By Jim Capossela

During open water season, the dedicated fisherman dreams of a trophy gamefish to hang in the fishing camp, or, increasingly, to photograph and return to the water. During those three seasons, relatively few anglers target panfish. But in winter, that’s exactly what we’re after. We’re not averse to a nice bass, walleye, or trout now and then, but those mild, white-fleshed panfish draw most of our devotion. These fish are prolific and generally abundant, and while you can probably overfish any species, I’ll stick my neck out and say that it’s pretty unlikely you’ll overfish the little guys. I’m speaking here of species in the sunfish family, especially bluegills, plus white perch, yellow perch, and crappies (there are a few others in other regions of the country). Even if you mainly practice catch and release, I think there’s a strong ethical basis for taking home a few panfish for the dinner table now and then; we never take more than we need and never waste a fish.

Rather than try to cover the whole big wide world of ice fishing — methods and approaches vary so markedly from region to region and even lake to lake — I thought I would focus on just four areas and within each provide some of my best tips and insights. Beginners will find some solid advice here, and old hands might pick up a tip or two. I’ll follow that with a few recipes for these delicious wintertime fish.

Bluegills are one of the main components of the ice fishing catch in many regions, but you need to fish for them with specific techniques and in specific places.

Ice safety

I’ve spent not hundreds but thousands of hours on the ice, and I’ve only fallen through twice. But that’s not what scared me.

We were aiming for a lake in a rugged mountainous area less than an hour from my home. In winter, any road near it is closed due to snow, so we had to haul our gear in on sleds. With the difficult access, I thought the fishing might be pretty good. But all we caught was small pickerel. By late morning we’d had enough and decided to try another lake in the same park, one closer to the road but about which we knew even less.

The ice was semi opaque from recent weather systems and covered with a dusting of snow, making it hard to judge ice thickness at a quick glance. But that first lake, just a few miles away, had had a foot of ice; surely this lake must also be very safe. We walked right out without testing with our spud bars. Near the midpoint of the lake my cousin spotted a fissure, which should not have been there. He poked the adjacent ice and his bar went right through. Much of the lake had only two to three inches of ice, less adjacent to the fissure, and overall the ice was very uneven, possibly due to springs. If we had charged out a little more intrepidly and not spotted that fissure, it might have turned out to be a very bad day. Admittedly, it was not a deep lake. But as I wrote somewhere once before, it can take just six feet of water and an old bluegill pond to put you on the other side of the Ouija board.

We beat a retreat to another nearby lake and never forgot that seminal lesson: never become overconfident or complacent on the ice. Or, as I think it might say somewhere in the Bible, “Pride goeth before a fall.”

Fish taste better in wintertime.

And for those times that I fell through? In late season, as the land heats from the ever higher sun, the land transfers that heat to the ice, and the shore ice starts to go first, as every experienced ice fisherman knows. Those two times (or more) that I broke through the ice were in very shallow water and there were no consequences other than a good wetting up to the knee. It was impatient and dumb but not unsafe. There were better places to get onto the lake if I’d only taken a few more moments to look.

Ice safety is too big a subject to cover in a short article, and it’s one of those places where a little bit of knowledge can be a dangerous thing. There are no doubt effective tutorials on the subject of ice safety on the Internet, and it is to those sources that I refer you. If you are a beginner, definitely try to go out with experienced ice anglers, and don’t go out on a lake where there is no one else fishing.

