thing. The delicately-textured white walls contrast nicely with the rough amber-colored log walls, and provide a flat surface for hanging shelves, mirrors, and artwork. A mix of rusticity and refinement, like leather and lace, is pleasing to the eye.

For all my windows I sewed cotton-duck drapes and curtains, installed brass grommets and black shower-curtain rings to hang them with and used black-electrical conduit for the rods. (Fabric was $3/yd., rings 12/$1, conduit 10¢/ft.) On hot summer days diffused light filters beautifully through the curtains and is sufficient for all my plants to flourish.

For the beds I made diamond-patterned Levi quilts from recycled jeans. (See BHM issue #77) I built a log crib, early pioneer style, for my grandson Zane, (See BHM issue #69, May/June 2001.)and made him his own little Levi quilt to match the others.

Just as low-budget decorating is a necessity, low-maintenance housekeeping is a must and dictates most of my decorating decisions. I chose low-nap heavy-traffic carpet so dogs and cats and kids can run wild through the house and nobody cares. A house is to live in and live it up in. Rustic materials weather well and don’t show the dust. Nicks and spills are camouflaged in textures and colors that grow richer and richer with age.

Being a minimalist, I resist accumulating “stuff” that requires a lot of time and energy to take care of. For me, life is too short to starch and iron doilies, no matter how pretty they are. I’m a wash and wear kinda gal.

Learn more about Dorothy and/or contact her at her website www.dorothyainsworth.com