Cutting the ice

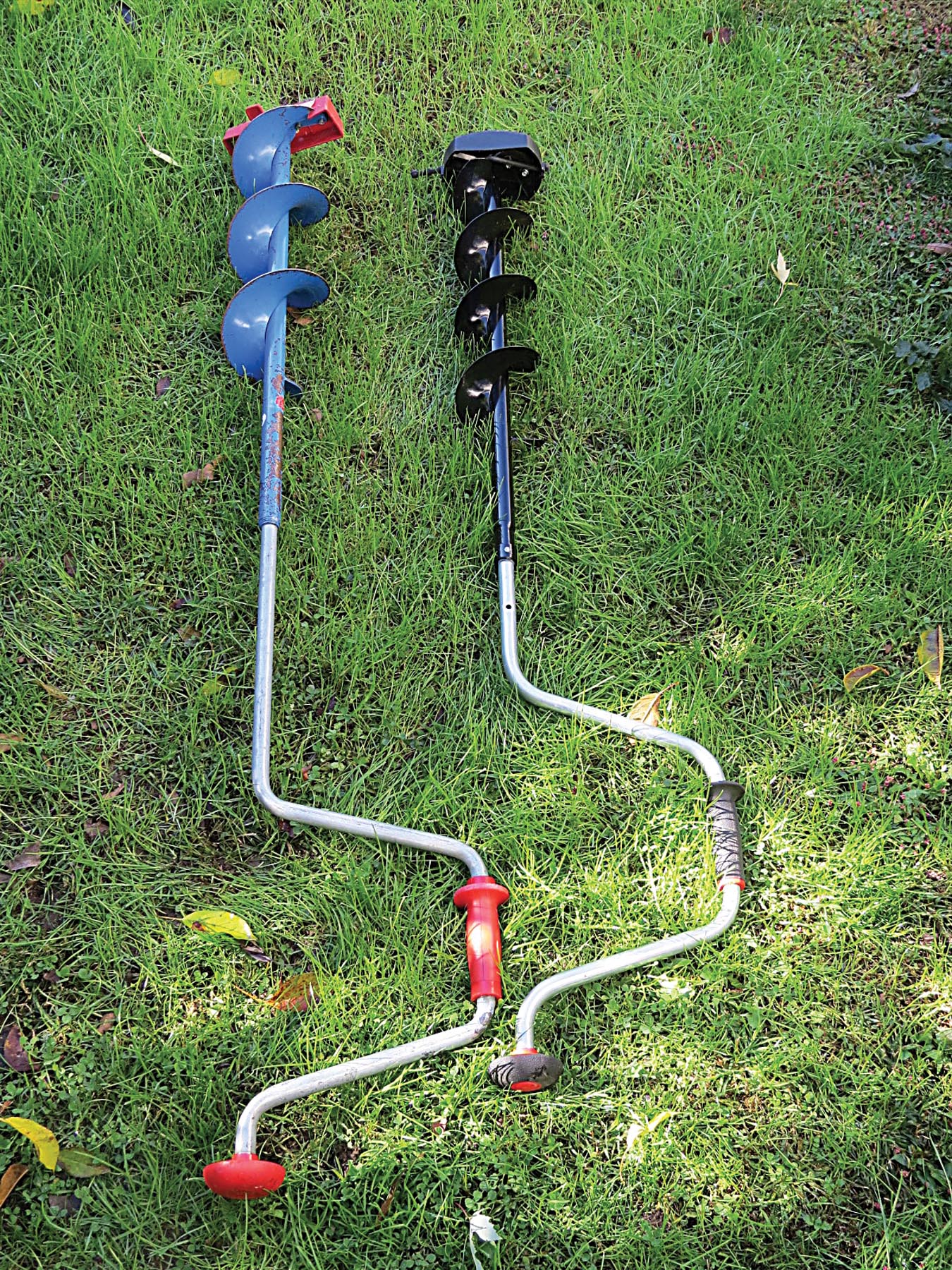

I’m convinced that fish are sensitive to smells. The last thing I want on my hands when I’m fishing is the intrusive smell of gasoline. I did use a two-cycle gasoline power auger for a time, but that was before the advent of lithium ion batteries. I don’t own a power auger right now, but I fish with people who do. This tool cuts a good many holes on one charge and leaves no fish-deterring scent on your hands or gear. But do you really need a power auger? If the ice routinely gets to be 18 inches or thicker where you live, I’d say it’s nice to have. It’s also nice to have if you have physical limitations. But a good sharp corkscrew auger will cut through 12 to 18 inches of ice quite nicely. The key word here is “sharp.”

These stainless steel blades are miserably hard to sharpen; send them in and pay the price they want to put that edge back on. This service is often done by or arranged by the local bait and tackle shop. Fortunately, if you don’t hit a rock these blades do stay sharp for a very long time.

If you just target panfish, use a five-inch auger. If fair sized gamefish frequently enter into the picture, make that a six-inch. There are eight-inch manual augers, but this size hole is unnecessary unless you fish exclusively for very large game fish. If you do, get the power auger.

Although I head out every time with my corkscrew auger, the spud bar or “ice chisel” never stays home. I don’t live in northern Minnesota where people haul out thousand pound (or heavier) ice shanties with their pick-up trucks. Here in southern New York, the ice rarely gets that thick. We have to be more cautious. The spud bar is essential for checking the ice — we poke as we head out on the ice — but it’s also useful for opening up old holes that have skimmed over. In addition, on the most marginal safe ice in early season, it’s the best way of cutting a hole.

Corkscrew augers, the usual ice cutting tools for ice anglers in most regions. Fishermen who live in the coldest areas where the ice gets very thick much more often use power augers.

Fishing line

“Fluorocarbon has changed everything.”

It was a statement that got my attention, given where it came from.

I was in Nova Scotia, bird watching and gathering information for a series of articles. I’d learned that the season was on for giant bluefin tuna, so I’d gone down to some docks on the chance I might get to see one of these fish coming in on a boat. As it turned out, a commercial angler had come in just a short while before, but when I looked down into his boat all I saw was a head — which was impressive enough. The body of the fish had already been put to ice in the facility behind the docks. These fish in the hundreds of pounds headed for the sushi market fetch jaw-dropping prices, well into five figures for a prime fish. I talked to the fisherman.

“Fluorocarbon line has greatly increased success,” he told me. Bluefins have to be one of the largest fish commercially caught on rod and reel (because of stringent regulations) and I guess every advantage helps. Fluorocarbon is about as light refractive as water, meaning that underwater it is nearly invisible to fish. At that time, it was just starting to enter into the consciousness of ice anglers. I’ve been using it since; it works. But it’s more expensive than the monofilament that I’d say the majority of ice anglers still use, and knots are trickier.

In my area, some of the best ice jiggers are Russian immigrants — not surprising considering the climate of their home country. I spy on these fellows at every chance. Some use two-pound-test line for the panfish that they mainly seem to target. I could never acclimate to this light a line as it is so unwieldy and prone to tangling. I use four-pound-test exclusively for winter panfish.

Without any question, day in and day out, the lighter the line you use the more fish you will catch. Of course, if you’re fishing for mixed species that include gamefish, you’ll need to go heavier. Six-pound will cover many situations, except for very toothy fish like pike or pickerel. Some use a steel leader for these species, or at the least, a leader heavier than the main running line, tied in best, I think, with a surgeon’s knot.

Braided line is also of fairly recent advent. I think it’s better suited to open water cast-and-retrieve methods, or some methods involving conventional reels, but I won’t elaborate here.

If you fish deep lakes, monofilament line poses a problem: it’s quite stretchy. For deep water fishing, you might try a heavy Dacron running line of about 45 or 50 pound test. Like braided line, it has very low stretch and it was on all my tip-ups when I fished by that method. (The photo of John and Richie shows an orange tip-up set in a hole. This cool setup is beyond the scope of this article.) The lack of stretch makes it easier to set the hook on a fish that takes your offering down deep, and the thickness of the line makes it easier to handle with cold hands when you’re playing a fish with what is effectively a dropline. Of course, with such a heavy line, you have to tie in a monofilament or fluorocarbon leader to which your bait hook or lure is affixed.

This style of sled with deep sides has become very popular in our area. They come in different lengths; most will accommodate a power auger.

Feeding periods

The single most important factor in your fishing success is fishing where the fish actually are. Since every lake is different, generalizations are suspect if not meaningless. Talk to local anglers to locate the best ice fishing lakes and the best spots on that lake. Some will talk and some won’t. My cousin never stops talking and he’ll tell a stranger who walks up just about everything except how to get a date with his wife. It drives me crazy. Before you know it, he’s friends with the guy and physically taking him to our best spots!

And that leads me to the second most important factor: fishing when the fish are actually feeding. You don’t eat all the time, do you? They don’t either. You can fish until you’re blue in the face but if there’s a “negative bite” on, you may have a wonderful day and then go home and eat hamburgers.

We spend endless hours theorizing about why fish feed so actively one day and then the next day totally turn off. We’re about as close to an answer as we were 30 years ago. Or, as my eloquent cousin likes to say, “Nobody knows nothing about fishing.”

There is no doubt in my mind that some environmental factor plays a role. Is it the gravitational effect of the moon and sun on the earth? The barometer? The amount of sunlight? While science works to figure this out, there is some good advice to offer here.

I’ve already mentioned the negative bite. Few or no fish will be caught during one of these. During a slow bite, fishing will be tough all day long and angling skill will be very important. On these days, bait will greatly outfish the artificial lures that I exclusively use. When a big bite is on, it may seem like anything you drop down the hole works well. So what is the advice? Take advantage of those good days! Cancel appointments and stay out there, as a really good bite doesn’t come along so often. It thus turns out that the master premise in fishing is this: put in your time. Since I don’t think the great days can be predicted, go out as often as possible and eventually you’ll hit one.

Two of the most common and best tasting panfish: white perch, left, and yellow perch.

Having said all that, there a few limbs to climb out onto. We like a calm, cloudy day a half day or so before a strong weather system moves in, usually snow. The tantalizing lull before the storm. We usually do poorly during the storm, although I love being out there for the sheer beauty of it. We think that early morning is generally the best time, though things can pop any time of the day. Without question, in our lakes, white perch are most catchable early morning and late afternoon. Yellow perch are clearly diurnal, apt to bite at any time during daylight hours. I like early to mid morning or sometimes mid to late afternoon for bluegills. Crappies are active night feeders — we’ve gone after them then — and seem to bite least during the middle hours of the day. In actuality, I think the specific characteristics of a lake, including its depth and the amount of weed cover, as well as the type and amount of forage, play a big role in what time of day fish are most active. These can help steer your approaches and methods.

There are exceptions to every fishing rule except this one: if you don’t keep your hooks sharp you will lose half your fish. That’s a promise.

A jigger’s arsenal

I quit bait fishing some 20 years ago, preferring since then to fool them with artificial lures. That being the case, I no longer fish with tip-ups but jig exclusively. I’ll therefore let you find information on bait fishing through other sources and speak only on jigging. I note that all the best ice fishermen I know fish almost exclusively by jigging.

A jig rod is a very short rod of about 20 to 36 inches which is normally used in conjunction with an ultralight spinning reel. In the simplest description, you sit on a bucket and drop your lure to the bottom, reel it up a few feet, then bob it up and down hoping to attract a fish.

There is a whole world of nuance possible in this method of fishing, which explains why two ice anglers sitting next to each other can experience such different results, typically to the exasperation of one of them.

The willingness to experiment is one of the attributes that explains the accurate maxim that 10% of the fishermen catch 90% of the fish. As for jigging, experimentation takes several forms. I’ll list them:

- Choice of lures

- How you embellish or modify the lure

- What action you impart to the lure

- How and whether you work the entire water column

- How you adapt to the intensity of the bite on a given day

- How good you are at detecting very subtle bites

There is room here for just a few specific tips.

Always go forth with at least two fully rigged rods and reels, with a different lure on each. My fishing partners often have four or five jig rods with them. (Check state regulations, however. There may be a limit to how many rods or other fishing devices you can have in your possession at one time.) Carry a wide range of jig lures, and continually try new ones. Make sure they take in a wide range of colors. I like chartreuse and orange best, white second to those. I like a little bit of red on my lures. In deep water, try light-reactive (glow-in-the-dark) finishes that you bring to life with a strong light like a camera flash.

An assortment of ice fishing jigs. The wife of a friend of mine says they look like jewelry.

Left, a plastic tail that gets added on to the hook of an ice jig to add an alluring fluttering action. Center and right, two styles of scent-impregnated plastic baits. These are not gimmicks — they catch fish.

Have a good range of sizes. Larger panfish and even large gamefish will take even the smallest jig lures, but small fish, like bluegills, will be caught most frequently with the smaller jigs.

I’m convinced that one of the best things you can do is add something that flutters on the end of the lure, no matter what you’re fishing for. I use artificially-scented baits sold under various names. These come in many forms and colors and some are thin and fine enough to create that fluttering effect. There are also what some call simply “plastics,” little plastic wiggly things that you simply stick onto the end of the lure’s hooks. Both the scented artificial tag-ons and the plastics help you catch more fish, especially during a slow bite, and especially if you eschew natural bait.

I’m committed to fishing without electronics, although I admit that fish finders will help you locate fish in the deeper lakes. Otherwise, experiment by trying all depths in the water column. That said, unless you’re on a known hotspot, or are fishing with a guide who knows the lake, I think you should stick to shallow water in winter — doubly good advice for panfish. My direct observation is that most anglers who fish deep water in winter have a good day drinking beer and telling stories, but wind up eating out of the local delicatessen. Shallow is much, much easier in winter, when you can’t troll or cast to cover a lot of water.

A friend of mine took an open-water-type spinning lure and cut the blade in half, which causes it to react differently in the water. It’s turned out to be a good fish catcher for us. You can modify lures in all kinds of ways to create different effects, and I encourage you to do so.

Simple recipes for winter panfish

As already stated, the panfish from the waters we fish in winter are white-fleshed and nearly always sweet and mild. I think they are best served by a simple treatment and that is what I almost always give them.

John Zelyez, left, and Richie Norris with a nice bunch of crappies from a local lake.

Breaded filets

Probably half the time I use the tried and true flour, egg, and bread crumb method. Blot the fillets (we always fillet these panfish) nearly dry then dredge them in flour that has been seasoned with salt and pepper and whatever other spices or herbs you like. You then dip the fillets in beaten egg, allowing to drip off all the egg that will drip off. You then immediately press them into bread crumbs on both sides. Let the coating set for a short spell, then sauté in a little butter or else bake them. These can be served with just a little tartar sauce and a squeeze of lemon.

Yellow perch are top shelf eating. Since the fillets from them are long and fairly thin, they can make nice finger food to serve as an appetizer when company comes. Arrange the breaded and cooked fillets on a decorative plate, and place a small bowl of cocktail sauce in the middle — just as you would with shrimp.

Fish sandwiches

These breaded fillets open up other possibilities. For a more filling meal, make a sandwich of them. For this, I like a good, dense white bread. Spread a little mayonnaise on the bread or try this: mash together a little each of mayonnaise and ripe avocado. Add a touch of Dijon mustard and few drops of Tabasco sauce, and use this to moisten and flavorize your sandwich. Lately, I’ve grown fond of fish sandwiches with curry mayonnaise. All you do is add a little curry powder to the mayonnaise and slather it on the bread. I think every fillet sandwich cries out for a piece of crisp lettuce on top, and pickles on the side. I can’t think of a better lunch.

Baked fish

On my mother’s tattered file card it says “Super Baked Fish a la Ann.” Our hometown friend Ann Fenton gave her this recipe and we’ve used it many times. Mix together three tablespoons of mayonnaise, one tablespoon of lemon juice, and one-fourth teaspoon of onion salt. Spread on your fillets. Sprinkle on fine bread crumbs and paprika and bake.

Fish stock

It turns out that the carcasses of these non-oily panfish are superb for stock making, as are those of pickerel and pike. Remove from the filleted carcass the innards, the gills, and every speck of blood. Cut into three pieces each. Place about two pounds of these in a stainless steel pot and add 4½ cups of water, 1½ cups of dry white wine, a few crushed peppercorns, some celery leaves, a few sprigs of parsley, and a teaspoon of fennel seeds. That master chef James Beard tossed in a small onion studded with two whole cloves. The above is his formula slightly modified. Bring the stock to a simmer and simmer just 30 minutes, skimming the foam a few times. Pass through a strainer and then through layers of cheesecloth until the stock is nearly clear. Freeze for future use in making chowder.

My Favorite Things

By Jim Capossela

Raindrops on rose hips, and

Blue elderberries,

Foraging’s fun but it’s

Not what I cherish.

My season’s coming,

There’s frost in the air,

Out with the tackle

There’s no time to spare …

Augers and ice spuds, and

Jig rods so wispy,

Old bait that’s dried, now

It smells and is crispy.

Pine boughs on door hooks, yes

Christmas is near,

First ice is forming of

That I’ve no fear …

When the tick bites —

When the bee stings —

When I’m feeling sad.

I simply remember my

Favorite things,

And then I don’t feel so bad.

Snowflakes on door steps, and

Ice in the cat dish,

Off to the lake cause the

First ice is best fish,

Christmas is over,

Now my holiday,

Butt on a bucket

Without more delay …

Silver white perches,

And green-colored basses,

Crappies with patterns,

That look like eyelashes.

Walleyes that melt into

My sauce meunière,

Well below freezing,

But nary a care —

When the chub bites —

And the trout don’t —

When the tangles are bad.

I simply remember my

Favorite things,

And then I don’t feel so sad.

Coffee is steaming,

And lunch is for sharing,

Cook stove is humming,

And flags up in the air,

Line that is tight

With a fish on the end,

Jig rod with bright lure

Now in a big bend …

You run for that flag,

And I’ll run for this one,

Kids are out skating, now

That looks like real fun.

Businessmen back in

The office today,

Here’s what they’re missing

Well, have a nice day —

When the squall comes —

And the holes freeze —

And the wind rushes by,

I simply remember my

Favorite things,

And then I won’t need to cry.

Ladies in parkas, and

Warm woolen mittens,

Out with their hubbies, I

Guess they’ve been smitten,

Snow geese above us,

Head south on the wing,

It’s hard to describe

Such a beautiful thing …

Warm front is creeping,

And ice turning foggy,

Johhny’s just fallen, and

Boy he looks soggy,

Fingers like carrots,

And chattering teeth,

I’ve had enough till the

New day I’ll greet —

On the big lake —

‘Neath the gray sky —

With my friends all around.

I’ll simply be doing my

Favorite thing,

And never be feeling down.